Pathways to Peace in Cameroon: Ten Critical Observations for the International Community

In October 2022, Cameroon marked a poignant anniversary: six years of an avoidable crisis that escalated to civil war, one which has killed thousands and displaced or severely impacted millions. I wrote an early overview of the crisis for CGAI in September 2018, at which point I had no idea the war would get worse and still be raging four years later. Yet, in the litany of armed conflicts afflicting the world today, Cameroon still barely rates a mention. President Paul Biya’s government has worked hard to play down what evolved into a civil war by early 2018 while it plays up cosmetic attempts to address longstanding political grievances that led to this crisis. That diplomatic effort continued September 26 when Foreign Minister Lejeune Mbella took to the podium at the United Nations General Assembly. He emphasized implementing outcomes from the Major National Dialogue (October 2019), including belated decentralization efforts and special status for two anglophone regions, expanding a premature and chaotic disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) initiative and seeking reconstruction funds from international donors. However, the war is not over. The suffering continues and there is no political or peace process underway to address grievances that go far beyond 2016 to 1961.

In September 2022, the Cameroon government ungraciously terminated a struggling, often disparaged, Swiss-facilitated mediation process launched in 2019. The government never seriously engaged and even those opposition stakeholder groups involved were never convinced of its authenticity. Instead, it has become clear that the government is doubling down on its hammer-and-lies strategy: keep up the military pressure even if that means more civilians killed or displaced, discredit the “separatists and terrorists” at every opportunity within an opaque information environment and try to convince the international community that cosmetic political fixes have real substance. This is a strategy for regime maintenance alongside continued violence, misery and long-term instability in the region, not a pathway to either victory or peace.

Despite six years of escalating conflict, finding a viable pathway to peace in Cameroon might be easier than ending Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, stopping violence across the Sahel or eastern Congo or reversing the Taliban’s predictable impoverishment of Afghanistan. Anyone – and it will take mostly brave Cameroonians with the help of outsiders who can mobilize international pressure – willing to take on this task needs to understand the complex lay of the land in 2022 after six years of evolving conflict dynamics. As the United States (in August) and even Canada (in the near future) launch new foreign policy strategies for Africa, Cameroon offers a painful but typical case study of the close connection between bad governance, civil war and international apathy. After a brief overview of the anglophone crisis, I present 10 critical observations designed to alert external stakeholders to contemporary realities and dynamics that, if ignored, limit the possibilities for achieving either peace or justice.

Understanding the Anglophone Crisis

The trigger to the current anglophone crisis – a useful shorthand that some stakeholders legitimately reject for making the conflict sound like it is just about language – occurred in October-November 2016. English-speaking lawyers, teachers and students peacefully protested the appointment of French-speaking judges, teachers and administrators in the two English-majority regions of the country, as well as the lack of translation of key laws and regulations into English. Cameroon is roughly the reverse of Canada, with approximately 70-75 per cent who use French as their common language compared to 25-30 per cent who use English or a Pidgin form (of course, many Cameroonians speak both French and English/Pidgin). The French-English divide is rooted in a colonial past that saw the British Southern Cameroons “achieve independence by joining” ex-French Cameroun in 1961 through a problematic, and some argue incomplete, UN process. The French-English divide glosses over a tremendous diversity of ethnic groups, languages, dialects, traditional authority structures and religious practices, but it remains politically and economically salient in the 21st century. Common-law lawyers worried about judges trained only in civil law and teachers watching non-English-speaking teachers appointed in English-language schools took to the streets and went on strike but were beaten, humiliated and arrested by mainly French-speaking security forces. Some remained in prison for weeks or months.

October-November 2016 exemplified for many that those longstanding grievances about the English-speaking minority’s political and economic exclusion – and the country’s failed attempt to either democratize or decentralize since promised political reforms in the 1990s – would never be solved without concerted action. The ballot box had long been forsaken as a route to political change. Despite a fast-growing population, the number of those actually voting has declined for every election since 2011. Lack of political avenues led to various civil society groups mobilizing both within and outside the country, including some who eventually took up the banner of outright independence as the only permanent solution. While the independence (or “restoration”) option is not new in Southern Cameroonian political discourse, it gained currency in direct reaction to the violence and intimidation brought to bear by government security forces during 2016-2017 as they attempted to suppress civil society groups agitating for real change.

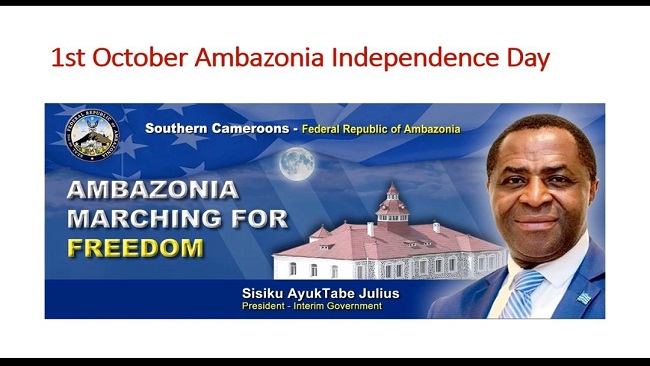

After mass demonstrations began on September 22, 2017 across the two anglophone regions, suggesting broad support for independence or at least significant political reforms, security forces responded with deadly force, including shooting peaceful protesters from helicopters. On October 1, 2017, one leading group declared independence for Ambazonia, following the borders of the old British Southern Cameroons trusteeship. The first small attacks on security forces followed in November 2017. Subsequently, state radio reported that Biya “declared war on these terrorists who seek secession.” A group of 10 distinguished Southern Cameroonian independence leaders, most of whom were in senior positions at Nigerian universities, including President Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe, were arrested in Abuja, Nigeria in January 2018, extradited to Cameroon, imprisoned and eventually tried and convicted under an anti-terrorism law designed to target Boko Haram militants.

In February 2018, the government set up a new regional military command at Bamenda and began to expand military and police facilities near the airport. Thus, from late 2017 through 2021, the low-level insurgency evolved into a civil war, with thousands of combatants and civilians killed, hundreds of villages and public buildings razed, millions of civilians displaced either temporarily or permanently and thousands more kidnapped for ransom or bribes. Where once local Ambazonian defence militias were armed only with homemade shotguns (Dane guns) and heavily outgunned by security forces, by 2019-2021 they were mostly equipped with captured assault rifles and machine guns. They regularly employed IEDs against military convoys, occasionally used small drones and RPGs and periodically carried out raids beyond the borders of the anglophone southwest (SW) and northwest (NW) regions against military and police outposts.

The Cameroon government, suffering an economic crisis of its own making during the latter half of the 2010s, still preferred to use scarce financial resources to expand military recruitment and import additional weapons, armoured vehicles and helicopters. It then announced a DDR program in late 2018 to try to convince the outside world that the war was effectively over before it began. Ongoing international loans from the International Monetary Fund, China and from European commercial banks (for soccer stadiums) directly or indirectly enabled the government to finance its military solution to a fundamentally political problem. The Swiss-led peace process, funded in part by Canada and others, ramped up in 2019 but unfortunately only added to the division and mistrust among anglophone groups as it failed to deliver any meaningful process to engage a recalcitrant regime. Its demise opens the door for others to develop new pathways to peace.

Ripe for Resolution?

Thus, after six years, the anglophone crisis should be ripe for resolution. People on the ground are tired of war, of interrupted schooling for their children, of constant economic stresses, of incessant harassment by soldiers and police who seem more like occupation forces and by certain “Amba boys” who act as bandits rather than freedom fighters. Some security personnel suffer low morale and others try to avoid postings in the anglophone regions altogether. Anglophone groups in the diaspora are constantly at odds, with various leaders claiming others are “black legs” (traitors), while those doing the actual fighting often complain they haven’t received promised financial contributions from overseas supporters. The Cameroon government and many of its state-owned enterprises are verging on debt distress that higher oil and natural gas prices cannot fix. And in Yaoundé, political factions are preparing for the day when Biya, in power since 1982 and now 89 years old and rarely seen in public, can no longer rule.

Ultimately, this crisis will not be settled by force of arms, even as the security forces claim tactical victories when they eliminate some of the Ambazonian generals and field marshals who lead small units. Those small units are sometimes closely or loosely affiliated under banners such as the Ambazonia Defence Forces and Ambazonia Restoration Forces. After six years of acute crisis, but decades of marginalization and autocracy, there is still enough anger and momentum for Ambazonian armed groups to persist and often grow despite setbacks. Social media on October 1, 2022 displayed multiple independence celebrations across the NW and SW regions, including parades by well-armed and well-trained Ambazonian units. The appeal of independence is much broader today than six years ago precisely given the government’s ham-fisted approach to the crisis. Although the “road to Buea” (a euphemism for independence, as Buea was the capital of British Southern Cameroons until 1961) is still pitched by some Ambazonian leaders as a more straightforward process than domestic, African Union and global politics will allow, a series of non-scientific surveys have shown a growing preference for, or at least resignation to, the idea that outright independence is the last, best solution to the crisis.

Where once the idea of a properly resurrected federalism offered many anglophones (and francophones) hope for a better future, now, for many, federalism’s prospects have crumbled with the realization that institutional constraints on executive power via the rule of law are necessary for its success. The ruling party (CPDM in English or RDPC en français) and entrenched elites around the presidency would not survive in any system where the rule of law replaced the currently operative, rapacious law of rule by decree and the patronage system it underpins. That limits the efficacy of federal options even if they were offered, which they decidedly have never been since the last remnants of federalism were ended in 1972 by Cameroon’s first and only other president, Ahmadou Ahidjo.

The gulf between a historic assumption that a return to federalism offered a path for reconciliation and shared prosperity, and the regime’s commitment to a unitary state with begrudging elements of decentralization and special status, has narrowed room for compromise and negotiations. The radical “one and indivisible Cameroon” regime proponents have doubled down this year on their hammer-and-lies strategy, while the most radical separatists condemn and threaten any anglophone individual or group who suggest any alternative solutions or pathways to peace other than a direct road to Buea. But that is where creative and committed compromisers from all sides need to find realistic and workable processes to marginalize those two extremes. While Cameroonians must lead any process for it to be legitimate, no progress can be made without external carrots and sticks, given an intransigent regime that clings to the militarized hammer option over peace and compromise. So far, the regime has faced zero consequences even as millions suffer the immediate and long-term effects of war, displacement and continued bad governance.

With the firm understanding that internal stakeholders will be doing the heavy lifting, what follows are 10 critical observations designed to bring outsiders up to date if there is to be any hope for peace, justice and prosperity for those living incredibly difficult lives in the two anglophone regions.

1. The best, permanent solution to the anglophone crisis would be a transparent, inclusive negotiated peace process leading to a free and fair, internationally supervised referendum that included a clear question on institutional arrangements, including independence. That would solve a historical wrong committed first in 1961 under British and UN auspices, and again in 1972. It would signal an end to the political and economic marginalization perpetuated from Yaoundé. It is not a stretch to see parallels between Russia’s quick annexation “referendums” in occupied areas of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, and Ahidjo’s hastily conducted, unjust May 1972 constitutional referendum, which allowed the entire population to vote (with reported 99 per cent approval) to dismantle a federal system expressly designed to accommodate the anglophone minority. But it is also true that some of the local armed leaders on ground zero and some of the loudest, self-proclaimed leaders in the diaspora spend more time calling each other traitors than co-ordinating a united diplomatic and military front that might provide encouraging glimpses of future self-determination. Many of the most thoughtful and capable Southern Cameroonians who would ultimately prefer independence, if asked directly, worry that there are insufficient institutions in place now to constrain the power-hungry, the co-opted or the well-armed during a transition process. However, many are working hard behind the scenes to bridge divisions and propose confidence-building measures. They want to find creative ways to inch forward and educate the international community on the realities of how hard life has become, not only in the NW and SW regions, but also across Cameroon, given this government’s regime-maintenance priorities.

The main reason the government fights so hard against outright independence, federalism or even direct negotiations is that an independent or more autonomous Ambazonia, given the human and natural resources available, could potentially outshine the rest of Cameroon in either democracy or economic growth. That would weaken the CPDM’s vise grip on political and economic power, particularly the ruling family that is positioning a new generation to take over.

2. In 2022, any immediate independence option is moot. Neither African Union nor UN members, let alone the regime in Yaoundé, have any appetite to consider a process that might lead to an immediate vote for an independent Ambazonia. Even as some Amba units co-ordinate more closely and exert authority over some territory, there is no indication yet that these forces have the combat power to liberate and hold large parts of either the NW or SW and start to build an independent, empirical state modelled on Somaliland. The latter is still waiting for recognition after 30 years of offering better governance than Mogadishu’s tenuous grasp over the rest of Somalia. The reality is that independence is the best option to remove a tired, kleptocratic gerontocracy from the lives of five million or more anglophones. But diaspora leaders have spread the myth for years now that independence was just around the corner. This has weakened their legitimacy and prevented alternative, more realistic pathways to peace and justice that might ultimately include an independence option but would also provide incentives and pressures for reform across Cameroon, possibly reducing the need for complete independence. Many anglophones call cities and towns outside Ambazonia home, and a case can be made for the economic and even security benefits of keeping Cameroon whole within a federal structure. But those discussions never occur when the regime hardliners demand a one and indivisible country. Meanwhile, decades of marginalization and mistrust make it difficult for many Southern Cameroonians to contemplate any reforms that could effectively institutionalize the autonomy they desire.

3. The international community needs to accept there is a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) in Cameroon and change their approach. For years, the Cameroon government and international organizations have purposely refrained from referring to the conflict as a NIAC or civil war. Current interpretations of what constitutes a NIAC fail to capture the dynamics of the war in Cameroon and other places where the old model of one or two centralized military-political organizations fighting against a national government (think Biafra in 1967-70, or UNITA against the MPLA in Angola until 2002) offers a clear-cut definition of organized opposition. Since at least the 1990s, across Africa (and elsewhere, see Syria) the characteristics of civil war and armed rebellion only rarely follow that old model. Lack of a single hierarchy of command, which among Ambazonians is true, does not negate that there are multiple armed units fighting for the same end and which, operationally and politically, sometimes co-ordinate with other military and political groups.

This seems like a pedantic discussion for experts in the law of armed conflict, but it materially matters in terms of raising the stakes for all armed combatants to follow the basic rules of war and to allow humanitarian actors to ameliorate suffering. It also raises the stakes for international diplomacy: this civil war needs international mediation, and arms exports need to be curtailed. Importantly, the diversity of anglophone actors – semi-autonomous armed units of platoon or company size plus a multitude of domestic and international civil society groups – illustrates an instinctive pluralism that differentiates Southern Cameroonians who have always chafed against the centralized, hierarchical approach of rulers in Yaoundé. That pluralism is a feature, not a bug, and the international community needs to appreciate and accommodate it rather than condemn it.

4. Confirming basic facts in this under-reported and misrepresented conflict remains difficult, and this plays directly into the hands of the government’s strategy and narrative. There have long been calls for an independent fact-finding mission to visit the affected regions. That will have to be part of any peace process. Official government statements are often found to be incorrect. Few international journalists get into the region except when embedded with security forces, and domestic journalists face threats, arrests and physical attacks if their reports challenge the narrative of either the government or the armed groups. The same goes for local human rights activists and investigators who regularly face death threats if they report the details of an atrocity and who likely committed it. The space for international NGOs has shrunk as well. Médecins Sans Frontières has been forced to temporarily suspend operations in the SW due to insecurity as well as pressure from the government. Medical workers can be arrested if they treat wounded Ambazonian fighters, but they can be abducted by Ambazonian fighters if rumours surface they made any reports to government officials. As humanitarian needs have increased due to war and displacement, UN agencies delicately negotiate access to different areas, given the regime’s reticence to indirectly support those not completely under their control, while Amba forces suspect that international officials may be spying for the government. While there are estimates of those killed or displaced, the numbers vary widely. Exaggerations for partisan purposes undercut efforts to determine the realities on the ground. Thus, there are few authoritative sources of information that can be trusted to provide hard facts: propaganda and narrative spin overwhelm appeals to veracity. Without hard facts – including a broad assessment of the attitudes and desires of those who live on ground zero – local and international peacemakers are attempting to paddle upstream in a boat without a paddle. And they might not even have a boat.

5. Following models used throughout history, from Cameroon’s Hidden War in the 1950s-60s to South Africa as late as the early 1990s, the Cameroon government uses third-force tactics and other divide-and-rule manipulations to discredit Ambazonian opposition. This reality seems to be ignored by diplomats and international organization representatives who should know better, but the government and its security forces directly employ third-force strategies to sow confusion among Amba fighters, local civilian populations and the international community. Those strategies include covert operations as well as an extensive disinformation campaign. Given the decentralized nature of the armed struggle across the two regions, it is not always clear who is giving the orders for this attack or that kidnapping. Over the last few years, coincidentally, at those brief moments when there seems to be growing international community attention to the crisis, an apparent Amba attack on a school, church or other civilian target weakens any nascent political will among external stakeholders. The government also arms, funds, incites and then protects from prosecution a few local leaders, including chiefs. In addition, it inflames pre-existing, local conflicts between communities such as Muslim Mbororo pastoralists and Christian farmers in the NW region. The more the government can do to support its narrative of divided, squabbling “terrorists and separatists,” the easier it is for the government to ensure no substantial external pressure ever develops to incentivize a negotiated solution.

As in all armed conflicts, especially those that drag out without an endpoint in sight, some with access to weapons become less interested in political objectives and turn to more immediate, material gratifications (one has only to look at the number of washing machines that Russian occupiers have pillaged from Ukraine). Government soldiers and police set up roadblocks to generate fees and fines, while Amba groups do the same to generate taxes to support the revolution. Again, from the government’s perspective, the longer they can hold out without engaging in meaningful negotiations, the more they hope armed groups lose focus and lose civilian support. Not surprisingly, social media has provided an additional, effective conduit of weaponized disinformation. Accounts for different leaders or groups are duplicated and then filled with disinformation, including vitriolic attacks on other Ambazonian groups. WhatsApp and other communication platforms are filled with rumours and targeted disinformation designed to create information chaos and mistrust. And like apartheid South Africa after 1963, Cameroon implemented an anti-terrorism law in 2014 which allows the arrest and imprisonment of civilians who can then be tried by military tribunals. This has been used against opposition politicians, journalists and even family members and friends of suspected Ambazonian fighters. Outsiders seem to ignore history lessons about the lengths that repressive regimes will go to weaken opposition and overlook that NIAC dynamics change as they stretch out without resolution. But it cannot be forgotten that the government created the conditions for armed conflict and must be held primarily responsible for the initiation of armed repression and its continuance.

6. Even considering third-force manipulations, some Amba forces or loose-cannon individuals have committed atrocities, stolen, kidnapped, destroyed buildings and killed civilians and each other. These activities weaken local support and cause international observers to shy away from direct engagement, to the regime’s benefit. There have been efforts to educate Amba boys in the law of armed conflict and most of the better organized and effective units do not put up with their fighters engaging in these activities. Sometimes, bandits are caught impersonating fighters. But there is also a culture of never admitting mistakes or serious incidents where Amba forces are implicated, which reduces trust in the information coming from all Ambazonian sources. (Amilcar Cabral would not approve.) There have also been deep divisions in policy and strategy among Ambazonian groups around such things as school resumption or extending lockdowns (called “ghost towns” or “ghost days” locally). On Mondays in many anglophone-majority cities and towns, all businesses and other street activity close down as a silent protest against the regime, but some groups try to extend those periods around certain events. This then creates significant hardship for those trying to run a business, work or even buy food or attend to crops. Civilians are then caught between different Amba groups demanding adherence to different ghost days, and regime officials and security personnel who may punish those who don’t open their businesses.

Thus, with banditry, third-force manipulations, tactical mistakes, lack of discipline or the Amba units’ own bad policy direction, residents in the two regions have sometimes turned against local Amba boys but without concurrently moving back towards regime support. Five years of admonishments from regional governors, district officers and military commanders for local people to work more closely with officials and security forces to root out Amba “terrorists and separatists” mostly fall on deaf ears, an important signal somehow ignored by those regime officials and the international community.

7. The Cameroon government has been able to pursue its hammer-and-lies strategy largely due to uninterrupted international financial bailouts since 2017 and continued military support. In the mid-2010s, Cameroon started building or refurbishing stadiums to host the African Nations Cup in 2019, largely using borrowed money (the stadiums were, unsurprisingly, not completed in time and Egypt stepped in to host). This occurred during a slump in oil and gas prices, leading to macroeconomic distress. In mid-2017, the IMF provided a three-year emergency credit package. After COVID-19 hit, Cameroon received additional financial packages from the IMF and development banks and even floated some sovereign bonds. During that period, military spending – imports including weapons and ammunition, armoured vehicles, helicopters, plus significant recruitment and base expansions – rose dramatically, in addition to the DDR program launched in late 2018 but still struggling in 2022. While some countries have rolled back their military support and exports to the Biya regime due to human rights abuses, that has been limited and selective. Cameroon continues to promote the idea that military training and exports provided by its international partners help the fight against terrorists, including Boko Haram in the far north. But since early 2018, Cameroon’s security forces have shifted significant personnel and capabilities south against Ambazonian groups and left most of the fight against Boko Haram to the Nigerians and Chadians. Sadly, the regime can count on apathy and ignorance in the international community as they paint all armed opposition with the same brush.

8. Fundamentally, the core of the hammer-and-lies strategy rests on a bigger lie: the selective privileging of some constitutional principles over others despite an absence of constitutionalism. Government hard-liners and some constitutional scholars and media pundits regularly repeat the “one and indivisible Cameroon” mantra as justification for armed suppression of those who demand any significant change to the “decentralized unitary state” (phrases both included in Article 1.2 of the Cameroon Constitution). But Cameroon from 1961 was a federal system, at least in name, until 1972. The irony here is that constitutionalism in the country is historically weak and selective – which accounts for Biya’s 40 years in power – and yet certain elements of the constitution are held up as inviolable. For example, Article 64 states that “No procedure for the amendment of the Constitution affecting the republican form, unity and territorial integrity of the State and the democratic principles which govern the Republic shall be accepted,” which keeps secession and probably federalism off the table. But both Art. 64 and Art. 1.2, among other clauses, also refer to democratic principles and equality before the law. For the regime, “one and indivisible Cameroon” represents the hammer in speech form, a stance from which compromise is impossible. Concurrently, however, most (Southern) Cameroonians just want democratic principles and equality before the law in practice, and thus can be seen to be demanding, and in some cases fighting for, a different set of already existing constitutional principles.

9. Regime change is coming in Yaoundé regardless of what happens in the anglophone regions. Biya is 89 and rarely seen in public. He and others are grooming his son, Franck, to replace him, but other elite factions have alternative plans for a post-Biya Cameroon. Cameroonians and external stakeholders need to be prepared to leverage a transition period to build a foundation for peace and democracy. Some say a non-military solution to the anglophone crisis is possible only when Biya is gone, but a regime change hardly guarantees a non-military path is taken (or that new security partners are not brought in to escalate military efforts). The more preparation is done now before any transition process begins, the better the chances that a rare, critical juncture moment can work for peace.

10. Last, if the Western international community – including the U.S., Canada, Norway and the European Union – have learned anything from Mali and Burkina Faso, they cannot let France take the Western lead on Cameroon. There is broad belief across Cameroon that France pulls the Biya government’s strings, or at least has outsized influence on the government’s decisions and actions. In anglophone regions, distrust of the French is even greater. There is, of course, significant French influence in the country, but Cameroon’s government has become deft in the art of insulating itself from too much dependence on any single foreign benefactor. Large-scale Chinese, British, American and Russian investments in ports, mining, oil and natural gas provide a cushion against the French, while Cameroon’s enduring commitment as a logistics hub for UN peacekeeping missions makes it an invaluable regional security partner.

It is true, then, that it is easier for the international community to downplay the civil war in Cameroon for all sorts of short-term economic and security interests. But as is becoming clear across Africa and Europe, short-termism can create bigger problems eventually. And France’s unique interests in Africa do not align easily with other Western countries: France’s African diplomacy under President Emmanuel Macron appears increasingly tone deaf and designed to generate animosity among the masses while it attempts to ingratiate itself with a narrow stratum of African elites. Macron visited Cameroon in July 2022 and offered his support to the Potemkin decentralization being implemented by Yaoundé. Then, in September 2022, Macron appointed Gen. Thierry Marchand, head of the Directorate of Security and Defence Cooperation, who happens to have extensive experience in military training and operations across Africa, the new French ambassador to Cameroon. France is not signalling it wants to be part of solving the anglophone crisis. Letting France or any single country take the Western lead on Cameroon contributes to a worsening longer term outcome.

The Time for Peace Was Yesterday

There needs to be concerted, co-ordinated Western action on Cameroon if peace is ever going to have a chance. With the Swiss process set aside, Western governments can no longer sit back and say, “let the existing process work.” Diplomats and other external stakeholders should just listen to the voices of those most affected in terms of whom they might trust and the mechanisms that might work to generate a constructive process. Fighting would stop almost overnight if a serious, transparent process were in place which also kept security forces in their barracks.

Helping Cameroonians end the senseless violence, suffering, displacement, schooling disruption and endless destruction of homes, schools, businesses and churches will not be easy. But the reality is, after five years, there has never been any international political or economic pressure on the regime to adjust its hammer-and-lies approach to the anglophone crisis. No African government, African or non-African elder statesperson has stepped up to offer their services to mediate the civil war. But there are countless activists inside and outside the country who have worked tirelessly to raise the conflict’s profile, to engage in peacebuilding activities, to build mechanisms to facilitate bridge-building across factions and to try to work within a political system that is designed not to work. Their clarion call is always “why has the international community forsaken us?” and that was years before Russia invaded Ukraine. Now, Western governments either admit support for the hammer-and-lies strategy of a tired, kleptocratic regime, or they will finally recognize their culpability and stop enabling that strategy. They can then find and work with those who truly desire peace via a political settlement, and then cultivate an environment for peace, democracy and prosperity to sprout.

Culled from Canadian Global Affairs Institute