The armed kidnapping in Abuja and smuggling out to Yaoundé of 10 prominent refugees and asylum-seekers

Sisiku Julius AyukTabe returns to Nigeria on 3 January 2018 from a visit to the United Kingdom and the United States of America. He invites some close friends for a meeting to discuss a humanitarian initiative initiated by him while abroad and also the crisis that erupted in September 2016 in their homeland, the Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia. That crisis involves the territory of the Southern Cameroons invaded and occupied by the military forces of the Yaoundé regime. The invasion has displaced hundreds of thousands of persons as IDPs and as refugees fleeing into Nigeria and other countries. The meeting is to explore ways and means of handling this endless flow of refugees. The invitation is sent out through Whatsapp. The meeting is scheduled for 5th January 2018. The venue is the NERA Hotel, Alex Ekweme Avenue, Abuja, Nigeria.

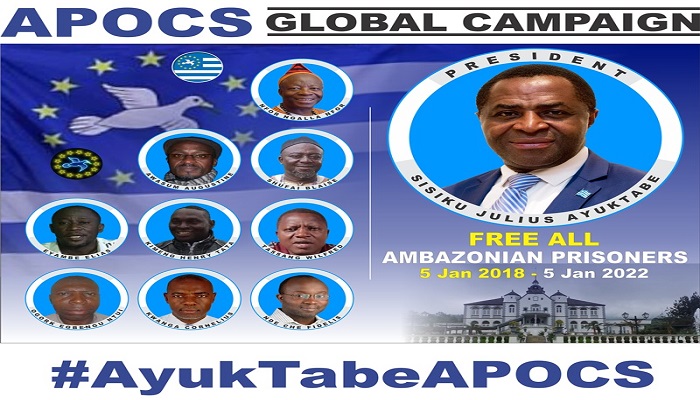

Twelve persons, one lady and eleven gentlemen, honour the invitation and are present at the NERA Hotel for the meeting. They are: Barrister Nalowa Bih, Barrister Shufai Blaise Berinyuy, Dr. Ojong Okongho, Dr. Cornelius Njikimbi Kwanga, Dr. Professor Egbe Ogork Ntui, Mr Nfor Ngala Nfor, Dr. Professor Kimeng Henry, Dr. Professor Augustine Awasum, Dr Fidelis Ndeh-Che, Barrister Eyambe Ebai, and Mr Tassang Wilfred.

The kidnaping

It is about 7:30 pm and the meeting has barely started when there was heard a loud shout: “LIE DOWN! LIE DOWN!” The attendees look up. They notice that the order is coming from about 20 heavily armed and hooded men with automatic guns pointing at the attendees. It is a mixed squad, some in army uniform, some in police uniform, and others in mufti. The attendees are ordered to lie face down. No resistance is offered. The attendees are confused and terrified. They comply with the order. The terror spectacle is taking place in the presence of some five hundred guests of the hotel. There are other hotel guests occupying tables next to those of the attendees. The tension and panic caused by the gunmen forces these other guests to lie down even though the command is not directed at them. The attendees hear people running away and screaming. They are shackled in pairs with their hands to the back. They are marched outside to the front of the hotel entrance. There, they are blindfolded and shoved into four waiting cars.

The four cars are accompanied by others, all driving in a convoy. They go around Abuja at breakneck speed. The kidnappers drive for over an hour and then stop at an isolated location. The drivers step out and discuss for about two hours. The kidnapped persons (hostages) remain blindfolded inside the cars, the windows of which are wound up and the air conditioning turned off. Later, the cars are driven off by a different set of drivers at the wheels. This nocturnal, apparently aimless drive around Abuja, continues for another 30 minutes or so. The hostages are taken to a building later identified as the headquarters of the Nigerian Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA). Still hooded and handcuffed the hostages are pulled out from the cars and led into a small hall. There, each of them, including the lady amongst them, is thoroughly searched and stripped naked. All their belongings are confiscated. The shackles are taken off but not the blindfold. The hostages are led down a very steep stair-case, three floors underground. Barrister Nalowa being a woman, is locked up on the ground floor. The stairs leading down to the lower levels have heavy metal doors that open up into cell-rooms.

The heavy metal doors are un-padlocked and opened. The hostages are caged in different cell-rooms. These underground cell-rooms are cold, grave-like, and divided into two sections. Barrister Eyembe Elias, Mr Tassang Wilfred, Mr Nfor Ngala Nfor, Barrister Shufai Blaise Berinyuy and Dr Cornelius Kwanga are caged in one section. Sisiku AyukTabe, Dr Fidelis Ndeh Che, Professor Augustine Awasum, Dr Ojong Okongho, Dr Kimeng Henry and Dr Egbe Ogork are caged in the other section. Each of these cell-rooms already has detainees. It later transpires that these early detainees are members of Boko Haram and the Niger Delta militia.

Neither at the time of their kidnapping in the NERA Hotel nor throughout the detention in the DIA, is a warrant of arrest presented to the hostages. No reason whatsoever is given for their abduction and detention at the DIA. They are nevertheless held incommunicado throughout the three-week duration of their detention at the DIA. They are denied access to counsel, doctor and family. They are prevented from contact and communication with each other across the sections. Each hostage is put through the third degree by plain clothes military men, some of who eventually confess they are not aware of the reason for the captivity. Some of the questions that are asked seek to elicit information about some individuals including Lucas Cho Ayaba, Ebenezer Akwanga, and a certain Nkongho Success. On January 15, the hostages caged in the section with Barrister Eyembe go on a hunger strike. The hunger strike is called off two days later when Mr Nfor Ngala Nfor collapses from exhaustion.

News of the kidnapping and detention at DIA appears to have trickled out. This prompts the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Abuja to visit the hostages on 18 January 2018 after a two-day fruitless effort to locate their whereabouts. Most of the hostages are registered refugees in Nigeria. The visit takes place in the presence of an official of the DIA and a general in the Nigerian army. During the visit, those of the hostages without refugee status inform the UNHCR that they seek asylum. They are then registered as asylum seekers. Before the meeting rises, UNHCR gives the assurance that under no circumstance would the hostages be deported to French Cameroun(Cameroun Republic) given the well-wounded fear of persecution and assassination by that country were the hostages to be taken there. UNHCR advises DIA officials to move the hostages from the extremely low-temperature cell-rooms to some other cells. Days later, they are moved without mattresses to ground-level and locked up in a cell-room.

The smuggling out

To the utter consternation of the hostages, and contrary to the assurances given by the UNHCR, on the night of 25 January 2018 the hostages are again blindfolded. Some of their personal effects are returned to them. They are led into a waiting bus. The bus drives at breakneck speed in a heavily militarised military convoy. It stops at the military section of Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport, Abuja. While there, Barrister Nalowa Bih and Dr Ojong Okongho are identified as holders of Nigerian citizenship and are taken back to DIA. The hostages are now ten.

They are made to remain seated inside the bus for an hour. The commander of the military convoy, with two assistants, walks over to two armed soldiers in black. The group has a lengthy discussion. Some voluminous documents and several black bags are produced and signed. The kidnappers happily hand the hostages over to the soldiers in black military fatigue. The soldier-driver of the bus with the hostages is ordered to move the bus to the tail of a waiting cargo aircraft at the airport. The hostages later identify the aircraft as an old, rusty, dented and faded green-coloured military cargo plane belonging to French Cameroun. It is rickety and barely airworthy.

In preparation for the transfer or, better, being ‘loaded’ into this plane, armed soldiers are made to stand in a formation of two paralleled lines from the bus to the tail of the waiting aircraft. The door of the bus is opened. The hostages are ordered out. They step out clumsily as they are still hooded and shackled. They are led through the passage way created by the parallel lines formed by the armed soldiers. When they get to the tail of the aircraft, each one is physically manhandled. Hefty men grab the collar of each person’s shirt, lift and dump him in the rusty cargo plane. Inside the plane, another group of armed soldiers concentrate on assigning each hostage to a makeshift netted-meshed seat with no seat belts or other safety device. The loading is completed. The hostages remain hooded with their hands handcuffed to the back. As soon as the tail of the cargo plane is shut, the temperature inside immediately rises! It is hot. The hostages begin to sweat. The plane taxies along the taxiway towards the run-way in preparation for take-off. Each hostage struggles to gain balance. A white pilot is in the cockpit. A colonel supervises the operation from ‘loading’ to take-off.

When the plane takes off the soldiers on board, all of them armed with automatic guns, inform the hostages that their end is at hand and that each one should say his last prayer. Two soldiers stand over each person’s head as if ready to grab him and throw out of the cargo plane. Each hostage says his last prayer in silence resigns himself to death at any moment either by bullet in the head or by simply being thrown overboard into the Atlantic Ocean to feed the fishes. After about two hours of flight time the cargo plane lands at the Nsimalen Airport, Yaoundé. The airport lights are all promptly turned off. There is a crowd of soldiers waiting.

The tail of the cargo plane is opened. The hostages, the precious cargo, are offloaded from the cargo plane. There are white buses sandwiched between military trucks wrapped in perforated military camouflages. There are also armoured cars, machine gun carriers and other military hardware. The crowd of military men at the airport is about a hundred and fifty. The hostages are hurriedly pushed at gun point into a waiting bus. They remain hooded and shackled. A long convoy of over 20 military vehicles takes off at high speed. It first stops at the Cameroun Defence Ministry. Next, it stops at the infamous Gendarmerie headquarters known in French as the ‘Secrétariat d’Etat à la Défence’ (SED). The gendarmerie is a branch of the French Cameroun military. It is generally likened to the Gestapo in Nazi Germany or Nicolae Ceausescu’s Securitate in Socialist Romania, with their torture methods. SED, now presided over by a certain infamous Col. Emile Bankoui, has therefore for decades acquired the dubious distinction of being the torture facility of the Yaoundé regime. It operates much like Auschwitz.

SED, Cameroun’s Auschwitz

At SED, the hoods and shackles are taken off. The hostages notice that they are surrounded by sinister and fierce-looking gendarmes under the authority of a certain Lt Col Serge Kaole. The gendarmes strip the hostages naked and carry out what they call ‘total body inspection’. This includes anal inspection. Thereafter, each hostage is issued a jogging outfit. This would be their daily wear and night pajamas for the next 44 days before a second one is issued. Each person is issued a small-size dirty bed sheet, a dusty and smelling mattress, and a pillow heavily stained with blood from people either beaten and wounded or dead. Each hostage is shoved into a small 2x3m² cell heavily infested with mosquitoes, cockroaches, spider web, ants, lizards, and rodents. The gendarmes make a show of attempting to control pests, rodents, and biting insects. They use rodenticides and insecticides solutions to spray the cells, often with the hostages forced to remain in the cells. On the few occasions that the hostages are herd out, the cells are sprayed and the hostages hurriedly brought back and locked up in the cells without allowing enough time for the spray to diffuse.

The hostages’ first night in SED is dreadful. But they somehow manage to sleep off for a few hours out of sheer tiredness and exhaustion from the terrifying cargo-plane flight from Abuja. Their minds seemed at peace as they ask God to take control. Early the following morning, 26th January 2018, they are given a meal of sorts. A medical team is brought into assess the state of health of each hostage. The team recommends that the hostages be provided with bottled drinking water. The director of SED and his gendarmes do everything to thwart the efforts of the medical team to attend to the hostages and to provide them the medication they each need. The SED people demonise the hostages as ‘terrorists.’ They berate the doctors saying they are too humane. They declare that government does not provide medical treatment to ‘terrorists’. Each time the hostages are given medication to treat some ailment, a certain Chi Tita and his fellow gendarmes search their cells and confiscate the medication. The gendarmes even refuse calling for emergency assistance during health crises.

For most of the time, the hostages are provided a single meal as lunch and super. On weekends, each person is provided a single meal as breakfast, lunch and dinner. The food is served on plates without any cover. The hostages have no access to a refrigerator or to a safe shelf to store away part of the food for the next meal time. After swallowing part of the food, the rest is covered with a patch of polythene material to be eaten at the next meal time. The covering is flimsy but at least it denies flies, lizards, ants, mosquitoes, and cats that often enter the cells, access to the food. The hostages are provided bottled drinking water as recommended by the visiting medical team. But this is discontinued after the first three months of incarceration at SED. The hostages are thenceforth required to drink tap water. The tap water contains metallic iron It is reddish in colour. It proves dangerous to the health of the hostages, compounding the very harsh conditions of their incarceration at SED. The hostages soon contract diseases like blurred vision, pilation, dental degeneration and cavitations, persistent rhinitis, coughing, laryngitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, dermatitis, scabies, abscession, orchitis, osteopathy, rheumatism, anaemia, malaria, gastritis, persistent myalgia, and high blood pressure. Generalised high blood becomes common among the hostages who hitherto did not suffer from that ailment. The hostages raise concerns that death might ensue should they be required to continue to drink the bad tap water. Later, glass-box water filters are provided and the hostages are then able to drink filtered water.

The hostages get some medical attention. But this is adhoc, perfunctory and strictly ambulatory. They have no access to hospital treatment. Whenever one of the hostages falls ill, the gendarmes refuse to call for a doctor or to send him to the hospital for diagnosis and treatment. For instance, there is this occasion when Mr Nfor Ngala Nfor suffers a diabetic crisis. It is only with the greatest reluctance that the detaining authority at SED accepts, after many hours; to convey him to a local infirmary. The delay could have cost his life. The gendarmes at SED verbally abuse the hostages ever so often. They call them all kinds of hate names, saying they are “worse than slaves” and deserve no mercy.

Most of the gendarmes at SED are extremely wicked and callous as if drained of anything human in them. The hate speech they use includes calling the hostages: ‘terrorists’, ‘worst then slaves’, ‘beasts’, ‘savages’, ‘Anglofools’, ‘Nigerians’, ‘Biafrans’, ‘people abandoned by the English’, ‘pest’, ‘rats’, ‘dogs’ etc. The gendarmes even prevent the hostages from praying be it individually. They train their guns on each hostage whenever he tries to pray. Searches are conducted at least twice a week. Each hostage is stripped naked on every search occasion. During a search, the hostages are abused, humiliated, insulted, and treated contemptibly and with indignity. The gendarmes walk into the cells with muddy feet, overturn the mattresses, and pull off the smelly bed sheet. Every night they play martial music. They mask themselves, bear heavy automatic weapons, and keep guard at the cell doors like ghosts. They refuse to provide the hostages with bathing soap and detergent for washing the jogging outfit and the smelly blood-stained sheets which are then ‘washed’ without soap. The hostages are constrained to sleep in the wet jogging outfit and on the wet sheet. They sleep on broken, pricking metal-spring mattresses with thick caked blood stains all over.

For the first six months, the hostages’ are caged in cells all day long, every week and every month. The cell doors are opened sparingly. The only ventilation into the cells is apertures at the large heavy metallic doors. These doors initially had fenestrated airspace of 60cm by 60cm but are now reduced to 60 cm by 30cmusing welded and painted machine-trimmed metallic sheets. This mischievous piece of work is carried while the hostages are compelled to remain in the cells. The pneumonic disturbances and the inhalation of toxic smelly paints mean nothing to the gendarmes. The outer walls of the cells are reconstructed by doubling from bottom to top with concrete 30cm thick in width. The design and purpose appear to be to induce a coffin-like or a buried-alive phobia, a satanic form of torture. Throughout the duration of that piece of work, the hostages are daily subjected to severe pneumonic disturbances from 7 a.m. till 6 p.m.

At SED, each hostage is taken out in turn for prolonged interrogation. The interrogation is always at midnight. Each person is blindfolded and dragged for over fifteen minutes through narrow, muddy and bushy paths that lead to a dirty storage facility for old military odds and ends. In the process of being dragged on the ground, the supplied jogging outfit becomes dirtier and filthier. The dilapidated storage place is fitted with very bright floodlights, overhead studio cameras, and old dusty desktop computers. There are also smelling boots and torn clothing lying about. The hostage is ordered to sit on a broken wooden chair placed facing the floodlights and cameras. Two plain-clothes gendarmes conduct the interrogation in the presence of heavily armed, hooded gendarmes. The interrogation session usually takes two to three hours. Each hostage is subjected to at least four nocturnal interrogations per week. During the first six months the hostages are caged in their cells and denied even access to sunlight. On the very rare occasions when access to sunlight was allowed, each exposure to sunlight lasts no more than15 minutes. On each of those occasions, the hostages are accompanied by over 15 heavily armed gendarmes, each with a hood over his head and hands in black gloves.

Daily flagellation of the Taraba 37 and the Calabar 11

The gendarmes at SED are gloomy and pitiful specialists in physical, mental, and psychological torture. The director of SED oversees the torture sessions. At SED there are also other shackled hostages, citizens of the Southern Cameroons (Ambazonia). These compatriots are known as the Taraba37 and the Calabar11, making 48 in number. They were kidnapped in Taraba and Calabar in Nigeria, hence the name Taraba 37 and Calabar 11. Day in day out the 48 suffer merciless flagellation at the hands of the SED gendarmes who clearly derive sadistic pleasure and satisfaction in inflicting pain, cruelty and suffering on others. The gendarmes get in the air-tight cells of the 48, flagellate them and then pour sewage water on them. Every day the 48 are taken out for torture, cruel and inhuman and degrading treatment. They are chained, blindfolded, and further restrained using slave-type shackles. They are then led to a place the gendarmes at SED gruesomely name with satanic relish as the ‘slaughter house’ or the ‘point of no return’. They are dragged through the narrow corridors, their heads bumping against the walls.

In the ‘slaughter house’, the 48areflagellated from 9 p.m. to about 4 or 5a.m. while still shackled and blindfolded. The flagellation objects include clubs, high-tension electricity cables, and metal pipes. When each victim succumbs to these beastly beatings, he is hung on ropes fastened to their arms, waists and ankles. A 50kg cement bag or a pile of bricks is then placed on his back. The gendarmes keep him in that position until he becomes completely dehydrated. The gendarmes on the next shift of duty at SED signal their arrival by sadistically flagellating the 48 for an hour, from 5 a.m. to 6 a.m. and are then taken back to their cells, bleeding profusely. During these cruel torture sessions, they cry out continuously until they lose their voices and pass out. The SED gendarmes torture their victims in this manner for over 5 continuous months. The torture is also meant to inflict collective pain by association and to cause psychological trauma and depression in all the Southern Cameroons hostages.

15 months’ old baby detained in SED

A particularly barbarous case of torture is that of 15 months’ old baby Moses Ndokia (real name withheld). He is always restless due to the conditions at SED. He is ever hungry because he is ill-fed. He continually cries for food. This baby was abducted in Calabar together with his mother and father. He is in SED since March 2018. This is particularly traumatizing. For over four months Baby Moses is subjected to humiliating and inhuman treatment. Mercifully, mother and child (but not the father) are subsequently released when news filters out that a 15 months’ old baby is being detained and tortured at SED.

Family visits after six months of incommunicado detention

The Nera 10 hostages are held incommunicado at DIA, Abuja, Nigeria, for three weeks, from January 5th to January 25th. At SED, Yaoundé, they are also held incommunicado, this time for six months, from the 25th January 2018 to the end of June 2018. Only after this period are family visits allowed. Visiting time practically lasts only 15 minutes. Only one visitor per visiting period is permitted. Most times the gendarmes refuse to unlock the doors of the cells for hostages to meet their visitors. On several occasions family members who have travelled long distances to visit get to SED only to be turned back saying all visits are cancelled. Each visitor is required to speak only to the family member he has come to visit, to the hearing of the gendarme on duty and in no local language. Physical contact with visitors is not allowed. Often the hostages are forced to speak to their visitors behind transparent glass screens. Protest against this treatment is given short shrift.

The belongings of the hostages – cloths, belts, shoes, caps, hats, inner wears, gold necklaces, bracelets, watches, pens, purses with moneys, documents, and house keys – confiscated upon arrival in Yaoundé have until date not been returned to them. Similarly, other personal effects such briefcases, bags of shoes, laptop bags, laptops, external hard drives and other computer accessories, money, documents, students’ theses/dissertations, bank cards, telephones, and so on are still in the keeping of SED.

Kondengui, Cameroun’s Bastille

On the 22nd of November, 2018 the Nera 10 hostages are moved to the equally notorious Kondengui incarceration facility. This is a maximum security ‘prison’ located some ten km at the other side of Yaoundé. Here too, conditions are no better. They are generally horrible. The living space is a small 12 m² accommodating a minimum of 12 inmates. The rooms are poorly ventilated. The smell from the toilets is appalling, especially when there is no water which happens every week. The sleeping spaces are infested with vermin: rats, cockroaches, mosquitoes, lice, bedbugs and other noxious biting insects, most of which suck blood and leave behind deep wounds and scars. The environment itself is a playground for rodents and roaches. Nearby smelling heaps of rubbish take days to clear! The daily stench from there is horrible.

The ‘food’ is not fit for human consumption and is provided only once a day. Medical care is practically non-existent. In May 2020, there was an outbreak of Covid-19 in the prison. Over 60% of the inmates’ fall ill at the same time. There is a brief riot that compels the administration to put everyone on Covid-19 ‘treatment’ plan for 7 days. With the assistance of family, friends and others, sanitation, health and feeding situation has improved.

The hostages arrive Kondegui prison on the 22ndNovember 2018 at about 6 pm after having been taken to an official said to be the presiding officer of the tribunal militaire, Yaoundé. He records the names of each hostage and such other particulars as he is minded to request. Beddings and medication belonging to the hostages are in polythene bags. These are ordered to be handed over to the prison warders at the warder post for security screening. The warders also do a body search on the hostages. The prison discipline officer then takes them into his office for briefing on prison rules and regulations and payment of what he calls ‘new man tax’ (a ‘tax’ payable by a new inmate). From there each hostage is allocated a cell-room in which there were already other prisoners and detainees. There, the chief of the cell-room briefs the newcomers and demands payment of ‘new man tax’. Then beds are allocated. The minimum number of inmates per cell-room is 13 persons cramped into these small-size rooms of about 4 m x 7 m x 9. The bunk beds are 3 or 4 bed levels high and usually with someone lying directly on the floor. The toilet space is 2 m x 2 m for a shallow pit toilet and an overhead shower in the same place. The inmates in the cell rooms are forced to smell and inhale the odour from the toilet 24/7.The prison has a court yard where inmates interact with each from 7.30 am to 6.30 pm daily. It is there also that inmates have morning devotion, eat at meal times, and manage to play some games of sort and perform other exercises. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, that is also where visitors were received.

The story of the armed kidnapping of the Nera 10 in Abuja and armed smuggling to Yaoundé under cover of darkness; the story of their incommunicado detention at DIA and later at SED; and the story of their nocturnal ‘trial’,‘ conviction’ and ‘sentence’ to life by French Cameroun’s Tribunal Militaire – all this is shrouded in complete mystery and illegality. It is now known that the Nera 10 were kidnapped by plain clothes Nigerian military in a joint operation with members of French Cameroun’s military. It is now known that they were smuggled out to Yaoundé by members of the armed forces of French Cameroun with the complicity of Nigeria’s military. The illegality of their seizure has further compounded the illegal refoulement of all ten of them, refugees and certified asylees, back to French Cameroun, back to the regime and country from which they are escaping persecution and possible death. Upon arrival in Yaoundé and after about a year of detention at SED under atrocious conditions the Nera 10 are moved to the cramped and insalubrious life-threatening Kondengui prison, and then arraigned before the Tribunal Militaire, Yaoundé- a terror agency of the Yaoundé regime. After more than a year and a half of detention, the Nera 10 are hurriedly brought before that tribunal on a certain night and put through the motion of a ‘trial’ under cover of darkness. They are denied access to counsel. They are not given the opportunity to be heard. They are ‘convicted’, and ‘sentenced’ to life imprisonment and a fine of more than US$525 million each.

By Professor Carlson Anyangwe

[NB. This poignant narrative has been put in the historic present tense. This style puts the reader inside the situation being described and gives him the feel of being right there. It enhances the sad drama and its readability.]