Southern Cameroons Crisis Is Now a Full-Blown Civil War

Since 2017, Cameroon has been engulfed in a bloody civil war that has claimed more than 6,000 lives, forced more than 1 million people to flee their homes and left nearly 4 million people dependent on humanitarian assistance. Diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict have repeatedly failed, most recently in January, when a Canada-backed initiative was aborted before it even got off the ground. Now divisions among the armed separatist movement fighting the government risk escalating the conflict, raising further obstacles to reaching peace.

The conflict has its origins in protests that began in 2016 over language-based grievances in the Anglophone North-West and South-West regions of the majority-Francophone country. Led by lawyers, students and teachers, the demonstrations sought to block a new measure that imposed French-speaking teachers and judges in Anglophone schools and courts, while also calling attention to the broader marginalization of Cameroon’s Anglophone population, which constitutes roughly 17 percent of the country’s inhabitants.

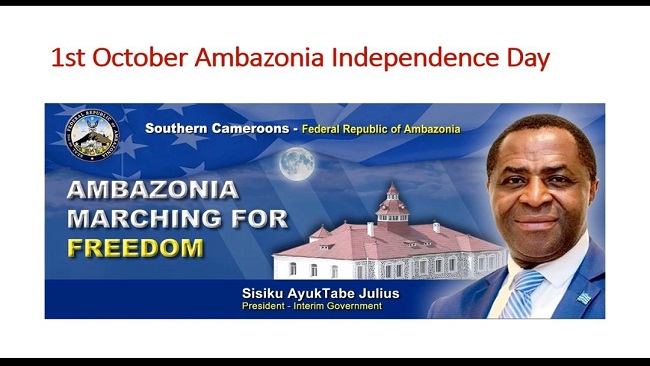

After authorities brutally repressed the peaceful protests, a previously existing separatist movement radicalized and began to launch attacks against government forces the following year. In October 2017, Anglophone secessionist groups declared the creation of an independent Federal Republic of Ambazonia, with the Ambazonia Governing Council at its head. The following month, the Cameroonian government declared war on the secessionists and deployed soldiers to the Anglophone regions to crush them.

Since then, the violence has escalated into a full-blown civil war that has raged on despite domestic and international efforts to broker peace. In 2019, peace talks mediated by Switzerland followed by a week-long national dialogue initiated by the government failed to halt the fighting, partly due to infighting among the separatists. The following year, another dialogue involving several jailed members of the separatist movement’s leadership collapsed, this time due to divisions in the Cameroonian government as well as among the separatists.

The Canada-facilitated dialogue between the Cameroonian government and Anglophone separatists announced by Canadian Foreign Minister Melanie Joly in January was the latest high-profile attempt to “reach a comprehensive, peaceful and political resolution of the conflict.” But three days after Joly’s announcement, a Cameroonian government spokesperson shot down the proposal, saying that Yaounde did not entrust any country with the role of mediating the crisis.

But while Yaounde took the blame for scuttling the most recent initiative, some observers chalked up the abortive dialogue to internal disagreements among the Anglophone leaders. In an exclusive interview with World Politics Review, Capo Daniel, the former spokesperson of the Ambazonia Governing Council, which represented the separatists in preliminary discussions, said that “internal politics” within the organization’s hierarchy is as much to blame as Yaounde’s intransigence for the failure of the Canada-initiated peace talks.

The Hong Kong-based separatist leader was part of the Anglophone negotiating team at “pre-talks” between the Cameroonian government and the Anglophone separatists. But he resigned from his position as spokesman for the council and its military wing last month, citing fundamental disagreements with the movement’s leaders. “We had strong divergent views in the leadership, both about the commitment we secured from the state of Cameroon and the Canadians that facilitated the process,” he told WPR. “The commitment was for a negotiated settlement, but we failed due to the internal politics and the divided nature of our camps.”

The historical origins of the Anglophone crisis date back to the end of World War I, when German Kamerun—as the colonial territory was then known—was divided into two League of Nations mandates. Britain took over roughly one-fifth of the territory along the borders of neighboring Nigeria, while France assumed control of the remainder. When French Cameroon won its independence in 1960, the U.N. organized a plebiscite the following year to determine the fate of the British Cameroons. But that referendum offered voters only two options: to merge with either Nigeria or Cameroon. Northern Cameroon voted for union with Nigeria, where its former territory now makes up parts of Adamawa, Taraba and Borno states. Southern Cameroon opted for union with Cameroon.

To this day, many Anglophone Cameroonians consider the 1961 plebiscite to be an injustice. According to Samuel Ikome Sako, the president of the unrecognized Federal Republic of Ambazonia, that referendum presented Southern Cameroon with “two bad options,” instead of the self-government that many desired.

In the years after unification with Cameroon, a federal system was established to administer the country and preserve a sense of autonomy in the Anglophone regions. In that system, both English and French were established as the country’s official languages. But beginning in 1972, then-President Ahmadou Ahidjo introduced a process to centralize authority, which ultimately abolished Cameroon’s federal system, further concentrated powers in the hands of the president and effectively imposed a Francophone character on the Cameroonian state.

Cameroon’s civil war has now metastasized, turning most parts of the Anglophone regions into a battlefield between separatist militias and government forces.

It was against this backdrop of distrust and disillusionment that the 2016 demonstrations and civil disobedience erupted, triggered by policies that were seen as attempts to further erode the Anglophone regions’ language status and exacerbated by Yaounde’s brutal response to the peaceful protests. Ever since then, the conflict has metastasized, turning most parts of the North-West and South-West regions into a battlefield between separatist militias and government forces. There have been 30 attacks by separatist militias and Cameroonian security forces since January, with the violence taking place in rural communities like Bali, Bache, Bambui, Oku, Kumbo and Jakiri near the Nigerian border, but also in cities like Bamenda and Buea, where one person died in a separatist attack on April 10.

In addition, more than 700,000 children have had their education disrupted due to regular attacks by armed groups trying to impose school boycotts. The United Nations estimates that two out of every three schools in the Anglophone regions have closed indefinitely. This is aside from grave human rights abuses—including mass killings, rape, torture, assault and kidnappings of civilians—committed by both sides, according to Human Rights Watch.

The breakdown of the Canada-backed peace initiative now risks escalating the conflict indefinitely. As a result of the collapsed talks, violence spiked across the two Anglophone regions in February and March. This included the killings of unarmed civilians in Muea by Cameroonian troops and the brutal assassination of Chiabi Emmanuel—a prominent academic—by a nonstate armed group in Bamenda, the capital of the North-West region. On March 15, two students at the University of Buea were arrested by Cameroonian security forces, accused of links to separatist fighters. Hours after their arrest, one of the students, Ngule Linus, died in custody, prompting calls for an investigation.

Daniel, the former spokesperson for the Ambazonia Governing Council, has since launched a new movement called the Ambazonia Peoples Rights Advocacy Platform, with the goal of renewing efforts to resolve the conflict. He is looking to use a constitutional clause called “Special Status” that enables the central government to “take into consideration the specificities of certain Regions with regard to their organisation and functioning,” in order to enhance the Anglophone regions’ powers of self-governance.

President Paul Biya already used the clause in 2019 to institute measures that transformed the Anglophone regional councils into more powerful regional assemblies, with authority over the local education system, regional development institutions and relations with traditional chiefs—all powers that the Francophone councils do not have. But a report by the International Crisis Group argued that Yaounde “undercut the impact and legitimacy of the 2019 measures by filling the assemblies with government proxies and giving veto power over their decisions to the centrally appointed governors.”

Daniel’s goal is to see whether more concessions can be won beyond the limited autonomy granted by Biya four years ago. But many critics, including among the separatists, argue that this approach would not go far enough in granting autonomy to the Anglophone regions, where popular opinion since 2017 has oscillated between federalism and secession. Given the absence of opinion polls, it is difficult to gauge the extent of public support for secession. But it is clear that many English-speaking Cameroonians do not trust that their rights will ever be fully guaranteed if they remain in the union.

But in addition to the flaws in the Special Status approach, it is not clear how many within the separatist camp will accept Daniel’s leadership. Tse Anye Kevin, one of the organizers of the 2016 protests, dismissed Daniel’s credibility, blaming him and other separatist leaders in the diaspora for “creating chaos on the ground.” Kevin was the deputy president of the Confederation of Cameroon Trade Unions in 2016, but in the wake of the brutal repression that followed the protests he fled to Nigeria, where he remains. While still active in efforts to attract international attention to the Anglophone crisis, Kevin is critical of the factional struggles among Ambazonian leaders, which he considers to be the major obstacle to achieving freedom for Cameroon’s Anglophone communities.

He nonetheless believes that, despite the disunity abroad, the disparate groups that make up the liberation movement on the ground in the Anglophone regions—including their armed factions—are willing to work together. But that might be too optimistic. Following his resignation from the Ambazonia Governing Council, Daniel promptly assembled fighting units loyal to him under a new group called the Ambazonia Dark Forces, with the intention of launching a campaign of economic sabotage targeting the Biya regime’s investments in the Anglophone regions.

The aim, according to Daniel, is “to cripple the Biya regime and force it to agree to a cease-fire by denying it economic revenues.” But that will mean further escalation of the conflict, both with the government and potentially among the separatists, with all the implications that holds for the residents of the region.

Culled from World Politics Review