Factional struggle conceals imperialist interests in Cameroon

In the aftermath of recent elections in Cameroon, instability has increased, with a factional struggle opening up between different sections of the ruling class. President Paul Biya of the ruling CPDM, who retained power in 2018, has ramped up political repression, arresting opposition leader Maurice Kamto and intensifying his suppression of the country’s Anglophone minority.

All of this is taking place against a backdrop of general decrepitude for Cameroonian society, which is suffering from years of underinvestment, slowing economic growth and widespread decay. Meanwhile, Biya and Kamto (both of whom are cut from the same bourgeois cloth) are increasingly leaning on different sets of imperialist powers, as China is starting to muscle into territory formerly wholly dominated by Western imperialism. The former Defence Minister, Edgar Alain Mebe Ngo’o, was also detained today (6 March) as part of this spat within the ruling class.

The Biya regime has been a loyal ally of Western (and particularly French) capitalism since taking power in 1982. In recent years, Biya has also been a military ally of the United States against the Islamic terror group, Boko Haram. However, Cameroon is also an important country from the perspective of Chinese imperialism. It is a key part of Beijing’s One Belt, One Road project in Central Africa. As such, China is beginning to extend its influence in Cameroon (as in neighbouring Nigeria).

China’s presence means Western imperialism is pushing back against it by simultaneously pressuring Biya to keep his distance from Beijing, and by supporting other elements in the ruling class. Biya is trying to balance between different imperialists, while Kamto is seeking to make himself more attractive to the West by offering his services against Biya. In spite of all of his anti-regime demagogy, however, Kamto is not seen as a genuine political alternative by Cameroonian workers and peasants.

Cameroon’s capitalist malaise

The masses in Cameroon are suffering immensely, and it seems there is no way out. The Anglophone crisis (which threatens to erupt into a full-blown civil war) is just the latest expression of long-term degeneration of volatile and degenerate Cameroonian capitalism.

Cameroon is a weak, oil and mineral-based export economy, which has been feeling the slowdown in world trade and the Chinese economy: two key factors that previously kept oil and mineral prices up. While the country’s debt-to-GDP hovered around 10-12 percent until 2014, it has now shot up to 35.7 percent, after oil prices dived in 2014.

The masses in Cameroon are suffering, and it seems there is no way out. Biya and Kamto are cut from the same cloth / Image: Robert Prince

The increased debt is also limiting Biya’s room for economic maneuvers. To meet the terms of new IMF loans, Biya has carried out austerity, including a reduction of government spending from 8 percent to 6.6 percent of GDP from 2016 to 2019. Schools, hospitals and infrastructure are in a chronic state of under investment. Meanwhile employment rates are stagnant and so is development in production (70 percent of Cameroon’s working population is still employed in the low-tech agricultural sector).

The ruling class is far more interested in reaping super-profits from the oil industry than in investing in actual production. All the while, the parasitic Cameroonian bourgeoisie and political elite spend billions made via corrupt deals on private jets and palatial accommodation (usually abroad). Billions more are lost to so called “capital flight”; which, in this context, simply means open theft of public funds.

In order to stabilise his rule, Biya has covered his austerity with anti-Anglophone nationalist hysteria, and his cuts disproportionately target the Anglophone regions of Cameroon. These nationalist attacks have in turn fueled a separatist crisis. Despite being the source of most of Cameroon’s wealth, the oil-rich Anglophone regions are made to swallow the deepest cuts, on top of social and political repression. And more austerity is likely to be on the way, as creditors such as the IMF, wary of the state of the economy, are demanding even more cuts in the 2019 budget.

All these factors have contributed to the pauperisation of the Cameroonian working class. Despite a small increase in GDP growth in 2018 (3.8 percent versus 3.5 percent in 2017), population growth has meant that about 30 percent of Cameroonians remain in poverty, while Biya, Kamto and their cronies in the ruling class grow fat.

China encroaches

The main factor in the recent political struggle between Biya and Kamto is the increasing presence of Chinese imperialism in Cameroon. Beijing is coming to regard Cameroon as a key African foothold, especially because the country is not seen by US imperialism as fundamental to its sphere of influence. Sino-Cameroonian trade has increased tenfold in a decade, China is now Cameroon’s biggest export partner after France, and it dominates the Cameroonian construction and infrastructure sectors.

Beijing is clearly attempting to court Biya and pull him away from the West. He was invited for a three-day state visit to China in March 2018, and visited Beijing again in September at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, where President Xi Jinping pledged a $60bn package of aid, investment and loans to Cameroon. Meanwhile, Beijing has forgiven $174m of Cameroon’s debt between 2007 and 2019. This bribe is only a tiny sliver of the approximately $3bn Cameroon owes to China, which shows how Chinese finance capital has begun to creep into the void left after France decreased its engagement with its former colony.

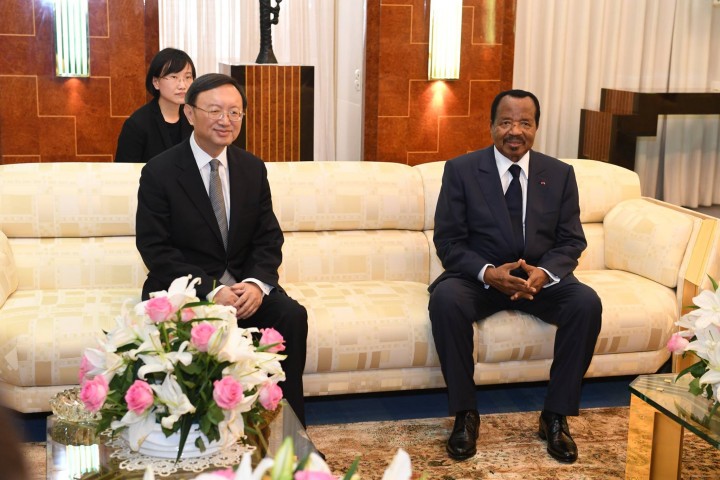

The main factor in the recent political struggle between Biya and Kamto is the increasing presence of Chinese imperialism in Cameroon, which is starting to lean on Biya / Image: fair use

The string of debt write-offs are actually on loans obtained to fund construction by Chinese companies in Cameroon, meaning Beijing is subsidising its own development projects: a small price to pay for a major African foothold. China has been using its financial muscle throughout Africa, taking key assets and infrastructure as collateral when countries are not able to repay their debt. Of course, if it is up to China alone, Cameroon will not escape this fate.

China has also been exploiting Cameroon’s rich gold reserves for the past several years, often illegally, and utilising methods that destroy surrounding farmland and leave behind trenches that cause fatal accidents and trigger landslides. This has resulted in a huge amount of anger and resentment from the population. The Forests and Rural Development Association (FODER) in Yaounde claims that the Biya regime has been sending in the army to protect Chinese mining companies from enraged locals.

The nations’ relationship reached a watershed in 2011 when China committed billions of dollars to finance a new sea port in the fishing town of Kribi. When completed in 2035, it will be the biggest deep-water port in the region. This investment shows Cameroon’s strategic importance to Beijing’s ambitions in Africa. The Kribi port will extend the reach of the so-called New Silk Road: that is, China’s plans to construct an international trade network based on Beijing’s interests.

Kamto: wannabe Western lackey

With Biya drifting closer to China, the West is trying to defend its own position. It is therefore leaning on other forces within the Cameroonian ruling elite. Kamto (who came second in the presidential elections, with around 14 percent of the official vote) has been offering his services to the West. But he lacks any real support on the ground. As part of this factional struggle within the ruling class, Kamto was arrested by Biya’s troops on 28 January. He is now being held at the Special Operations Unit in Yaoundé, from which he sent a message criticising the Biya government for his “illegal and arbitrary” detainment. Despite this language of martyrdom, Kamto is a consummate opportunist, and until 2011 he was actually Biya’s Minister for Justice in the CPDM. He is made of the exact same stuff as the sitting president. The Cameroonian masses are not blind to this. This was underlined by the fact that attempted protests against Biya’s re-election and Kamto’s imprisonment have been complete flops.

While Western imperialism does not currently see Kamto as a convincing replacement for Biya, he is still a potentially useful pawn

Kamto thought he could demagogically unite the weak and atomised opposition parties of Cameroon (of which there are over 200) under the single, “anti-Biya” banner of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (CRM). Aside from a vague promise to resolve the Anglophone crisis with “dialogue”, the CRM’s political programme was little different from that of the CPDM. It also included a number neoliberal policies Kamto hoped would appeal to Western imperialism, including the need for more “flexible” labour and “modernisation” of the economy (i.e casualisation of labour and privatisation). Kamto also probably thought that his friends in the West would position him as Biya’s successor and see him as a trustworthy ally, given the president’s drift towards China and Kamto’s esteemed status as a former chairman and special rapporteur with the U.N.

He was mistaken. The US did not do much to support the CRM, while France continued to back its traditional party. Biya’s victory was never actually in question, especially with the Anglophone separatists enforcing a voting boycott, which resulted in an extremely low turnout by English-speaking voters (who tend to be most critical of Biya). Western imperialism is not seeking regime change in Cameroon. As it stands now, they are merely trying to maneuver to get more concessions from the existing regime.

The Anglophone crisis continues

While all this is going on, Biya’s heavy-handed approach is turning the Anglophone crisis into an uncontrollable conflagration. More than 430,000 people have been displaced and hundreds killed over the course of the conflict, with reports of atrocities by both the separatists and Biya’s Special Forces.

Neither China nor the West want this situation to get out of hand. They would all prefer stability. But while China and France have been relatively silent about the affair, the US has threatened to pull military support, training and equipment from Cameroon. Laughably, General Thomas D. Waldhauser, leader of United States’ Africa Command, claimed this was due to Biya’s “atrocities”. But the US has never batted an eye at Biya’s political repression up until now, and this new measure is probably another attempt at putting pressure on Biya.

The West is also using the arrest of Kamto as part of this game. The U.N. Secretary General and the International Law Commission have threatened that Kamto’s “continued detention will lead promptly to a comprehensive reevaluation of U.S. military and other assistance to the Cameroonian government.” Meanwhile, the EU (via its mouthpiece in Cameroon, Federica Mogherini) condemned the “arrest and prolonged detention of several leaders of an opposition party, including its leader Maurice Kamto”. The statement calls for an end to “human rights violations in the north-west and south-west regions of Cameroon… through an inclusive political dialogue and in a context of respect for fundamental freedoms and the rule of law.” It ends with a subtle threat, referencing “the foundation for the partnership between Cameroon and the EU, for the benefit of all Cameroonians” being based on these ‘values’ and concluding “the EU will support any initiative in this direction” (my emphasis).

While Western imperialism does not currently see Kamto as a convincing replacement for Biya, he is still a potentially useful pawn. By portraying their old ally Biya as a bogeyman building up Kamto as a martyr, they could try to lean on him to balance Chinese interests, and keep their options open in terms of succession when the 82-year-old incumbent is finally off the scene.

The masses need an alternative!

Cameroonian capitalism is rotten to its core. It is incapable of showing any way forward for the poor workers and peasants of the country. But although Biya’s decrepit, 37-year regime is long overdue to be overthrown, Kamto is no alternative. He represents the same system and the same ruling class as Biya. This explains why the masses have yet to enter the scene: they do not see anyone offering solutions to the dire social problems in Cameroon, and do not trust any of the political representatives on offer. Between the imperialist tug-of-war and squabbles within the ruling class; the working class and poor can only lose out.

A radical revolutionary movement, organised on class lines against the ruling elite and imperialism, is the only way forward

At the same time, there is no real workers’ party and no real labour movement, unlike over the border in Nigeria. The last major strike (prior to the teachers’ walkout by Anglophones in 2017) was in 2008, and even that wasn’t led by the feeble Confederation of Cameroon Trade Unions – it was a grassroots action led from below. In these conditions, along with the general economic decline, the stage is taken over by different imperialist forces, along with opposing sections of the degenerate, parasitic bourgeoisie, who have no issue with wreaking havoc in the country to pursue their own narrow interests.

What is needed is a radical revolutionary movement, organised on class lines, to unify the Francophone and Anglophone working class and poor around social demands against the Biya regime and the rest of the rotten ruling class. Beyond that, it is necessary to build a workers’ party that will channel the desire for change into a programme of action. This is the only way forward.

Source: Marxist.com