The Southern Cameroons Crisis Demands A Real Dialogue

The Anglophone Crisis has ravaged an area of Cameroon that is home to more than 3.5 million people – approximately a seventh of the country’s population – and yet it remains one of the world’s forgotten conflicts. General strikes and protests beginning in 2016 gave way to a formal declaration of independence the following year, pitting English-speaking separatists against President Paul Biya’s Francophone government in Yaoundé. The situation has deteriorated since, with last month’s parliamentary elections leading to further unrest.

At the start of the year, Mr. Biya promised that the deployment of additional troops to the area would ensure that the vote proceeded as planned. Polls across the Northwest and Southwest regions were indefinitely postponed anyway, even as the military presence remained.

In the English-speaking Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon, teenagers are kidnapped and mutilated by separatist militants who want to discourage them from attending schools. Villages like Ngarbuh are the site of brutal massacres, shows of force orchestrated by government soldiers seeking to dissuade civilians from harbouring dissidents. Candidates for political office risk kidnapping and assaults and more than 80% of schools, and 40% of health centres are closed. Over 3,000 people are dead and more than 700,000 displaced, including 50,000 refugees who have fled across the border to Nigeria. The Cameroonian army’s inability to curb separatist influence and its complicity in atrocities like the attack on Ngarbuh, suggests that higher numbers of boots on the ground will do little to stem the bloodshed.

Cameroon’s linguistic divide and the grievances that it has fostered is rooted in the country’s very foundation. A 1961 referendum led to what is currently Northwest and Southwest Cameroon joining a newly-independent French Cameroon, instead of English-speaking Nigeria to the north despite a history of English rule. The absence of leadership from the British and French governments, whose forerunners laid the groundwork for this powder keg, is a particularly striking failure.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been silent on the matter since a 2018 tweet, back when he was Foreign Minister, which noted an “urgent need to pursue dialogue, decentralisation and respect #humanrights in Anglophone Regions as [Paul Biya] has previously committed.”

French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to exert “maximum pressure” on Mr. Biya to address the Ngarbuh massacre. He quickly adopted a more conciliatory tone. A phone call at the beginning of March succeeded in defusing the resulting tensions between France and Cameroon, but did little to advance prospects of a peaceful resolution to the crisis. Biya’s commitment to an investigation of the massacre following the call was a hollow victory for Macron. Cameroon’s government had already announced it was opening an inquiry and the problems the country faces extend far beyond one act of violence.

Efforts within Cameroon to find a resolution have been more concerted but just as ineffective. The Major National Dialogue, a summit called by Mr. Biya in September and October last year, made for good political theatre. It excluded several major separatist leaders, some of whom were still in government detention. These meetings produced vague commitments for greater Anglophone autonomy. A period of intensified violence immediately followed them in western Cameroon.

Though devolution is a step in the right direction, Mr. Biya’s subsequent efforts to placate the separatists were doomed to fail, due to their limited scope and the lack of consultation. Legislation passed by parliament in December promised “special status” for the Northwest and Southwest regions, granting them their own legislative assemblies and executive government. The bill was pursued by the Biya government unilaterally with little concern for the input of the people it was meant to appease. Moreover, the provisions granted under “special status” are insufficient. Critics describe it as “too little, too late,” noting that many of these autonomous institutions would still depend on Yaoundé to approve their decisions. Amid a crisis where lack of trust in the central government fuels Anglophone resistance, only genuine consultation and good-faith negotiations can remedy the situation.

For that kind of dialogue to happen, French and British absenteeism must end. Mr. Macron, whose country is Cameroon’s closest partner, should follow the lead of President Donald Trump, whose administration last year reduced military assistance and trade concessions to Cameroon in response to its human rights violations. Military and economic influence can be used to corral Mr. Biya into commencing negotiations and the involvement of foreign leaders in the peace process will help ease the doubts of separatist leaders. Several Anglophone groups boycotted the Major National Dialogue due to scepticism about the Cameroonian president’s intentions and lack of international oversight. Meaningful involvement from Messrs Trump, Macron and Johnson would go some way in kick-starting the peace process.

Mr. Biya will need to engage with the broad array of separatist groups claiming to represent English-speaking Cameroonians. There is no point for a peace agreement that excludes some groups, as they will simply continue fighting. Releasing political prisoners and mollifying the concerns of separatist leaders who boycotted last year’s summit is imperative. The separatists, for their part, cannot continue to violently enforce bans on education and political activities if they want to reduce military presence in the west. The government will not entertain reducing its troop deployment – a necessary precursor to fruitful negotiations – if militants continue to deprive the people in the region of education and healthcare access.

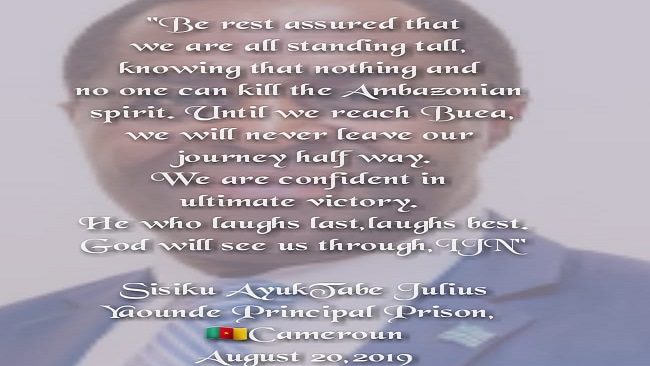

If Mr. Biya and the relevant opposition leaders are able to begin discussions, a successful outcome will depend on significant concessions from both sides. The extreme position of many separatists, an independent Anglophone state called Ambazonia, is untenable and would not be accepted by Mr. Biya or the international community. On the other hand, the response to December’s devolution bill proves that fundamental change is necessary to appease Cameroon’s English-speakers. Returning the country to a federal system (it was shortsightedly transformed into a unitary state in 1972) would preserve ultimate authority in Yaoundé, while still providing those in the Northwest and Southwest with genuine autonomy under a powerful regional government.

Separatists who have styled themselves as leaders of a newly independent state would be disappointed by the devolution of authority. By the same token, it remains questionable whether Mr. Biya would be willing to relinquish control after forty years of accumulating centralised power. The three years of violence and disorder have been bad for Cameroon and its Anglophone regions. Each escalation, troop deployment and human rights violation has merely exacerbated the conflict. This crisis will only end when the relevant parties are willing to make concessions through real dialogue instead of political performance.

Culled from The Organization For World Peace