Southern Cameroons Crisis: Will schools ever start in rural Southern Cameroons?

It is over five years since schools in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions were shut down because of a dispute between the country’s English-speaking minority and the Yaounde government over key issues the government was reluctant to address.

English-speaking Cameroonians had complained of marginalization in 2016, and many held that the quality of education in the two English-speaking regions was deliberately being watered down as the government posted French-speaking Cameroonians to teach English-speaking Cameroonians in French even when the students could not understand French.

Lawyers, who were also at the forefront of things, also complained about deliberate attempts by the government to erase the common law system from Cameroon. All peaceful attempts where completely ignored by the Yaounde government which has always held that only brutality and military violence could address any socio-political difference in the country.

As the government sought to change things by force, matters only got worse, as schools and universities were shut down and ever since, many rural schools are still closed, with armed separatists enforcing a shut-down which has been condemned all over the world.

In certain cases, separatist forces which are not controlled by any real chain of command, even undressed students who wanted to go to school. They have been accused of burning schools, intimidating students, and killing teachers in rural parts of the English-speaking parts of Cameroon.

There are thousands of children who have been robbed of a bright future due to a conflict they know nothing about. Those who call the shots among the separatists are incapable of calling off the school boycott as some rogue elements have transformed the school boycott into their stock-in-trade.

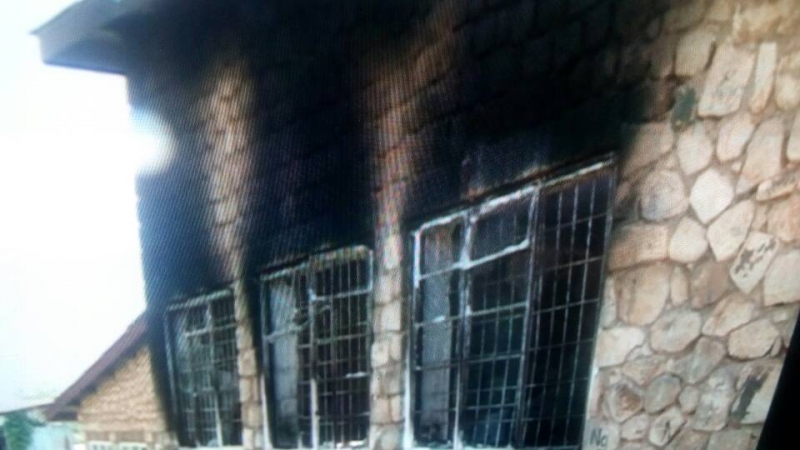

Some people or groups of people are permanently ensuring that schools in the two English-speaking regions of the country do not resume. Each year, when its is time for the resumption of the school year, a school is burnt down as a strategy to sow fear in the minds of many parents who may want to send their children to school.

Last week, a dormitory in the Presbyterian Secondary School in Mankon in the Northwest region was burned down by some armed men who sent out the students from the dormitory before setting the structure ablaze.

The incident bore the hallmarks of the separatists who, for five years, have insisted that children should be kept at home, a strategy which has not given the revolution a good name.

The government, for its part, has not changed its strategy. Despite calls from people around the world for a negotiated settlement, the Yaounde government has continued to operate as if the education of those children is not important.

From every indication, schools in rural parts of the two English-speaking regions of the country will remain closed as separatists marauding the streets of small towns and villages are spreading word that parents should keep their children at home again this year, making it six straight years that these children have not been to school.

If things must change in this regard, the government must make some painful decisions and one of such decisions will be bringing the separatists to the negotiating table so that children who never bargained for what is happening to go back to school as a means of guaranteeing them a better life in the future.

By Dylan Tambe Ashu