The War in Southern Cameroons: A Report From Ground Zero

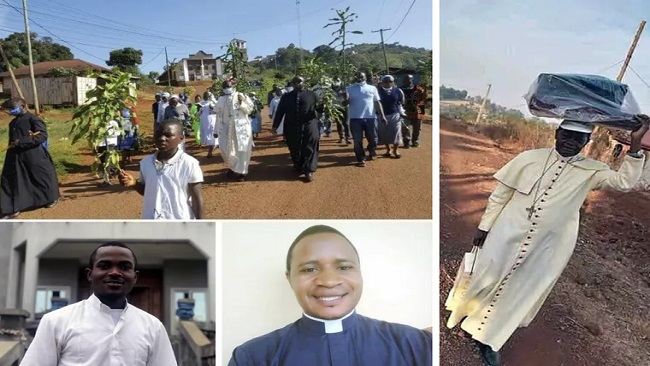

A Cameroon Catholic priest kidnapped on Aug. 29 by separatists was freed two days later in a rare piece of good news in a country suffering from increasing internal conflict that is tearing this nation apart.

Msgr. Julius Agbortoko Abbor, the vicar general of the Diocese of Mamfe, was released after being abducted from the residence of the bishop emeritus of the diocese by a group of young separatists who entered the major seminary compound and kidnapped him, according to ACI Africa.

Just days before the kidnapping, Catholic bishops in Cameroon’s Bamenda Ecclesiastical Province renewed an appeal to end the protracted five-year conflict in the country’s two Anglophone regions in the nation’s northwest and southwest.

“A lot of violence, insecurity, kidnappings, torture, and senseless killings, sometimes of innocent people and children” is continuing in Cameroon, the bishops said, and they appealed to all warring parties to stop the ongoing violence “with immediate effect.”

Cameroon’s internal conflict, which began in 2016 and has worsened since 2018, revolves around marginalization of the Anglophone minority in the country (20% of the population) and its grievances against the majority Francophone population and administration.

Anglophone lawyers had complained in the mid-2010s that the English legal system was being undermined and overwhelmed by the civil law system, dominated by Francophone jurists, lawyers and magistrates. Meanwhile, teachers in the Anglophone part of the country grew resentful that non-English-speaking educators were being sent to teach students in English.

These and other resentments, coupled with inadequate leadership from President Paul Biya, 88, led to a brutal military crackdown by the government in 2017 of peaceful demonstrations. Violence was also perpetrated against lawyers, there were incidents of torture and rape, including of students at the nation’s Anglophone university, along with the arbitrary arrests and detention of peaceful protesters, many of whom remain in prisons around the country.

These injustices led to the growth of of more than 30 Ambazonian militia groups, known locally as “The Boys,” in the historically English-speaking regions. Formed in 2016, they are pushing for a new autonomous region called Ambazonia, covering territory that had been the former British colony of Southern Cameroons, but which became part of unified Cameroon in 1961.

The Ambazonian separatists have since embarked on destroying everything that belongs to the Francophone government — houses, markets and goods, and have killed some of those who fail to respect them and their objectives.

Particularly damaging has been the closure of schools in the two regions since the beginning of the crisis. Only a few of the schools manage to operate, and they are vulnerable to attack at any time, with teachers and principals at risk of death and school buildings set on fire. One was gutted last week just before the start of the new academic year by unidentified persons.

An Ambazonian fighter told the Register he joined the separatist cause, “because of the torment Anglophone citizens have been suffering from La Republic [Francophone] government.”

“I therefore decided to join the fight for independence,” he said. “I have been fighting for over four years now.”

Others told the Register they joined because the army had destroyed their houses, killed family members and committed acts of torture, and so they joined to retaliate.

Humanitarian Crisis

More than 3,500 people have been killed since the current conflict began in 2016 with killings taking place on daily basis, according to humanitarian organizations.

Over 67,000 people have fled across the border and are now living in Nigeria or remain as refugees there. According to a U.N. report, 4.4 million people are threatened by the war, while 2.2 million are directly affected. Thousands have been internally displaced, living in unbearable conditions in other French-speaking regions.

Emmanuel Lampaert, operations coordinator for Doctors without Borders (MSF) in Central Africa, said that many of those in hospital are suffering from malnutrition.

“We cannot stay any longer in a region where we are not allowed to provide care to people here,’’ Lampaert said in reference to the government suspending MSF activities in the region last December after accusing it of supporting the armed groups.

“The suspension significantly reduces access to medical services in an area where communities are badly affected by armed violence,” he said. “Those who have fled the violence often take refuge in the bush, far from any health facilities, vulnerable to malaria, infections or snakebites, in locations often inaccessible for emergency vehicles such as ambulances, or even motorcycles.”

“When two elephants are fighting, the grass suffers” goes the old African saying and it is particularly apropos to this five-year old conflict that has brought great suffering to the local population, caught as it is between the military and secessionist fighters. It also shows no sign of ending, as the government continues to be reluctant to build a general consensus and truthful, inclusive national dialogue with all the protagonists to find a lasting solution.

The Catholic Church has been deeply concerned about the crisis. Christians represent the majority in the region and have been badly affected. The bishops of the Bamenda Ecclesiastical Province wrote a memorandum in 2016 outlining the cause of the conflict and proposing solutions but it received no response from the Biya administration.

The late Cameroonian Cardinal Christian Tumi, who died in April aged 90, tried to convene an all-Anglophone conference but it required government and international support which were not forthcoming. Church leaders, meanwhile, have used their pulpits and give interviews to local TV channels to make their voices heard.

In an interview with a local TV channel on Feb. 24, 2020, Archbishop emeritus Cornelius Fontem Esua of Bamenda — who was once taken hostage by secessionists — said, “The position of the Church is that we are neutral, neither for the government nor the Amba boys. We tell them: no violence, no killings, that God’s law is ‘Thou shall not kill’ whether it’s the military or the Amba boys.” To resolve the conflict, he said there should be a total amnesty: “Let the military go back to their barracks and the Amba boys should put down their arms.”

Without mincing his words, Cardinal Tumi said in 2019 that most of the killings in the regions are by the military because they are the ones with sophisticated weapons. The separatists do kill, but their targets are the military and those whom they suspect are enemies of the Ambazonia, be they Anglophone or Francophone. For example, five police officers were given a state burial last month after being killed by a mine laid by separatists on Aug. 10 in Bafut, in the northwest region.

Last week, 15 soldiers were killed in an ambush by the separatists fighters led by a commander of the Bambalang Marine Forces who calls himself “General No Pity.” Separatists have also recently burned down a market, the office of a local mayor, and the residence of a senior law enforcement officer in Balikumbat, northwestern Cameroon. These acts of violence have even led to some Francophones calling on the army to step up their fight instead of calling for peace.

Many civilians continue to perish regularly. On Aug. 20, a 7-year-old girl, a pupil of St Therese Primary School in Kumbo, was shot and killed in crossfire. Two weeks earlier, seven civilians were killed by the military in Meluf, including local citizen Jude Thaddeus, a nephew of this correspondent.

In July 2018, Mill Hill Missionary Father Alexander Sob Nougi was accidentally killed by a stray bullet on Church premises. In May 2018, many people mistaken as separatists were fatally shot by the military in Pinyin, while what has become known as the Ngarbuh incident, which took place on Feb. 14, 2021, 21 civilians, including 13 children, were killed in their sleep by Cameroon soldiers and Fulani militia, a predominantly Muslim group better known in Cameroon as “Mbororos,” who claim to be victims of separatist groups.

According to a report from Human Rights Watch, 350 people have been kidnapped since October 2018, including 300 students and released after a ransom was paid in most cases. Cardinal Tumi was also kidnapped in 2020, as priests and religious seem to be targets. The report also condemned regular use of torture and secret detention from Cameroon authorities.

Cameroonian Voices

Father Gaston Yuven, a curate of St. Paul’s Parish, Kikaikom Kumbo Diocese, a stronghold of the armed secessionist group, told the Register, “It’s disastrous but this doesn’t stop people going about their daily activities. One just needs to enquire before taking any step. Then you’re safe.”

“There is an increase in faith; more people come to Church,” he added. “Those who want to come always make it but when it is not safe, the liturgies go ahead while the others keep themselves safe. More people turn to put God at the center, but a few seek protection elsewhere.”

“The present situation is getting worse because more casualties are being registered,” Deacon Doh Lawrence of the Diocese of Kumbo said. “Many innocent civilians are killed, and gun battles have intensified. Nearly everything is at a standstill because many roads are blocked, and battles continue. Poverty has increased, people are dying in houses because of no medical attention. Churches are empty because people have been displaced. Many schools remain closed because of threats from separatists, economic activities are experiencing a heavy downturn. Kumbo market is nearly empty since many people can’t sell their goods.”

A separatist fighter told the Register that “right now the situation here is not calm. We have been losing lives here about a week now. A child of 7 years was shot in Kumbo by the military and they’ve also been raping our women, burning down people’s houses, stealing from people’s houses, keeping military bases in villages. The situation is getting worse and worse.”

A military source who spoke on condition of anonymity said a lot of uniformed men have been lost since last month in the two regions, with daily reports of them being killed either during confrontations or setting off mines laid by the separatist. Some reports even mention 3,000 military deaths since the beginning of the crisis, and the number could be higher.

To make matters worse, the blockage of roads is forcing civilians to cover miles on foot to either get to the hospital, markets, etc., since no vehicle is allowed. Bishop George Nkuo of the Kumbo Diocese once had to trek many miles with his Mass kit for his pastoral mission to a neighboring village.

But despite all these difficulties, faith in the region remains robust: thousands of Christians hold firm to the belief that God is the one to bring an end to this war. Thus their unflinching trust in God persists through all the difficulties they are going through.

The unwavering faith of Christians is something to behold — they constantly pray for a return to peace. The pain is great, the damage irreparable. Enough blood has been shed, and human life has lost its value in the troubled regions. There is fear, insecurity looms all over the conflict-torn regions. The end of the war is not a matter of today nor tomorrow. The government vehemently refuses to adhere to numerous proposals, instead offering solutions that are far from bringing an end to the conflict.

A so-called “grand national dialogue” between the warring parties took place Sept. 30 -Oct. 4, 2019, but it seems to have been a place to squander billions rather than to discuss a path to peace, the result being that after the talks, atrocities increased, with the number of killings more than ever, and schools still closed in most areas.

As Archbishop Esua of Bamenda said during his interview, some topics like the form of the state were considered taboo during the national dialogue, which is the major concern of the Anglophones. This has led people to question the seriousness of the government in finding a lasting solution to this problem. The creation of a national disarmament, demobilization and reintegration committee (DDR), the special status of the two English regions, and a special fund for the reconstruction of the two destroyed regions are merely dormant measures that have yielded little fruit because the situation on the ground remains chaotic.

Epilogue: A Correspondent’s Analysis

Speaking as a Cameroonian who has witnessed this conflict first-hand, I can say that never in the history of this nation has it been on such a divided course. People are divided more than united, opinions are opposed, clergy are against clergy, politicians against politicians, Francophones against Anglophones, Anglophones against Anglophones.

Some who are radical want total independence while the majority want a complete federal system of government, separate from the current centralized system of government. But even with decentralization, it still doesn’t answer the wish of the Anglophones.

As division continues while more blood is shed, the majority of government workers — teachers and other public workers — have fled the regions but continue to earn their monthly salary. Some have not taught for the past four years. They are targeted by separatists. The region has gone backwards by 20 years — economically, socially and spiritually. Those areas that have been the most resilient, such as Kumbo, which is one of the biggest and more active parts of the region, has become a shadow of itself.

As long as both sides are unwilling to discuss the issues fairly, a compromise will remain elusive. People are afraid to talk, even some bishops have forbidden their priests from speaking publicly on the issue. Because the truth is hidden by lies, the military and separatists are unable to accept responsibility for the atrocities they commit.

The international community needs to act so these atrocities will stop. Mere words of condemnation are not enough; they need to act. Young people are frustrated, some becoming armed robbers or prostitutes in other towns. Hundreds have joined the separatists because their future has been destroyed by the brutal government. Their homes, businesses, means of transport have been confiscated.

Only God knows the end and how long this will go on. One particularly regrettable fact is that since the beginning, this crisis has never even been considered an important issue in both houses of the parliament, serving to only increase the anger of the oppressed. But another thing is certain: If the damage that has been caused and is still being caused is never redressed, the conflict will only increase hatred between the oppressed and the oppressor.

Source: National Catholic Register