Why video evidence should not be the only thing that forces the Biya regime to investigate human rights violations

On July 12, Amnesty International released a detailed analysis in response to the emergence on the internet of a video depicting the execution of two women and very young children by Cameroonian armed forces. One of the children was killed strapped to a woman’s back, each executed by the same deadly hail of bullets.

The horror depicted in the recordings hit the international headlines, and the government immediately replied, dismissing the video as “fake” and designed to “tarnish the image of Cameroon’s defense forces.” Eventually, the government promised to look into the video and reported later on having arrested seven soldiers in connection with the event.

Less than a month later, another video came to the attention of Amnesty researchers, this one depicting a “kamikaze” reprisal mission, as jokingly described in the recording by one of the soldiers. The video documents the movement of soldiers on foot and vehicles through a village. Midway through the recording, with structures burning in the background, we witness the execution of a dozen people, sitting and laying against an exterior wall.

Then too, Amnesty released a statement condemning the executions carried out by Cameroonian armed forces. This time, rather than immediately dismissing the newly emerged video as fake, the Minister of Communications said the government would open an investigation, though at the same time claiming the government was facing a “campaign of denigration.”

As human rights investigators increasingly handle video and photographic evidence in the course of their work, the methods used to authenticate the “who, what, where, and when” of these materials have become more and more sophisticated. This authentication work is crucial as it is not uncommon for video or other material to be “fake” — staged, manipulated, edited or — quite frequently — from somewhere else.

Sometimes, it is material misattributed from another place or time. Or it may be a piece of content may show something, but whether it is evidence of a human rights abuse is ambiguous. Like other types of evidence, video and photographic material whose origin or history is unclear is treated with the rightful skepticism by investigators, precisely because misinformation is increasingly manifesting in visual form.

How we authenticated

In the case of the two recent Cameroon videos, the “what” is undeniable — the unambiguous executions of unarmed men, women, and children.

As to who the perpetrators are in the videos. Amnesty International investigators visually identified uniforms, weapons, other equipment, and military ranks, and were all known to be associated with, or belong to, Cameroonian security forces. In one of the videos, identification of the Zastava M21, an automatic rifle that is rare in Africa but used by a small section of the Cameroonian army, was an important clue. Analysis of the audio dialogue — accents and local languages spoken — was consistent with visual findings, and there can be little doubt that in both videos, the Cameroonian security forces were direct participants in the crimes recorded.

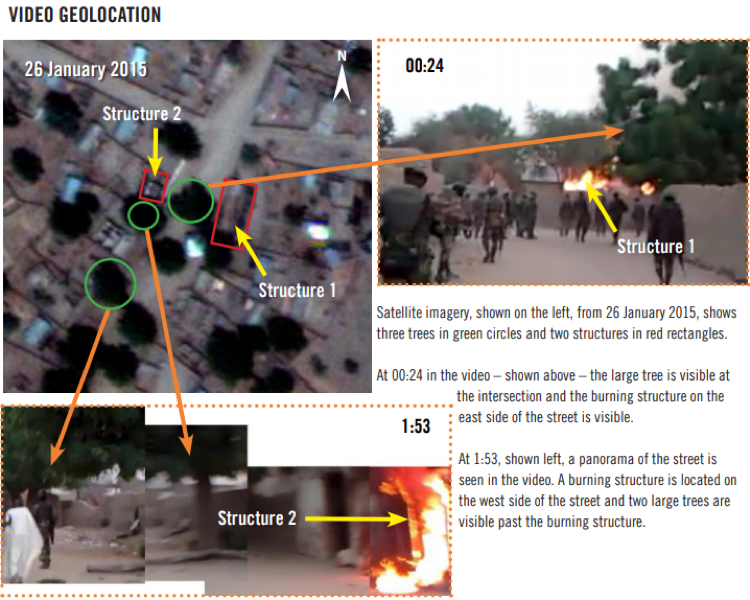

As to when and where the videos were taken, it is more generally difficult to conclude either with certainty without some knowledge of the other. In the case of the most recently released video, investigators identified possible locations through verbal cues in the recording and review by local contacts. Importantly for corroboration, the person recording the video walked for some distance while filming. This allowed analysts to identify many visual cues in the video — road intersections, oddly shaped buildings, trees, among others — as well as their spatial relation to each other.

Analysts at Bellingcat — a collective of online investigators using open source and social media — also working to locate the video — identified a possible location: the village of Achigachia. To independently verify the location, Amnesty investigators took the visual cues taken from the video and plotted against satellite imagery of Achigachia to determine if there was a perfect overlap. There was, including at the exact coordinates in the village where at least 12 people were executed against a wall by a barrage of automatic gunfire. In a longer version of the same video, which surfaced later, the soldiers themselves named the village where the events occurred.

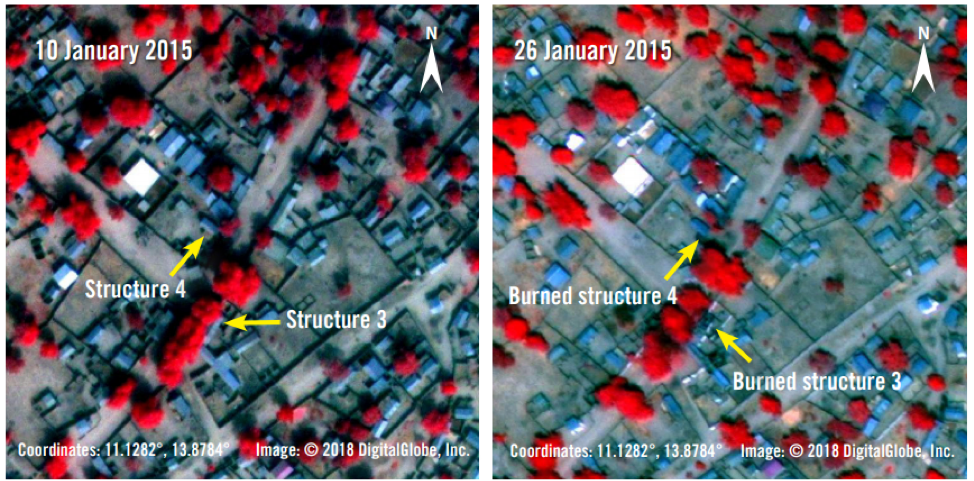

With the confirmation of where the executions took place, the question became whether we could narrow the time in which the crime occurred. With no references to the date, season, or even the year in the video or audio, investigators again relied on satellite imagery. Since the “kamikaze” mission documented in the video included the burning of buildings, an Amnesty satellite imagery expert scanned imagery archives of the town to determine whether burning was evident at those precise points. With luck, two images taken close in time to each other in January 2015 captured the town before fires, and after.

Thus, through careful and detailed analysis, we concluded that the second video was taken in Achigaya between 10 and 26 January 2015 and depicts extrajudicial executions at the hands of Cameroonian security forces.

Why the videos should not have mattered more than previous violations

In today’s media-saturated world, one of the most notable characteristics about these recordings — aside from the uniquely horrifying events they document — is when they were captured. These videos did not capture breaking events. They are both years old.

In response to the video of the execution of the women and children, the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights stated:

“The government of Cameroon has an obligation to investigate this atrocious crime urgently…I am deeply worried that these killings captured on camera may not be isolated cases.”

Indeed, they are not isolated cases, and in most respects, the videos do not reveal an unknown pattern. In September 2015 and again in July 2016, Amnesty issued extensive reports documenting widespread abuses by Cameroon’s security forces in the course of their fight against Boko Haram: arbitrary detention, torture, disappearances, and the killing of civilians.

Over the last 2 years, Amnesty has continued documenting abuses amounting to war crimes by the Cameroonian security forces operating in the Far North and elsewhere. Just as the crimes depicted in the videos are unambiguous, so too are the crimes documented by Amnesty and others over the intervening years since they were first recorded.

While it is not uncommon for additional evidence to emerge after a report publication, this instance is notable because of the attention received in news media, likely a result of the abject cruelty the videos depict. While the government has made initial statements at least paying lip-service to accountability, it should not come only in response to the emergence of video, 3 years after the fact.

While video evidence can be a powerful tool for human rights defenders, and digital connectivity is empowering ever-larger segments of humanity to document the struggles they face, there is a risk. Video documentation cannot become the minimum evidentiary standard that compels governments and authorities to act in the face of abuses by police or security forces.

The absence of a meaningful response by authorities to these horrific acts is part of a larger pattern of unwillingness or inability to hold the perpetrators to account in Cameroon’s fight against Boko Haram. Such an atmosphere of impunity causes the horrific acts witnessed on the videos and documented in extensive reporting. And it leads to equally horrific acts that are not captured in video and will never similarly capture the attention of news media and the broader public.

Scott Edwards is a Senior Crisis Adviser at Amnesty International based in Washington DC.