China issued no press release, and the Cameroon government did not mention the debt cancellation in its write-up of Yang’s visit.

It was only when a Chinese news report later alleged that Beijing had written off 3 trillion Central African CFA francs ($5.2 billion) of Cameroon’s debt during Yang’s trip that the existence of a deal emerged.

The figure was incorrect. Five billion dollars is close to the amount Cameroon has borrowed from Beijing since 2000, according to the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI), and exceeds the amount the country is believed to still owe.

But while the news report was wrong, its release did force the Chinese government to speak publicly about what type of deal had been reached.

Last week, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying told CNN: “China agreed to waive the interest-free inter-governmental debt that Cameroon had not paid back by the end of 2018.”

That debt was worth $78.4 million. Cameroon’s total debt is 5.8 trillion Central African CFA francs ($10 billion), about a third of which is owed to China, according to the International Monetary Fund.

In short, this was a tiny slice of Cameroon’s liability to China.

So why the initial secrecy?

African debt backlash

Debt write-offs for developing nations are usually greeted with great fanfare, such as the IMF and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, or the Paris Club’s landmark debt wipe-out in the early 2000s.

In China, it’s more complicated: African debt has become increasingly controversial at home.

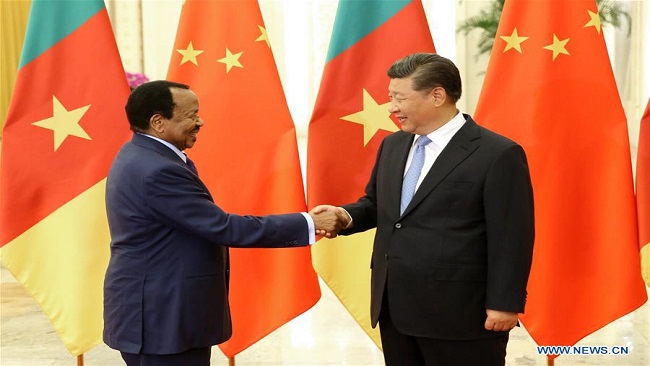

When President Xi Jinping pledged a $60 billion package of aid, investment and loans to Africa last September at the triennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, angry posts emerged on the Chinese internet. Critics questioned why China — where at least 30 million people still live in poverty, defined as an annual income of less than 2,300 yuan (about $340) — was giving money to Africa. Censors quickly deleted the complaints.

There is also this to consider: African nations have borrowed $143 billion from China since 2000, according to CARI figures. Beijing’s leniency toward Cameroon could prompt other heavily leveraged nations, such as Ethiopia, Djibouti and Zambia, to expect similar treatment.

China may have also sought an under-the-radar arrangement because of Cameroon’s political turmoil.

Last week, police arrested Maurice Kamto, the Cameroonian opposition leader who claims to have won last year’s election, along with several staff supporters, amid protests that are fueling political instability.

The West African nation is battling a Boko Haram insurgency in the north, while a secessionist movement is destabilizing the two Anglophone regions of the largely French-speaking nation which was born from the unification of a former British and a former French colony.

Due to the unrest, Cameroon has been stripped of the right to host the 2019 African Cup of Nations, the continent’s biennial soccer championship, which will now take place in Egypt.

From a human rights perspective, the bar for Chinese political partners in Africa is low. Beijing backed Zimbabwe during some of the darkest years of dictator Robert Mugabe’s rule, and poured money into Angola under former president José Eduardo dos Santos, an authoritarian figure associated with large-scale corruption.

But 85-year-old Biya, who has ruled Cameroon for 36 years, is increasingly looking like an “inappropriate partner” from a business standpoint as China faces growing scrutiny on the continent, says Chris Roberts, a political scientist at the University of Calgary.

“Cameroon in every way, shape or form is getting worse by the day in every metric,” says Roberts. “This regime has dismantled whatever foundations it had for a stable economy.”

Deep pockets, deep port

China established diplomatic relations with Cameroon in 1971. Their economic partnership grew after Nicolas Sarkozy became president of France in 2007 and oversaw his country’s decreased engagement with its former colonial territory, leaving a vacuum for Beijing to fill.

Since the turn of the century, China has been granting Cameroon debt relief: In 2001, it canceled $34 million of debt, then in 2007 it forgave another $32 million and $30 million was wiped out in 2010.

Those figures in fact paled in comparison with the $227 million Canada forgave in 2006, for example, notes Roberts.

But it was in 2011 that China really committed to Cameroon by agreeing to build and finance a new port in the fishing town of Kribi. It seemed a stable place to invest: Cameroon was considered a relatively peaceful nation in a war-torn region.

Cameroon’s existing port of Douala was overworked, run down and restricted by its location on a sediment-filled estuary. When completed in 2035, Kribi will be the biggest deep-water port in the region. It will handle exports of Cameroon’s bauxite, iron ore and other minerals and could also serve the Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project, which pumps oil from landlocked Chad.

The first two stages of the project, constructed by China Harbor Engineering Company, were worth $1.2 billion. CHEC is also building a $436 million highway to connect the new port with Douala and has agreed to construct a railway to an iron ore deposit. Other Chinese companies have been throwing up concrete towers around Kribi, in anticipation of its transformation into a thriving regional commercial hub.

The Kribi port will also extend the reach in West Africa of China’s Maritime Silk Road, an initiative that Senegal signed on to last year. It is an important part of President Xi’s massive multinational One Belt One Road economic development plan.

The old port compared with the new Chinese-built facility.

“The Gulf of Guinea is strategic for China,” says Xavier Auregan, a specialist on China-Africa relations in Francophone nations, explaining that a foothold there strengthens its interests in West Africa from the Ivory Coast to Gabon.

“Cameroon is one of the countries that can bring together the energy infrastructure of … West Africa.”

China’s activity in Cameroon is not restricted to the new port: It was responsible for 90% of road construction and restoration in the country as of 2014, and Chinese companies have built dams and hydroelectric power facilities there.

China has also undoubtedly benefited from these developments, with many of the contracts going to its firms.

But the Cameroonian government has taken out considerable loans to fund them and debt repayments look increasingly problematic in a now faltering economy.

“If you’re saying we lent this money for this project or development effort, and we’re just writing it off because we know we’re never going to get it back,” says Roberts, “that has a domestic effect, but it also has international implications.”

One of the big concerns around Chinese loans in Africa is debt-trap diplomacy — the idea that Beijing will pressure countries that can’t repay loans into handing over key assets.

Last December, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta denied that Mombasa’s massive Kilindini Harbor, the largest port in East Africa, had been listed as collateral for a multibillion-dollar Chinese loan to fund a railway. China also denied the report. In Djibouti, similar concerns have been raised over China’s recent acquisition of a stake in a port there.

Gold mine tensions

China’s decision to provide Cameroon with debt relief also comes at a fraught moment between the country’s traditional gold-mining community and Chinese mining companies.

East Cameroon is rich in gold. Justin Kamga, coordinator of the Forests and Rural Development Association (FODER) in Yaounde, says Chinese companies are operating illegal mines across the region and have scant respect for the land.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not reply to CNN’s request for comment.

Local Cameroonian miners typically use artisanal mining methods which do not damage the environment, says Kamga. Chinese companies use heavy machinery that often pockmarks villages with multiple holes 30 meters deep, destroying farmland.

Between 2012 and 2015, Kamga said that more than 250 excavations were abandoned, mostly by Chinese companies. From 2015 to 2018, he said, more than 100 people died in such holes, which trigger landslides and spark local outrage at Chinese companies. In December, nine people died in such an incident, according to FODER.

Regulations stipulate that operators should safely cover holes, but Kamga says the Cameroon army protects Chinese mining companies, meaning they often face little legal retribution. Cameroon ranked 152 out of 180 countries on the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The Cameroon government did not respond to CNN’s emails asking for comment.

Auregan says that while reckless mining has tarnished China’s image, it is unlikely to be the reason for the write-off of the 2018 debt.

“China sees the geostrategic and long-term vision of the importance of Cameroon in that region,” says Roberts.

In short, as long as China needs a maritime foothold in West Africa, Cameroon’s debt burden may be lightened for a while longer.