Cameroon’s Paul Biya on shaky ground

The spiraling crisis in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions has tarnished President Paul Biya’s reputation in the West as an arbiter of stability in tenuous central Africa and could threaten his long hold on power.

The group of Cameroonians meeting under the blazing sun in Germany represents both sides of the divide in the conflict between armed Anglophone separatists and the country’s Francophone-dominated government.

The women are preparing the fish and meat for the men to barbecue, while a football tournament kicks off nearby. The French- and English-speaking guests at the annual get-together in the city of Bonn of Cameroonians living across Germany chit-chat with ease.

“We get along with each other well. It’s a friendly community – it’s a family community. There is no problem at all,” Tambi Tabong, a physician who heads the Cameroonian Community in Bonn, tells DW.

In the predominantly English-speaking north- and south-west Cameroon – home to around five million people – the picture is very different. Protests by the Anglophones who complained of being marginalized by the Francophone-led government spilled over into violence in 2016 that has escalated since.

Around the barbecue in Bonn, heritage aside, concerns over the escalating violence back home and criticism of the leadership of Paul Biya – Cameroon’s the president for 36 years – are shared.

Tabong says he is scared to return home to Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest Region, and one of the worst-affected areas.

“For me, it’s sad. We have been hoping and praying for change for a long time now, but we have the same status quo. Everyone who is reasonable wishes for change in Cameroon,” he tells DW.

The Anglophones and Francophones alike complain about Biya’s leadership.

“He has been in power because people [around him] want to keep him for personal gains,” says Jean Paul Brice Affana, a Bonn-based Cameroonian environmental activist.

“If Paul Biya had decided to run again for another term, it’s not because he wanted it. He is old. If you see him, he is old and tired,” he tells DW,

Affana was born six years after Biya came to power. His view that the Yaounde government has lost touch with the people — especially the youth – is shared by many Cameroonians.

Demonstrators called for “national unity” when President Paul Biya addressed the UN General Assembly in New York in September 2017

Demonstrators called for “national unity” when President Paul Biya addressed the UN General Assembly in New York in September 2017

What are the critical issues?

• The UN says 200 civilians have been killed in Anglophone regions since October 2017, while hundreds remain missing

• 3.3 million Cameroonians need urgent humanitarian assistance

• In the Far North Region, one out of every three people is facing emergency levels of food insecurity

• The unemployment rate was at 4.20 percent in 2017

• Cameroon is one of the most corrupt African countries, according to Transparency International

Paul Biya, a unique dictator?

Unlike other autocratic leaders in Africa who take a more “hands-on” leadership approach, Biya is known for his “hands-off” style of rule. Like many Cameroonians, Affana notes that Biya uses public funds in the country with a high poverty rate to sustain a bureaucracy of 65 sycophantic ministers and state secretaries. He mostly governs by decree or with the help of laws rushed through a rubber-stamp parliament.

“When you’re a president you have everything and everyone at your disposal and the resources to control,” James Arrey, a professor at the University of Bamenda told DW.

“Since you have everything, then you gain the loyalty of all that matters in the society. That’s how Paul Biya has managed to lead the central African nation for more than three decades.”

Research supported by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) shows Biya has spent at least four-and-a-half years in total on private trips in the 36 years he has been president. Over the same period, official trips add up to one year.

In 2006 and 2009 alone, Biya spent a third of his time outside of the country. Most of his trips have been to Switzerland, where he has made himself at home in Geneva’s five-star Intercontinental Hotel, according to the OCCRP.

His regular entourage includes his wife and up to 50 aides, according to the OCCRP, which estimates the total hotel bill and chartered jet costs at around $182 million (€156 million).

By contrast, the average Cameroonian earns $1,400 annually, World Bank figures show.

A book on Cameroon’s First Lady Chantal Biya, titled: “The belle of the banana republic: Chantal Biya, from the streets to the palace,” led to a jail term for author Bertrand Teyou.

A book on Cameroon’s First Lady Chantal Biya, titled: “The belle of the banana republic: Chantal Biya, from the streets to the palace,” led to a jail term for author Bertrand Teyou.

What do separatists want?

• At first, Anglophones peacefully raised their grievances – over the use of French in schools and courts

• A minority wanted an independent state, which they call “Ambazonia”

• The Yaounde government’s violent response to protests in the Anglophone regions in late 2016 prompted many more to call for autonomy

• In September 2017, the Ambazonia Defense Council declared war on the Yaounde government

• On October 1, 2017, Anglophone separatists claimed two regions as the self-proclaimed republic of “Ambazonia”

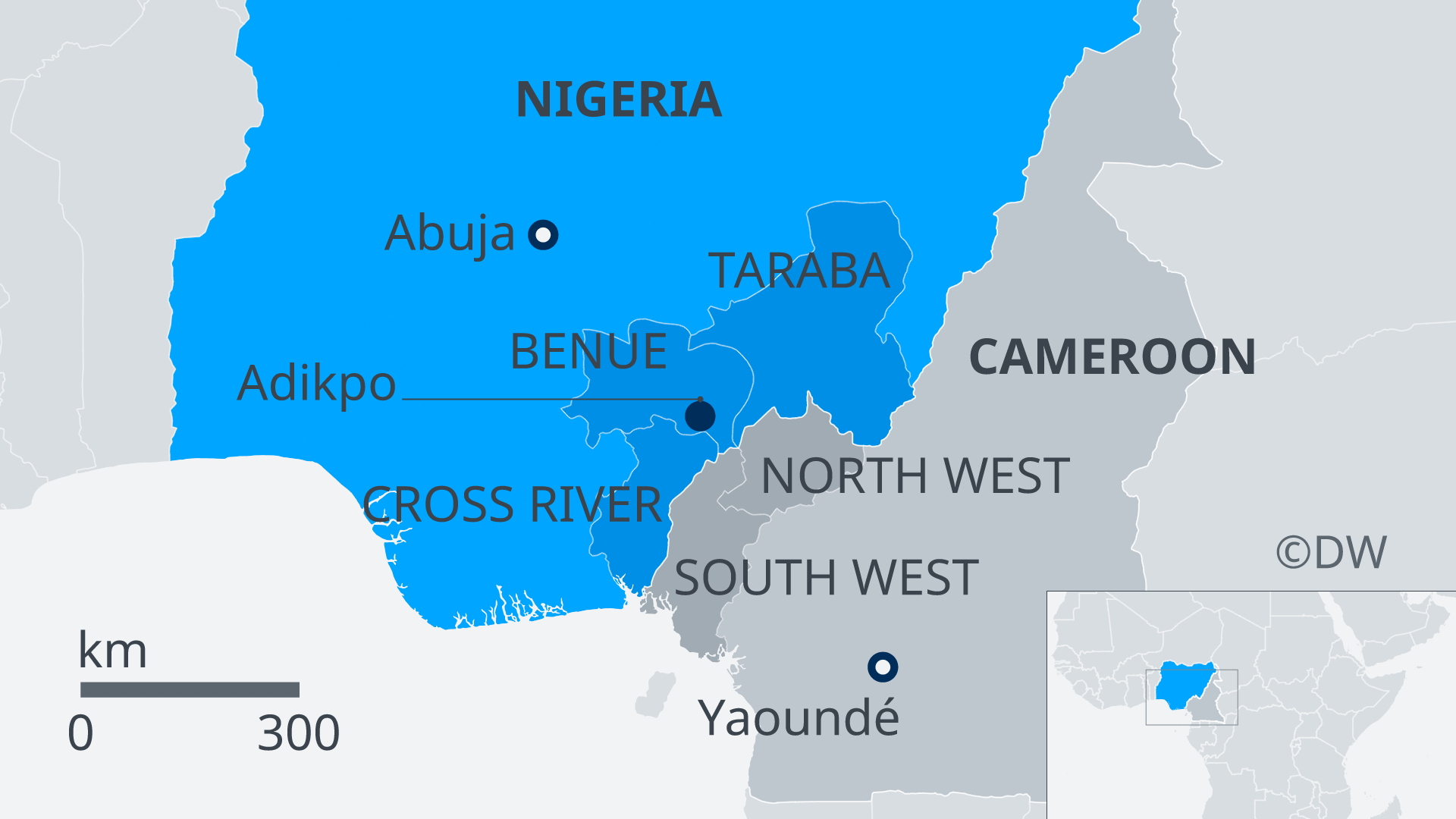

Cameroon is bordered by Nigeria, Chad, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo

Cameroon is bordered by Nigeria, Chad, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo

The West breaks its silence

The international community had for two years turned a blind eye to the Anglophone crisis but that has started to change.

“Cameroon embodies the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, that most people are unaware of,” Jeffrey Smith, the executive director of Vanguard Africa told DW.

Vanguard is a nonprofit organization that partners with African leaders and democracy activists to consolidate democratic gains and advocate for free and fair elections in Africa.

Political observers believe that the arguably worsening crisis in Cameroon is largely due to the Biya regime’s use of violence and brutality as a first resort.

“By immediately resorting to violence, Biya and the country’s governing elite, dumped petrol on a long-smoldering fire, transforming the conflict into the runaway conflagration we see today,” Smith says.

In February, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s personal advisor on Africa, Günter Nooke, held talks with Biya and the governor of the southwestern region.

“He [Nooke] emphasized the responsibility of the government of Cameroon to uphold the significance of human right standards,” a source at German foreign ministry told DW.

In June, the European Union condemned the escalation of the violence and called on Biya to protect civilians and to undertake every effort to resolve the conflict. It also demanded unrestricted access for human rights organizations in the embattled regions and an independent investigation into alleged human rights violations.

Will Biya finally bow to international pressure?

It is hard to predict where Cameroon is headed. One thing is clear, however: Biya is almost sure to win the presidential election in October.

Smith believes that, with a conflict that engulfs a fifth of Cameroon’s population and increasing violations, the trust that was once bestowed on the country’s strongman is waning.

“At home, regionally, and indeed internationally, Paul Biya is losing legitimacy on a daily basis, and rightfully so,” Smith says.

Divisions run deep

• After World War One, the League of Nations divided Germany’s colonial-era regions in Africa between the Allies — most of the land went to France and Britain.

• Most of Cameroon’s went to France. A small portion went to Britain.

• After Cameroon gained independence in 1960, English speakers were given the choice of remaining part of Cameroon or joining its bigger neighbor, Nigeria — also a former British territory.

• They voted to stay with Cameroon but have since felt increasingly marginalized by the French-speaking government in Yaounde hundreds of miles away.

Culled from DW