Neocolonialism spurs ongoing crisis in Cameroon

In October 2019, Nebane Abienwi, a 37-year-old Cameroonian man, died in ICE custody in San Diego. Abienwi was one of at least 10,000 Cameroonians seeking asylum in the United States. The recent increase in Africans being detained at the U.S.-Mexico border is largely a result of this exodus of people from Cameroon.

Many factors are causing heightened emigration from Cameroon, perhaps the primary one being the “Anglophone crisis.” Since 2016, there has been significant unrest and government repression in the western English-speaking (Anglophone) regions of Cameroon. Much of the media coverage has depicted protesters in the western regions as fighting to defend their “Anglo-Saxon heritage.”

Of course, Cameroon is a West African country. Its peoples’ histories date back thousands of years, the vast majority of which were lived without the exploitative presence of British colonialism. So why in 2019, nearly 60 years after Cameroon’s official independence, is British “heritage” given so much consideration in this West African nation?

Cameroon: 1884 to the present

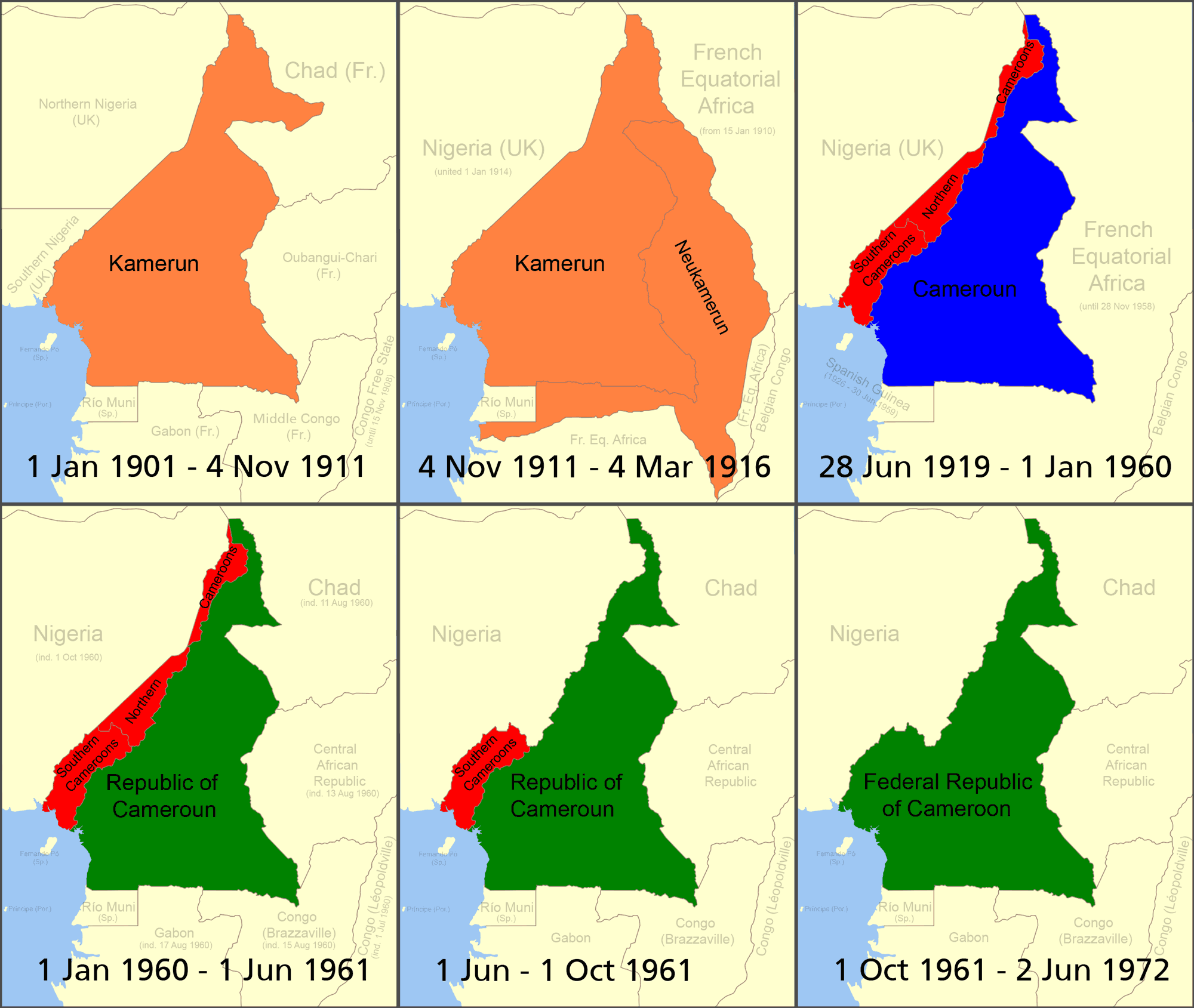

Cameroon’s changing boundaries. Orange=German Kamerun, Red=British Cameroons, Blue=French Cameroun, Green=Republic of Cameroon. By Roke – Self-made based on public domain CIA map Image:Cameroon Map.jpg, original svg file located here., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=938868

To understand the current climate in Cameroon, one must understand its history. Germany claimed Cameroon as a colony in 1884 in the wake of the Berlin Conference, in which the major colonial powers of the time met to arbitrarily carve up the lands of Africa amongst themselves, without consideration for the desires of the incredibly diverse populations of Africa.

However, Germany’s control over Cameroon was short-lived. As capitalism entered its imperialist phase towards the turn of the 1900s, competition increased between the European powers over control of the various colonized nations, culminating in World War I. In 1919, after defeating Germany in WWI, France and England took possession of Germany’s colonies in the Global South, clearly revealing the inter-imperialist character of the war.

Cameroon — its borders already artificially constructed after the Berlin Conference — was once again arbitrarily reshaped. England took control of the smaller western regions of the country, and France claimed the eastern regions. As the 20th century progressed, like in most African nations, a national liberation movement developed in Cameroon. The movement was led by the Union of the Populations of Cameroon. The UPC led an armed struggle on the platform of national reunification and radical social proposals such as land redistribution, increased salaries for workers, and universal education.

In an attempt to undermine these growing, militant and principled movements, France strategically “granted” its many African colonies independence in 1959. In 1960, Cameroon and 12 other former French colonies were officially made independent. Far from an act of kindness, this was a strategic decision by France to install neocolonial governments in their former colonies — administrations that kept their nations’ people and resources subservient to French interests but led by native elites to present the appearance of national sovereignty.

In Cameroon, France appointed career politician Ahmadou Ahidjo as president. In a 1958 speech, Ahidjo described his allegiance to France, the nation that had exploited his own people for the past 40 years: “How can we conceive having any other partner than this country we know and love? How can we forget its accomplishment all these years that we have learned to understand and appreciate her. … ” (Takougang and Krieger, African State and Society in the 1990s, 1998) In collaboration with French military and intelligence agencies, Ahidjo’s government brutally crushed the UPC movement.

The English-controlled western regions were also granted independence in 1960. Part of the territory voted to join Nigeria, and the other part voted to join Cameroon. The French- and English-speaking regions of Cameroon designed a federated constitutional arrangement, and the English-speaking elites were folded into Ahidjo’s single-party administration. National reunification was at least partially achieved in 1961, but not in the manner the UPC and its supporters envisioned. When independence is granted and not won, it is done so on the terms of the colonizing powers.

In its 60 years of nominal independence, Cameroon has had two presidents: Ahidjo and Paul Biya, the current president. Both men were born in the French-speaking region of Cameroon, and both have maintained a subordinate position to France and the West more broadly. Major local industries are still owned and controlled by European interests.

For example, Cameroon’s largest export by far is oil. While there is a state-owned oil company in Cameroon, two of the largest and most profitable oil companies in the country, Total E&P and Perenco, are based in France (and Perenco is a Franco-British joint project). Perenco is the largest oil producer in Cameroon, while Total E&P is the largest distributor of finished petroleum products.

Additionally, after accepting an International Monetary Fund loan in 1988, Biya’s government bent to the West’s will to an even greater degree and implemented a Structural Adjustment Program, which included significant cuts to Cameroon’s national budget and the privatization of many “parastatal” companies (Takougang and Krieger, 1998). Finally, France still controls Cameroon’s currency and treasury.

Neocolonialism, neoliberalism, and the Cameroonian elite’s complicity in the continued exploitation of the Cameroonian masses have led to high inequality and low standards of living in much of the country.

Popular uprisings since the 1990s

In addition to neoliberal austerity and economic hardship, a major point of discontent in Cameroon has been the governance of the country, under both Ahidjo and Biya. Both have been criticized for altering the political structures of Cameroon to consolidate their own power, and for engaging in tribalism. Perhaps the most notable example was when Ahidjo’s government abolished the office of vice president in 1982. This angered some in the western English-speaking regions of Cameroon because as part of the country’s constitutional reunification agreement, the office of president was to be designated for a “Francophone” and vice president for an “Anglophone.”

Class society is always on uneven footing, and Cameroon erupted in the 1990s. A massive student movement broke out in 1991, and later that year, up to 2 million people participated in a tactic called “villes mortes/ghost towns” (similar to a general strike) to bring four provinces — two English-speaking and two French-speaking — to a grinding halt for months (Takougang and Krieger, 1998).

Some of the discontent was channeled into a growing “Anglophone” nationalist movement, which included organizations such as the Cameroon Anglophone Movement and the All Anglophone Conference. The government met these movements with both the carrot and the stick in an attempt to subvert their momentum: certain concessions, such as the introduction of multiparty elections in 1992, on one hand, and heavy repression, on the other. Eventually, the mass protest movements waned as the 1990s progressed.

Street of Buea (SW Region Cameroon) on a Ghost town day, 2016. Photo: DrAgach, CC-BY-SA-4.0

Since 2016, mass protests have again emerged in the two English-speaking regions that helped anchor the ghost towns movement in 1991. This time, the protests have been mostly defined by their “Anglophone” character. They were sparked when teachers and lawyers in the two English-speaking regions went on strike to protest the appointment of French-speaking judges and teachers and the use of French documents in courts, with “no understanding of the common law and educational systems that operate in these areas.”

Ghost towns have once again become a popular tactic. An armed secessionist movement has also emerged, declaring the “Anglophone” regions of Cameroon to be a nation named Ambazonia. Economic crisis, mass arrests, repression of protests, and government clashes with armed militants have caused at least 2,000 deaths and displaced thousands more. The ramifications of this situation reach as far as the U.S.-Mexico border.

Colonialism is relationship of exploitation, not heritage

The elephant in the room is that colonialism is a relationship of exploitation, not heritage. While it may be true that President Biya has consolidated state power in the hands of his “Francophone” party and has mostly stacked government positions with French-speaking administrators, it is also true that Cameroon ranks near the bottom in global quality of life measurements. Poverty afflicts millions of people in Cameroon, regardless of which colonial language they speak.

Since the French installed Ahidjo and crushed the popular anti-colonial UPC movement, political life has largely been a playground of the elite in Cameroon. Even prominent “opposition” political leaders that emerged in the unrest of the 1990s, such as Samuel Eboua and Adamou Njoya, were former administrators in President Adhidjo’s government (Takougang and Krieger, 1998).

When Western and Eastern Cameroon agreed to reunify in 1961, the “Anglophone” elites brokered a deal to be absorbed into Ahidjo’s party and government — some with leadership positions, including the guarantee that an “Anglophone” would always hold the vice president’s office. Throughout the following decades, this power-sharing agreement between elites gradually eroded, with the “Anglophone” elites largely stripped of their influence. The colonial-inspired sectarian division of “Anglophone” versus “Francophone” misdirects the justified anger of the Cameroonian masses towards a battle that ultimately benefits the elites.

Additionally, while there is certainly an element of tribalism in Cameroon, the protest movements vary ideologically. For example, The Stand Up for Cameroon movement is a coalition of political parties and organizations — each with strengths and shortcomings — that are united against tribalism and in their calls for political transition in Cameroon. To reduce the ongoing conflict in the country to “Anglophone” versus “Francophone,” as many have, is inaccurate and characteristic of the racist trope that reduces conflict in Africa to an irrational tribalism, rather than tangible contradictions.

Strong movements rooted in national unity have precedent in Cameroon and reveal the political frailty of tribalism. The UPC became a force in the 1950s with its program of national liberation, reunification, and radical economic redistribution. In Cameroon’s first multiparty presidential elections in 1992, John Fru Ndi, the Social Democratic Front party’s candidate, won major support in both “Anglophone” and “Francophone” regions with a program that spoke to peoples’ widespread concerns. Many believe that Biya only won the 1992 election due to fraud.

As President Biya approaches 90 years of age and protests continue, Cameroon’s political future is unclear. However, history shows that only a movement that speaks to the root causes of the challenges that people are facing, rather than to the manufactured issue of colonial heritage, will be able to effectively energize a critical mass of Cameroonians to liberate the country from the strings of neocolonialism and capitalism.

Source: Liberation News