COVID-19: Biya faces rising criticism over his public absence

The coronavirus pandemic could narrow one gaping inequality in Africa, where some heads of state and other elite jet off to Europe or Asia for health care unavailable in their nations. As countries including their own impose dramatic travel restrictions, they might have to take their chances at home.

For years, leaders from Benin to Zimbabwe have received medical care abroad while their own poorly funded health systems limp from crisis to crisis. Several presidents, including ones from Nigeria, Malawi and Zambia, have died overseas.

The practice is so notorious that a South African health minister, Aaron Motsoaledi, a few years ago scolded, “We are the only continent that has its leaders seeking medical services outside the continent, outside our territory. We must be ashamed.”

Now a wave of global travel restrictions threatens to block that option for a cadre of aging African leaders. More than 30 of Africa’s 57 international airports have closed or severely limited flights, the U.S. State Department says. At times, flight trackers have shown the continent’s skies nearly empty.

Perhaps “COVID-19 is an opportunity for our leaders to reexamine their priorities,” said Livingstone Sewanyana of the Foundation for Human Rights Initiative, which has long urged African countries to increase health care spending.

But that plea has not led to action, even as the continent wrestles with major crises including deadly outbreaks of Ebola and the scourges of malaria and HIV.

Spending on health care in Africa is roughly 5% of gross domestic product, about half the global average. That’s despite a pledge by African Union members in 2001 to spend much more. Money is sometimes diverted to security or simply pilfered, and shortages are common.

Ethiopia had just three hospital beds per 10,000 people in 2015, according to World Health Organization data, compared to two dozen or more in the U.S. and Europe. Central African Republic has just three ventilators in the entire country. In Zimbabwe, doctors have reported doing bare-handed surgeries for lack of gloves.

Health experts warn that many countries will be overwhelmed if the coronavirus spreads, and it is already uncomfortably close. Several ministers in Burkina Faso have been infected, as has a top aide to Nigeria’s president. An aide to Congo’s leader died. For most people, the new coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms.

“If you test positive in a country, you should seek care in that country,” the head of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. John Nkengasong, told reporters Thursday. “It’s not a death sentence.”

In Nigeria, some worried their president might be among the victims. Long skittish about President Muhammadu Buhari’s absences from public view, including weeks in London for treatment for unspecified health problems, they took to Twitter to ask why he hadn’t addressed the nation as virus cases rose.

Buhari’s office dismissed speculation about his whereabouts as unfounded rumor. When he did emerge Sunday night, he announced that all private jet flights were suspended. International airports were already closed.

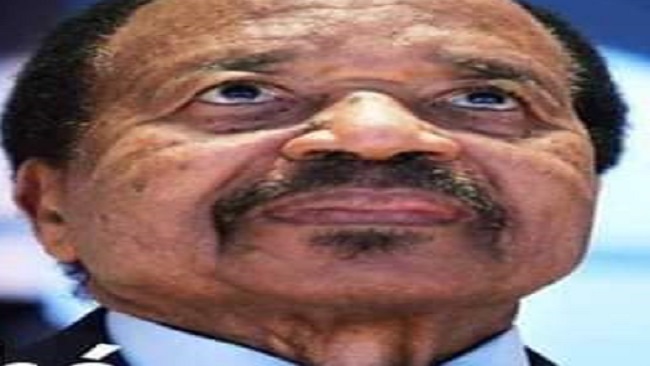

An even more frequent overseas traveler, Cameroon’s 87-year-old leader, President Paul Biya, faces rising criticism over his public absence since the virus spread to his country. Cases in Cameroon leapt Friday to over 500, the second most in the sub-Saharan region after South Africa.

While travel restrictions have grounded the merely wealthy, political analyst Alex Rusero said a determined African leader probably could still find a way to go abroad for care.

“They are scared of death so much they will do everything within their disposal, even if it’s a private jet to a private hospital in a foreign land,” said Rusero, who is based in Zimbabwe, whose late President Robert Mugabe often sought treatment in Asia.

Perhaps nowhere is the situation bleaker than in Zimbabwe, where the health system has collapsed. Even before the pandemic, patients’ families were often asked to provide essentials like gloves and clean water. Doctors reported using bread bags to collect patients’ urine.

Zimbabwe’s vice president, Constantino Chiwenga, departed last month for unrelated medical treatment in China, as the outbreak eased in that country. Zimbabwe closed its borders days later after its first virus death.

Chiwenga has since returned — to lead the country’s coronavirus task force.

But some in a new generation of African leaders have been eager to show sensitivity to virus-prevention measures.

The president of Botswana, Mokgweetsi Masisi, initially defied his country’s restrictions on travel by government employees to visit neighboring Namibia for its leader’s inauguration. But he entered self-quarantine and now reminds others to stay home, calling it “literally a matter of life and death.”

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa announced he had tested negative, just ahead of a three-week lockdown in Africa’s most developed country. Madagascar President Andry Rajoelina has as well.

Other leaders, including Burkina Faso President Roch Marc Christian Kabore and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, have tweeted images of themselves working via videoconference as countries encourage people to keep their distance.

While African leaders are more tied to home than ever, their access to medical care is still far better than most of their citizens’.

In Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, medical student Franck Bienvenu Zida was self-isolating and worried after having contact with someone who tested positive.

The 26-year-old feared infecting people where he lives, but his efforts to get tested were going nowhere. In three days of calling an emergency number to request a test, he could not get through.

Source: AFP