Cameroon’s church walks line of neutrality amid attacks, possible civil war

When church-brokered peace talks in Cameroon were postponed in August, it testified to the worsening plight of the West African country, where English-speaking separatists have been fighting French-speaking government forces.

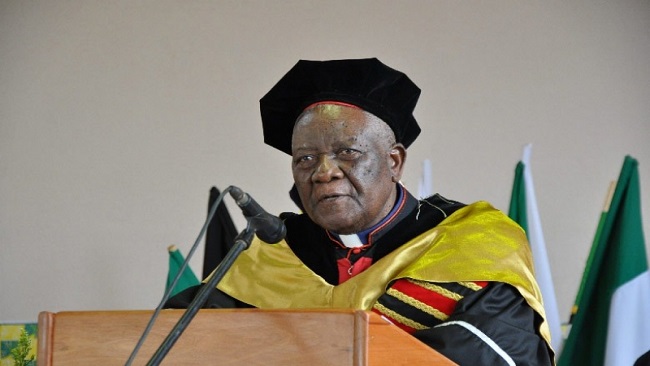

In a statement, the talks’ chief sponsor, Cardinal Christian Tumi of Douala, pledged he and his Muslim and Protestant partners would go on seeking a solution as “politically neutral servants of God.”

But while people of all political leanings had backed the peace initiative, Tumi added, “voices of skepticism, doubt and hostility” had also shown more time was needed.

Even if the talks at Buea go ahead in November, those in charge will face a hard task. Cameroon’s president, Paul Biya, now 85, is seeking re-election this October for a seventh consecutive term on a hardline, anti-separatist ticket.

In a single week of late July, two Catholic priests were killed in what local media said were acts of retaliation against the church’s stand on human rights abuses, while in May shots were fired at the residence of Archbishop Samuel Kleda, the bishops’ conference president.

With similar resistance now facing church mediation attempts in other neighboring countries, it’s unclear whether well-intended gestures like Tumi’s can expect success.

“The Catholic Church is respected enough here for its initiatives to have some impact, especially when they involve other faiths too,” Francis Ajumane, an expert on staff of the Journal du Cameroun daily, explained to NCR. “But not everyone has welcomed this attempt to resolve our crisis, and some members of the ruling party are doing everything to prevent it.”

Army units have been deployed since 2016 in Cameroon’s English-speaking southwest and northwest regions, where separatists declared an independent state, “Ambazonia,” last October on the anniversary of their brief independence from Britain in 1961.

English-speaking officials, whose territory accounts for a fifth of Cameroon’s population of 25 million, had long protested against the imposition of French in local courts, schools and administrative centers, and demanded a return to the federal system which operated until 1972.

Separatist groups have agreed to mediation, but Biya’s government has rejected this, opting instead for a show of force.

This has alarmed the Catholic Church, whose five archdioceses — four French and one mostly English-speaking — claim the spiritual loyalty of a third of Cameroon’s inhabitants, with Protestants and Muslims each making up around a quarter.

In the past, church leaders have opposed any talk of partition. But in a television interview last April, Kleda conceded that mass poverty and unemployment were fueling discontent, and urged measures of decentralization, such as the election of regional presidents to allow people “to think about their future.”

“Peace through armed force is never a true peace,” the 59-year-old archbishop added. “Since we’re all in the same country and all brothers, our message is to stop the violence immediately at all costs, without vengeance, and to accept others who don’t think like us.”

In May, as accusations of human rights abuses and summary executions mounted against government troops, Kleda and his fellow bishops sent out a “Cry of Distress” for Pentecost, quoting Exodus 3:7 — “I have seen the afflictions of my people.”

“The northwest and southwest regions have been passing through difficult times, marked by inhuman, blind, monstrous violence and a radicalization of positions,” the bishops’ conference appeal noted. “Mediation is now more urgent in order in order to come out of this crisis. Please, spare our country, Cameroon, from a useless and senseless civil war!”

Terrorism targets church in entire region

English-speaking separatism isn’t Cameroon’s only security challenge.

Islamist insurgents from Boko Haram, based in neighboring Nigeria, have targeted Catholic clergy and killed hundreds of police, troops and civilians in the country’s extreme north province since allying with Islamic State in 2015.

Human rights groups, including Amnesty International, have warned the English-speaking-versus-French-speaking crisis could soon escalate, and have condemned atrocities by both sides.

So have church organizations such as Vatican-based Caritas Internationalis, which warned this summer that at least 172,000 people had now been forced to flee the country, adding that “whether a person speaks English or French has become a reason to kill.”

The report quoted refugees who’d crossed into Nigeria in panic, describing “running battles” between soldiers and pro-independence fighters, whole villages emptied and civilians shot on the roadside.

The brutality of the separatists, who’ve killed over a hundred members of the security forces, was also deplored by Msgr. Kisito Balla Onana, director of Caritas Cameroon.

With Catholic clergy now increasingly in the firing line, some observers fear a new wave of anti-church violence, as local rulers cling to power in the face of multiple insurgencies and grow increasingly intolerant of the church’s peace efforts.

In the Central African Republic, where spreading violence over the past year has turned once-safe areas into war zones, church leaders have repeatedly appealed for peace and reconciliation, working with Muslim counterparts to rebuild badly strained communal ties.

Source: National Catholic Reporter