Who hijacked the World Health Organisation and can it impact the Covid-19 whodunnit?

Taiwan’s exclusion from this week’s annual meeting of the World Health Organization’s governing body highlighted China’s power grab of multilateral institutions. But with Beijing’s renewed commitment to the UN health agency and US President Donald Trump’s funding cut, is an international probe likely to reveal the mishaps and cover-ups of the Covid-19 pandemic?

In early April, as much of the world was under some form of Covid-19 lockdown, the head of the World Health Organization (WHO) veered into uncharacteristically personal terrain during a video press conference.

The detour sparked a diplomatic dust-up, exposed the power machinations undermining the UN health agency and rekindled questions over how a viral outbreak in a central Chinese city spiraled into a global pandemic that has killed more than 310,000 people and brought the world to its knees.

Asked about the criticisms he faced from world leaders such as US President Donald Trump, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus – or Tedros as he’s widely known – replied that he was targeted with racist abuse and even death threats online.

“I can tell you of personal attacks that have been going on for more than two or three months, abuses or racist comments, calling me names; black or negro,” began the former Ethiopian health and foreign minister. But the WHO’s first African director-general did not stop there. “This attack came from Taiwan,” he revealed. “I will be straight today. From Taiwan. Taiwan, the foreign ministry also, knew the campaign. They didn’t disassociate themselves.”

The reaction from Taiwan was swift and damning: Taipei protested, looked into the allegations and traced the malicious posts to China-based email and social media accounts.

China’s misinformation campaigns and aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy have come under international scrutiny during the Covid-19 crisis.

But for Taiwan – a democratically self-governed island that has been a thorn in China’s eastern side since 1950 – it’s nothing new.

The decades-old information warfare along the Taiwan Strait turned particularly virulent after the 2016 election of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who opposes unification with the mainland. Beijing views the island with its 23 million-strong populace as a renegade province under its One-China principle and threatens military action against a separatist Taiwan.

It’s a diplomatically fraught terrain that envoys, certainly former foreign ministers, typically handle with extreme care. But that was not the case with the WHO chief.

“Tedros didn’t check his sources, he reacted to fake news. For someone with such a high level position, he should have been more careful. It was counterproductive, it was proved to have come from China – and when that was revealed, he didn’t react to the news,” said Dorian Malovic, Asia editor of French daily La Croix, and author of several books on China, in an interview with FRANCE 24.

The faux pas exposed critical issues confronting a world mired in a Covid-19 blame game and reliant on multinational institutions to uncover the truth and ensure the future of global health security.

Since the crisis erupted, Tedros has not shied away from upbraiding countries for their inadequate responses. But China routinely receives high praise from the WHO chief for its “commitment to transparency” and for setting “a new standard” in public health.

Beijing’s failure to contain the disease within its borders, or at least limit its spread – unlike recent outbreaks such as Ebola, SARS or MERS – never merits censure.

WHO, what, where on Taiwan

The discrepancy was on display this week when Tedros failed to invite Taiwan to participate as an observer in one of the most important public health meetings of the post-War era.

Despite a US-led campaign that included several European and Asian regional powers calling for Taiwan’s inclusion, Taipei was not represented at the May 18-19 virtual assembly of the WHO’s decision-making body, the World Health Association (WHA).

China, which considers democratically-ruled Taiwan its own with no right to attend international bodies as a sovereign state, objected to Taipei’s participation unless it accepted it was part of China, which the Taiwanese government refused.

Taiwan has participated in the WHA in the past, including as an invited observer from 2009 to 2016, before tensions between Beijing and Taipei peaked in the aftermath of Tsai’s election.

While the WHA Rules of Procedure gives the WHO director-general the right to invite states “to send observers to sessions of the Health Assembly,” Tedros maintained Taiwan’s participation could only be decided by member states with the consent of “the relevant government” – a reference to Beijing.

The semantic back-and-forth finally ended early Monday, when everyone agreed to kick the can down the road, and Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu announced his government had “accepted the suggestion from our allies and like-minded nations” to put the issue off until later this year.

A ‘foregone conclusion’ with future implications

But it was a noteworthy exclusion because the tiny, contested island lies at the heart of issues that the international community agrees require investigations.

Taipei mounted one of the world’s best responses to the Covid-19 pandemic — sparked, according to Asia experts, by its historic distrust of official information from Beijing. Taiwan also claims the WHO ignored an early warning it sent the UN health agency at the end of December 2019.

Its absence at the WHA virtual meeting effectively exposed the weaknesses of multilateral talk-fests that result in communiques with little or no teeth.

Taiwan’s exclusion from the May 18-19 meeting was “a foregone conclusion”, according to J. Michael Cole, Taipei-based senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a Canadian think tank. “Beijing resents the positive attention Taiwan has been receiving amid Covid-19, and it was clear that it would use its influence upon the WHO to ensure that Taiwan did not receive an invitation to participate as an observer. The failure of a group of influential democracies that had called for Taiwan’s inclusion is a clear sign that the current structure of the WHO and the UN in general is failing to meet current realities. As long as structural problems are not addressed, and as long as China’s influence isn’t reduced accordingly, we will continue to see this kind of unhealthy politicisation,” said Cole in an interview with FRANCE 24.

Jockeying for top UN jobs

China’s muscling in on the UN system has sparked warnings over Beijing blocking activists on human rights forums and advancing its signature Belt and Roads project over other initiatives.

“Through neglect and lack of leadership among Western democracies, authoritarian China has accumulated undue influence at the UN Human Rights Council, the Economic and Social Council and the UN General Assembly, where it has used ‘bloc voting’ among member states to further its antidemocratic agenda,” wrote Cole in a post on the Macdonald-Laurier Institute website.

The power grab gets personified during races for the top jobs in the UN’s specialised agencies, such as the WHO. Chinese nationals today head four of the UN’s 15 specialised agencies: the International Civil Aviation Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Telecommunication Union and the UN Industrial Development Organization.

In the FAO leadership race, the EU united behind a French candidate, but failed to sway the Trump administration from supporting a Georgian contender despite news reports questioning the latter’s suitability for the post. In the end, the Chinese candidate was elected with a thumping majority following media reports that Beijing canceled Cameroon’s $78 million debt in exchange for the withdrawal of a Cameroonian candidate from the race.

Victory for Africa – and China

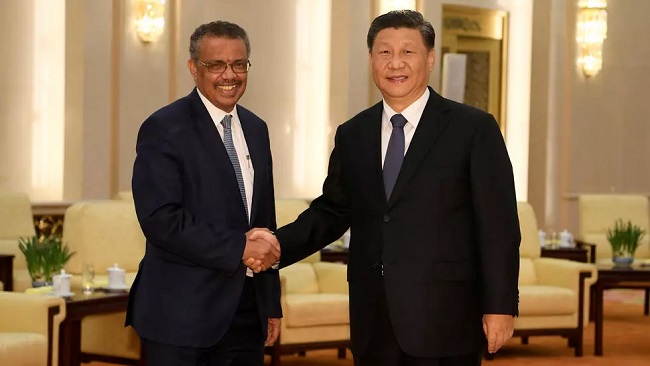

Back in May 2017, when Tedros was elected WHO chief, becoming the first African to lead the organisation, it was hailed as a “victory for Africa”.

A member of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a Marxist-Leninist liberation movement, Tedros is an epidemiologist who trained in the UK before returning home to serve as Ethiopia’s health and later foreign minister. His experience in tackling malaria made him an ideal candidate for the WHO top job.

But it was not without controversy.

The leading candidates in the WHO leadership race were Tedros and veteran British public health expert, David Nabarro. But when Ethiopia’s track record of covering up cholera outbreaks – including under Tedros’s tenure as health minister – came up for scrutiny, supporters of the Ethiopian candidate slammed the “colonial mindset” of his critics.

Lost in the post-colonial slam-fest was Beijing’s vested interest in the race particularly after former WHO chief, Norwegian politician Gro Harlem Brundtland, criticised China for endangering global health by attempting to cover up the 2003 SARS outbreak.

“Tedros was Beijing’s favourite. Prior to his election, he indicated he would abide by the so-called ‘One-China principle’ and he was viewed as more amenable to Beijing’s position onTaiwan than his British rival,” noted Cole.

This year, with the Covid-19 pandemic and a likely focus on vaccine patents and distribution rights, the US managed to forge partnerships with Asian and European democracies to prevent China from exerting undue control over the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

China’s candidate eventually lost to Singapore’s Daren Tang, in early March.

Responding to the US-led campaign for the WIPO post, Beijing slammed the “ugly” interference of the US “hegemon”.

‘Great leap backward’

While there is little doubt that the US, as a superpower, has dominated the post-war global order, experts say the democratic system, including a free and critical press, offers the most effective checks and balances.

The transparency weaknesses of one-party China were exposed by the early cover-ups of the coronavirus outbreak, including the silencing of whistleblowing Chinese doctor, Li Wenliang.

The situation, experts agree, has deteriorated since Chinese President Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012 and has exacerbated since 2018, when Xi effectively became China’s absolute ruler for life.

“Up to 2012, there was confidence that China could join the international community and there was scope for sharing the values of liberal democracy, although none of us were naive,” explained Malovic. “But with Xi Jinping, China has taken a great leap backward in terms of the repression, bullying and coercion.”

The price of access

The effects of Xi’s brand of diplomatic persuasion are at times on display in embarrassing ways.

In early March, when a journalist asked senior WHO official Bruce Aylward about Taiwan’s exclusion from the UN agency, the Canadian epidemiologist’s awkward reaction sparked mirth across the island. Video clips featured GIF birds flying around as Aylward froze in apparent panic, attempted auditory failings, technical glitches, got irritated and succeeded in saying more by leaving things unsaid.

Aylward was of particular interest in Taiwan since he co-led a February WHO mission to China and asserted that if he had Covid-19, he would want to be treated in China, which became another source of Taiwanese jokes.

Cole pins the stonewalling of senior WHO officials on Beijing’s coercion. “The WHO is dealing with a closed, authoritarian regime that treats outbreaks as a national security issue and could cut access to China. It could also make access contingent on certain things, and Taiwan is one of them,” Cole explained. “So, the WHO is ignoring Taiwan for the greater good of access to China. This happens time and again, not just with the WHO, but also with governments and companies – it’s the price of access.”

Access to ‘big’ hotels, meals, speeches

But when China does provide access, Malovic maintains it’s on Beijing’s terms and not always in the interests of the greater good. “These missions don’t really get access,” he said. “They are invited to big hotels, big meals, video conferences where officials speak and speak and speak. The Chinese are masters of manipulating official visits.”

Beijing’s mastery of multinational optics was on full display Monday when President Xi addressed the opening session of the WHA meeting.

Looking calm and statesmanlike, Xi made the headline-grabbing announcement of a $2 billion Chinese contribution “over two years to help with the Covid-19 response and with economic and social development in affected countries, especially developing countries”.

Xi also supported “the idea of a comprehensive review of the global response to Covid-19 after it is brought under control to sum up experience and address deficiencies. This work should be based on science and professionalism, led by the WHO and conducted in an objective and impartial manner,” he said.

Parsing through Xi’s text, Malovic was not impressed. “It’s the typical illusion of well wishing, helping China,” he dismissed. “Let’s get it straight. The review will be on the way countries have managed the Covid-19 crisis and nothing to do with an independent inquiry on the origin of the virus or China’s early handling of the outbreak. The $2 billion is over two years to help with the Covid-19 response in affected, particularly developing countries. I can’t see any help from China to developing countries without the usual take-backs of bank loans, contracts, which is what China always does to put money in countries where they need UN votes.”

What Xi did accomplish, Malovic noted, was “filling the emptiness of the US absence on the world stage” with China’s $2 billion offer contrasting sharply with Trump’s suspension of US funding to the WHO.

As China turns into a campaign issue for Trump ahead of the November US presidential election, the solutions necessary to tackle the WHO’s problems are likely to get blurred. These include Taiwan’s participation in the UN agency and its potential contribution to the global quest for effective responses to public health crises in the future.

The latest WHA meeting concluded with the WHO declaring it would launch an independent review of its response to the coronavirus pandemic. But with Trump responding with funding cuts and “puppet of China” taunts instead of engaging with the UN agency, Beijing, with its additional funding and hefty say on how international investigations are conducted, looks set to increase its multinational sway.

Culled from France 24