UK to loan back Ghana’s looted ‘crown jewels’

Mr Hunt said when museums hold “objects with origins in war and looting in military campaigns, we have a responsibility to the countries of origin to think about how we can share those more fairly today.

“It doesn’t seem to me that all of our museums will fall down if we build up these kind of partnerships and exchanges.”

However, Mr Hunt insisted the new cultural partnership “is not restitution by the back door” – meaning it is not a way to return permanent ownership back to Ghana.

The three-year loan agreements, with an option to extend for a further three years, are not with the Ghanaian government but with Otumfo Osei Tutu II – the current Asante king known as the Asantehene – who attended the Coronation of King Charles last year.

The Asantehene still holds an influential ceremonial role, although his kingdom is now part of Ghana’s modern democracy.

The items will go on display at the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the capital of the Asante region, to celebrate the Asantehene’s silver jubilee.

The Asante gold artefacts are the ultimate symbol of the Asante royal government and are believed to be invested with the spirits of former Asante kings.

They have an importance to Ghana comparable to the Benin Bronzes – thousands of sculptures and plaques looted by Britain from the palace of the Kingdom of Benin, in modern-day southern Nigeria. Nigeria has been calling for their return for decades.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, special adviser to Ghana’s culture minister, told the BBC: “They’re not just objects, they have spiritual importance as well. They are part of the soul of the nation. It’s pieces of ourselves returning.”

She said the loan was “a good starting point” on the anniversary of the looting and “a sign of some kind of healing and commemoration for the violence that happened”.

UK museums hold many more items taken from Ghana, including a gold trophy head that is among the most famous pieces of Asante regalia.

The Asante built what was once one of the most powerful and formidable states in west Africa, trading in, among others, gold, textiles and enslaved people.

The kingdom was famed for its military might and wealth. Even now, when the Asantehene shakes hands on official occasions, he can be so weighed down with heavy gold bracelets that he sometimes has an aide whose job is to support his arm.

Europeans were attracted to what they later named the Gold Coast by the stories of African wealth and Britain fought repeated battles with the Asante in the 19th Century.

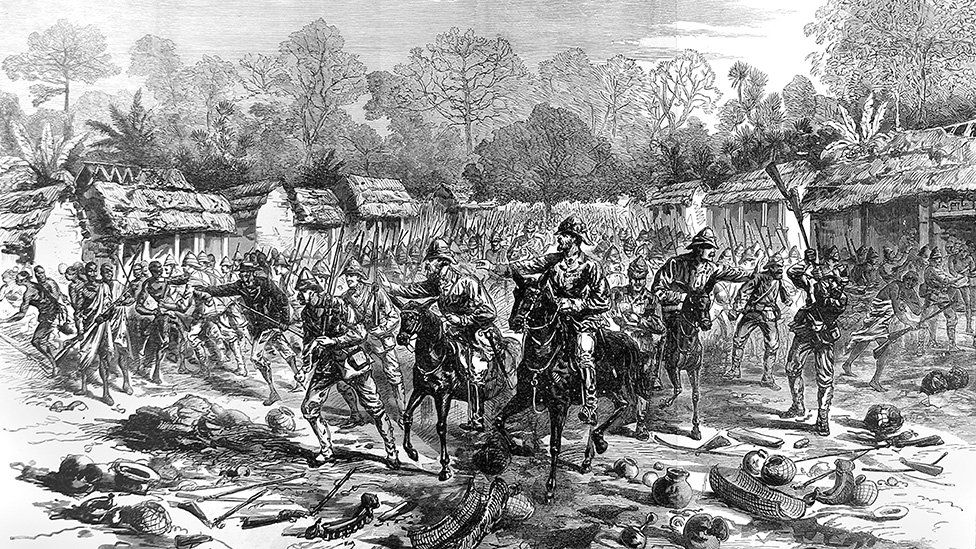

In 1874 after an Asante attack, British troops launched a “punitive expedition”, in the colonial language of the time, ransacking Kumasi and taking many of the palace treasures.

Most of the items the V&A is returning were bought at an auction on 18 April 1874 at Garrards, the London jewellers who maintain the UK’s Crown Jewels.

They include three heavy cast-gold items known as soul washers’ badges (Akrafokonmu), which were worn around the necks of high ranking officials at court who were responsible for cleansing the soul of the king.

Angus Patterson, a senior curator at the V&A, said taking these items in the 19th Century “was not simply about acquiring wealth, although that is a part of it. It’s also about removing the symbols of government or the symbols of authority. It’s a very political act”.

The British Museum is also returning on loan a total of 15 items, some of them looted during a later conflict in 1895-96, including a sword of state known as the Mpomponsuo.

There is also a ceremonial cap, known as a Denkyemke, richly decorated with gold ornaments. It was worn by senior courtiers at coronations and other major festivals.

The British Museum is also lending a cast-gold model lute-harp (Sankuo), which was not looted, to highlight its almost 200-year-old connection with the Asantehenes.

The sankuo was presented to the British writer and diplomat Thomas Bowdich in 1817, who said it was intended as a gift from the Asantehene to the museum to demonstrate the wealth and status of the Asante nation.

‘Cut through the politics’

Can you loan objects back to a country that says you stole them?

It’s a solution to UK legal restrictions that may not be acceptable to countries which say they want to right a historic wrong.

The issue of the Parthenon Sculptures, or Elgin Marbles as they were named in the UK, is the best-known example.

Greece has long demanded the return of these classical sculptures that are displayed in the British Museum. Its chair of trustees, George Osborne, recently said that he was looking for a “practical, pragmatic and rational way forward” and was exploring a partnership that, in essence, puts the question of who actually owns the classical sculptures to one side.

This agreement with the Asantehene is another version of that; a compromise that works for the Asante king and is possible within the parameters of British law.

Just as Nigeria would be unlikely to accept a loan of the Benin Bronzes, it would have been difficult for Ghana’s government to accept this kind of agreement.

But Mr Hunt said the deals between the V&A, the British Museum and the Manhyia Palace Museum “cut through the politics. It doesn’t solve the problem, but it begins the conversation”.

Ms Oforiatta Ayim, the Ghana culture minister’s adviser, said “of course” people will be angry at the idea of a loan and they hoped to see items eventually returned permanently to Ghana.

“We know the objects were stolen in violent circumstances, we know the items belong to the Asante people,” she said.

The British government has a “retain and explain” stance for state-owned institutions, which means contested objects are kept and their context is explained.

Neither the Conservative nor Labour parties have signalled any interest in changing current legislation. The British Museum Act of 1963 and the National Heritage Act of 1983 prevent museum trustees at some high-profile institutions from “deaccessioning” items in their collections.

Mr Hunt is advocating a change in the law. He would like to see “more freedom for museums, but then a kind of backstop, a committee where we would have to appeal if we wanted to restitute items”.

Some have raised concerns this would mean British museums losing some of their most prized items in future. Or as a previous culture secretary, Michelle Donelan, put it to me in relation to a return of the Parthenon Sculptures, that it would “open the gateway to the question of the entire contents of our museums”.

But Mr Hunt said the ownership of very few of the V&A’s collection of 2.8 million items has been disputed.

Another fear is that contested items that go on loan will never be returned.

Ghana’s chief negotiator Ivor Agyeman-Duah scotched that. “You stick to agreements that you have, you don’t go against them,” he said.

There are other beautiful Asante gold items in the UK. The Wallace Collection includes the trophy head which is among the most famous Asante treasures. It too was taken by British forces and bought at the 1874 auction.

The Royal Collection also holds objects including another gold trophy head in the form of a mask. This type of item represented defeated enemies; the trophies were attached by a hoop to ceremonial swords in the state regalia.

Will they ever be on show in Ghana in future? Mr Agyeman-Duah is taking it one step at a time.

But as Britain is increasingly confronting the cultural legacy of its colonial past, these types of agreements may be a diplomatic and practical way to address the past and create better relationships in the future – if both sides can accept the terms.

Culled from the BBC