The First Butcher of Yaounde Seeking Seventh Term

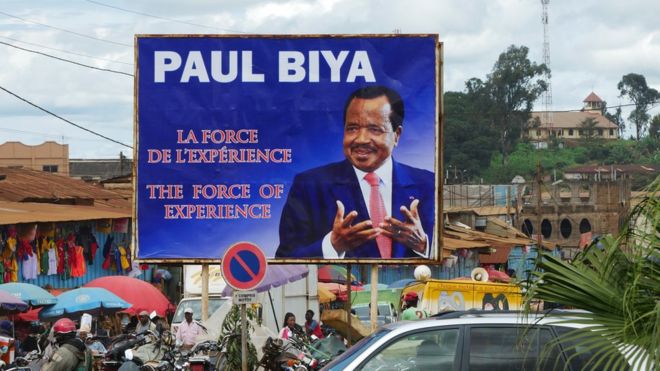

A large poster of President Paul Biya hangs like a street sign in Cameroon’s western city of Bafoussam.

“The force of experience,” reads the poster in reference to President Biya’s 36 years in power, to which he now hopes to add another seven-year term.

A couple of metres from the poster, members of Mr Biya’s governing CPDM party are meeting to drum up support for the person they call their hero.

“Young people may be eloquent. They may make big promises, but none of them can have the steady hands to run a large country like Cameroon,” says party supporter Emmanuel Ndam, 58.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES“For over 30 years, our president has been tested by various crises, and each time, he has been able to overcome,” Mr Ndam adds.

“Just look at the mature way he handled the Bakassi crisis with Nigeria. Some hot-headed youth could just have messed up the situation,” he adds, before making his way into the meeting hall.

His comrade Alice Meye, 22, agrees. She says only President Biya has the wherewithal to resolve Cameroon’s myriad crises, most urgent of which is the unrest in the country’s two English-speaking regions.

“We have a president who does what he promises to do. He has said he will solve the problems of our Anglophone brothers. Let’s give him a chance.”

“Even in death, President Paul Biya will continue to reign,” she said.

‘The old man is tired’

But not everyone believes Mr Biya, Africa’s second-longest serving leader, still has the charisma and the physical stamina to stay at the helm.

Picking out specks of beef from his teeth with a wooden pick, Ibrahima Sadiki, a resident of the capital Yaoundé’s swampy Briqueterie slum tells the BBC “the old man is tired”.

“This is a man who should normally stay quietly in the village, playing with his grandchildren.”

Arguments about the president’s age, however, pale in comparison to the numerous problems Cameroon faces today.

A separatist uprising in the country’s two Anglophone regions – the North-West and South-West – is stretching Cameroon’s much-hyped unity to the limits.

In October 2016, teachers and lawyers in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions took to the streets to protest at the imposition of French in schools and courts.

But those protests soon took a political dimension, with thousands of English speakers taking to the streets on 1 October last year to declare the independence of a new country they called “Ambazonia”.

The government cracked down in response. Hundreds of people have been killed – at least 420 civilians, 175 military and police officers, and an unknown numberof separatist fighters.

More than 300,000 people have also been forced to flee their homes, according to the International Crisis Group.

AFP

AFPIn addition, the economy of the region has been devastated.

The Cameroon Development Corporation – the second-largest employer after the state – has lost 50% of its production, according to its Director General Frankline Njie.

According to the IMF, Cameroon has lost more than 24 billion CFA francs ($42m; £32m) in 2018 alone as a result of the crisis.

Mr Biya’s repeated absences from the country have further riled his critics – the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) estimates that the president spent nearly 60 days out of the country last year on private visits.

Colonial roots – Cameroon’s ongoing divisions:

AFP

AFP- Colonised by Germany in 1884

- British and French troops force Germans to leave in 1916

- Cameroon is split three years later – 80% goes to the French and 20% to the British

- French-run Cameroon becomes independent in 1960

- Following a referendum, the (British) Southern Cameroons join Cameroon, while Northern Cameroons join English-speaking Nigeria

- In 1972, another public vote sees Cameroon dropping its federal form to become a unitary state

- Ever since, many Anglophones have complained that their regions were being neglected and excluded from power

- Today, some militia groups and separatists want an independent state

- Others want a return to the federal system of two states – one English-speaking, the other French-speaking

The fighting has left a trail of destruction and death. In May on a visit to the country’s North-West region, I came face-to-face with the stark reality.

Approaching the regional capital of Bamenda, you have to go through rigorous security controls.

At Santa, a locality that borders the country’s French-speaking West Region, a gun-toting mix of soldiers and police officers tell every passenger to step out of their buses, ID cards in hand.

The next 500 metres or so must be travelled on foot. No chances are taken, because an “Amba boy” (separatist fighter) could be hidden among the passengers.

But as you get out of town and into the villages, there is a sense that the government has lost control.

The armed separatists have vowed to enforce a boycott of the 7 October election, raising fears of attacks on polling stations and a low turn-out in the mainly Anglophone areas.

Control posts are now manned by rag-tag Ambazonia fighters. I came across one such post at Bambalang, some 20km (12 miles) from Bamenda.

“Where is your voter card?” one of them asked me, waving a machete. I didn’t have one because I’d been advised not to carry it on me, lest it be destroyed.

The “Amba Boys” have been confiscating voters’ cards and destroying them.

Voter intimidation

The authorities have taken seriously the separatists’ threat to disrupt the poll.

According to the head of Cameroon’s electoral body Elecam, Erik Essousse, the number of polling stations has been reduced in the north West and South West Regions and others moved from turbulent zones to more secure areas.

But the move has been criticised by the main opposition Social Democratic Front, which says it could disenfranchise voters unable to travel longer distances to the new polling centres.

Despite the uncertainties, the campaign is gaining steam and creating suspense.

“It’s over for Paul Biya,” a supporter of the CRM party’s Maurice Kamto tells the BBC, who then joins thousands of people in a chorus singing “Goodbye Paul Biya, Kamto is coming.”

The sense of optimism is also expressed by Seralphine Neh, 22, who supports the election’s youngest candidate, Cabral Libii.

She sees the 38-year-old career journalist as the embodiment of a new kind of politics – one that is shifting the focus from “a system of gerontocracy, to that of inclusion where the youth feel involved”.

But President Biya’s supporters do not see things that way.

Tatiana Nzana who sells CPDM gadgets in Yaoundé tells the BBC: “We want someone with experience, with wisdom. We don’t want ping-pong players.

“That’s why we will continue to vote for him. Better the devil you know than the angel you don’t know. Even after his death, he will still be president.”

In total, there are nine candidates in Cameroon’s presidential elections. Parliamentary and municipal elections, meanwhile, have been postponed to October 2019 after the presidency and lawmakers cited organisational difficulty

President Biya himself has organised only one rally, in the country’s North Region, where he praised the people for their resilience in the face of Boko Haram attacks.

Security forces have been accused of using excessive force in their attempts to deal with both the Boko Haram insurgency to the north, and the Anglophone crisis to the west.

A BBC investigation into a horrifying viral video which shows Cameroonian soldiers leading away and killing two women and two young children in northern Cameroon was initially dismissed by the government as “fake news”.

But Cameroon’s government has since admitted that it has detained seven soldiers in connection with the killings.

Speaking at his campaign rally in Maroua, President Biya blamed separatists for the Anglophone crisis but seemed to acknowledge their grievances, saying:

“Evidently, we still have to restore peace in our two regions of the North-West and the South-West, overburdened by secessionist exactions”.

Mr Biya spoke of the need to satisfy the “just demands” of the country’s English-speakers in order to demonstrate to them that their future lies in an undivided Cameroon.

He had planned a similar rally in the restive South-West region, but suddenly called it off without further explanation. Observers have said he was wary of the separatist threat.

Joshua Osih, a first-time candidate for the main opposition SDF party, has said he could resolve the problem within 100 days in office. He has made the radical proposal of a return to a federal structure of government.

But it is not only the Anglophone crisis plaguing Cameroon.

The Central African nation also suffers from a crisis of governance, illustrated by its undesirable position in 1998 and 1999 as the world’s most corrupt nation, in Transparency international’s rankings.

One of the presidential challengers, Akere Muna – himself a former executive with the anti-graft body – has pledged, if elected, to focus on the fight against the scourge.

“Cameroon loses 40% of its revenue in corrupt practices. We have too many structures in the fight against corruption,” Mr Muna has said.

“We are going to have one department – consolidated, that will do prevention, investigation, sanctioning, and prosecution and that will also be in charge of the recovery of assets.”

Despite the new faces and the unprecedented challenges, few expect 85-year-old Paul Biya to be rattled in the face of a splintered opposition.

Culled from BBC