President Trump wish to buy Greenland exposes US imperialism

From his love of tariffs to his racial view of the world, Donald Trump is the nineteenth-century president America never had. Yesterday, the Wall Street Journal offered another piece of evidence suggesting that the 45th president is a man out of time: the president, it turns out, has frequently mused aloud about buying Greenland from Denmark. (Greenland, although largely self-governing, is alongside Denmark and the Faroe Islands, one of the three constituent countries of the Kingdom of Denmark.)

Like Trump’s racism and trade policies, there’s a precedent for American officials trying to buy territory. Most Americans know, vaguely, that the United States acquired much of its territory by buying it. Some acquisitions, like the Louisiana Purchase, are well enough known to be the subject of TV ads. Others are more obscure, like when Secretary of War Jefferson Davis and other Southerners pressed for the purchase of enough of northern Mexico to support the construction of a Southern transcontinental railway.

In fact, buying Greenland has been tried seriously twice. But the changes in international relations since then make it a far worse idea than it was at the time.

The first time came during the administration of President Andrew Johnson. William Seward, a Lincoln holdover, used Johnson’s distraction over Reconstruction to pursue his longstanding goals of territorial expansion.

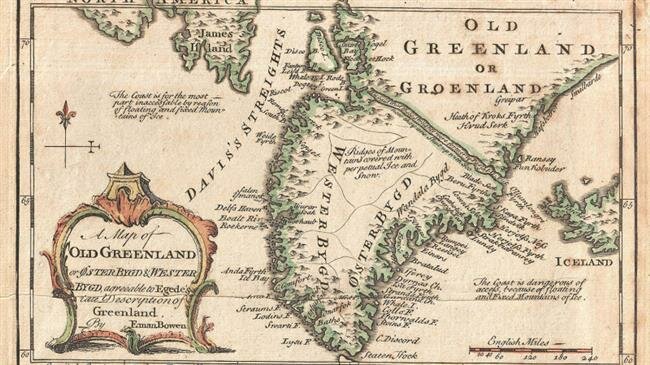

Seward made bids of varying intensity to wrest Canada from the British Empire and to buy or lease a naval base in the Caribbean. His buccaneering policy finally paid off with the Alaska Purchase, when the Russian Empire, seeking to divest itself of some under-performing assets, finally succeeded in persuading Seward to buy Russian North America. But it also included an attempt to buy Greenland and Iceland from Denmark, which then owned both.

Robert J. Walker, a former treasury secretary and influence-peddler in the mid-nineteenth century, learned that Denmark might be induced to sell the islands in 1867 as he negotiated the purchase of Denmark’s Caribbean colonies in the West Indies. Seward leapt at the chance and commissioned Walker to produce a gushing report on the resources of Greenland and Iceland.

Walker’s covering note to the report marveled at how buying the two islands could lead the United States to greatness. Although he admitted that basically nothing of Greenland’s north or interior was known, it nevertheless pounded what facts it could master, such as that Greenland was “the largest island in the world” and that it possessed “whale fisheries…of the value of $400,000.”

Seward’s hopes that the United States could make a bid for the islands came to naught when his deal to buy the Danish West Indies failed in the Senate, even though the treaty for purchasing them had been ratified by both the Danish parliament and a plebiscite in the islands. (They would be purchased fifty years later and became the US Virgin Islands.)

The second attempt came in the aftermath of the Second World War. Denmark, which still administered Greenland as a colony, was conquered in a six-hour operation in March 1940. A year later, the Danish ambassador, who retained his credentials even though he refused to take orders from the occupied government in Copenhagen, signed an agreement with the US government allowing it to occupy and fortify the island to prevent Germany from using it as a base against the US and Canada.

The wartime occupation of Greenland let the United States develop several military installations there, including an airbase.

The Trump administration’s obsession with trade threats, tariffs, and bullying both allies and rivals into submission was based on an ambitious theory. It turned out to be a fallacy.

The possibility of buying Greenland was floated seriously enough that in February 1946 Gallup polled Americans whether they should pay one billion dollars to buy Greenland from Denmark. Thirty-three percent of Americans said yes, while 38 percent said “no”. Twenty-eight percent had no opinion, which seems fitting given that only 45 percent of respondents correctly identified where it was and only 10 percent knew how many people lived there.

Americans did, however, have a good understanding of what Greenland’s potential value, with a majority naming military uses for the island as its chief value. In that, they followed the trend in Washington, where senior policymakers and military officers viewed the control of Greenland as “indispensable to the safety of the United States”. In the end, the Danes turned down the bid, and offered Greenland greater status as a full part of the Kingdom of Denmark instead of a colony.

Yet Cold War tensions meant that the United States got what it wanted anyway: a series of military installations throughout the island. These air bases and other facilities played an integral role in US nuclear strategy, as the Danish political scientist Nikolaj Petersen has written. For the first part of the Cold War, US nuclear deterrence of the USSR rested not on intercontinental missiles but on bombers with comparatively limited range. Greenland offered a way to make a route to targets in the Soviet Union flying over the polar regions reliable and effective. And when the United States demanded additional bases, Denmark acquiesced.

Trump’s musings probably won’t amount to a third serious bid. It’s worth noting that, so far, nothing has come of the idea beyond a few reported musings at dinner. On the other hand: this is Donald Trump, so this trial balloon might take flight at any time–and that means it’s worth exploring why this would be a terrible idea.

For his part, Trump seems less than well briefed about the island and motivated more by ego than strategy. The Journal’s source believes that Trump wants to complete a deal both because of its natural resources and because it might leave him a legacy “akin to President Dwight Eisenhower’s admission of Alaska into the U.S. as a state.” (Hawaii doesn’t count, perhaps because Obama was born there.)

Admittedly, Greenland probably has substantial oil reserves – and a certain strategic importance. Secretary of Defense James Mattis pressured the Danish government last year to put on ice an attempt by Greenland’s prime minister to have China finance three airports on the island, while global warming – that well-known Chinese hoax – might create new shipping lanes right by it.

But there’s more than a few obstacles. First, even though governments (or government-backed companies) can buy land in other countries, it’s not clear that countries in general can buy or sell sovereignty over their territories anymore. Even by the early twentieth century, this was becoming an oddity–and the practice of swapping territories as part of power politics or for fiscal reasons became all but discredited by the middle of the twentieth century, in line with the development of norms discrediting imperialism and treating countries as the property of the sovereign. That goes double for places with large indigenous populations, like Greenland, where 88 percent of the residents are Inuit.

Greenland is no longer a colony to be disposed of as the government in Copenhagen wishes

Greenland is no longer a disposable colony: Denmark

Today the Danish doctrine of the “Unity of the Realm” holds that Greenland forms an integral part of the three-country Kingdom of Denmark. To put it bluntly, selling off Greenland would be as unthinkable as the US selling off Hawaii or Delaware.

Even if country-selling were legal generally or specifically, the United States shouldn’t be in the business of engaging in the trade – however much Washington has treated Greenland as a colony in the past.. When in 1968 a US Air Force B-52 crashed in Greenland, after all, the people who were exposed to the chance of a nuclear disaster had never been given a chance to agree to becoming a US base, and the toxic remnants of US nuclear presence still haunt the island.

As a democratic country, the United States bears a special responsibility to refuse to perpetuate territorial practices. Yes, the island has only 57,000 people–about the size of Terre Haute, Indiana–but they form a distinct political community and already enjoy self rule in everything but defense and foreign affairs. Right now, there’s reason to think that Greenland may well be on a path to full independence, not simply switching one protectorate for another.

Could the United States offer Greenland’s people a better deal? Probably not. The Trump administration’s neglect of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands after Hurricane Maria forms only the most recent in a long chronicle of US mistreatment of its colonies. The US still holds more than four million people as colonial subjects in islands from Guam to the Northern Marianas – and they get a worse deal than mainland Americans on every score. And who would trade the Danish healthcare system for the American one anyway?

Unless the island were to become a state, Greenland’s fate would likely be more like those other insular possessions. And if Greenland did become a state, it would not only make the Senate even more mal apportioned than it already is but it would be a slap in the face to the US territories and the disenfranchised residents of the District of Columbia.

And all of this, of course, doesn’t consider what would happen if, by some unlikely set of events, such a deal were concluded. Just imagine a world of great-power competition in which Russia, India, and China engaged in a new, suddenly-legitimate scramble for colonies.

The notion of buying Greenland, then, isn’t a silly idea, no matter how lightly the president may have proposed it. It’s a dangerous and a telling one that suggests that the president’s impulse to treat everything as a real estate deal means that he’s constantly tempted to bring back some of the worst habits of international relations.

(Source: Foreign Policy)