Barrister Tamfu-Francophone Gendarmes Affair: Yaoundé orders inquiry

Secretary of State for Defence in charge of the National Gendarmerie, Galax Etoga, has ordered a judicial investigation into an incident involving barrister Richard Tamfu. This directive was outlined in a memo issued by Colonel Pierre Aimé Bikele, commander of the Littoral Gendarmerie Legion.

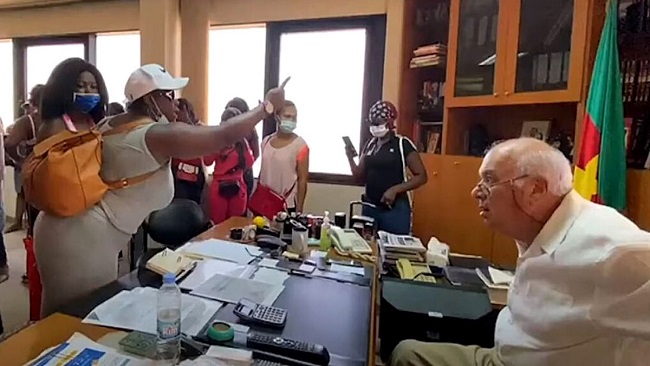

A short video recorded on November 27 in Douala shows a gendarme kicking Richard Tamfu as onlookers shout in protest. The video has sparked widespread outrage.

Galax Etoga has tasked the commander of the Littoral Gendarmerie Legion with hearing all parties and witnesses who could shed light on the incident. The investigation must be completed within 72 hours.

Since the incident, Richard Tamfu has refrained from publicly sharing his account, stating only that he was responding to a summons. He claims the gendarmes acted as if they were enforcing an arrest warrant. According to his associates, the lawyer was performing his professional duties when he was forcibly taken. Tamfu was reportedly hospitalized following the assault.

This episode comes as a blow to the SED, which recently relaunched a campaign against torture within the ranks of the gendarmerie.

Reaction from the Bar Association

The Cameroon Bar Association responded swiftly. In a statement released on November 28, its president, Mbah Eric Mbah, said:

“While awaiting a meeting of the Bar Council in the coming hours, the Bar President has instructed the Human Rights Commission and the Bar representatives in the Littoral Region to gather all relevant facts about this excessive incident, so the Bar Council can decide on the appropriate actions.”

The video has drawn condemnation from opposition politicians and public figures. The Social Democratic Front (SDF) described the incident as “inhumane and unacceptable.” SDF President Joshua Osih called for swift and exemplary sanctions, stating on Facebook: “The senior leadership of the National Gendarmerie must act immediately against the perpetrators of this medieval savagery.”

Maurice Kamto, leader of the Movement for the Renaissance of Cameroon (MRC), criticized the systemic issues behind such incidents.

“This act speaks volumes about the training of law enforcement and judicial police officers in our country, as well as the inability or unwillingness of magistrates to effectively oversee their work,” Kamto remarked on social media.

Source: Sbbc