Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: Dialogue Remains the Only Viable Solution

A recent spike of violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions points to an emerging insurgency. To prevent more violence as the country enters a delicate election year, the government needs to kick start the political track to head off growing support for the insurgents. It should, with international support, start a dialogue with peaceful Anglophone leaders to discuss the country’s decentralisation and governance.

An Uprising in the Making

In August 2017, Crisis Group sounded the alarm about the risk of an insurrection in Cameroon’s Anglophone region unless a genuine dialogue, complete with strong measures to defuse tensions, was initiated. The crisis, which has been brewing for the past year, regrettably escalated in November when armed attacks were launched against defence forces. Since then, at least sixteen soldiers and police officers have been killed and some twenty injured during thirteen attacks led by separatists. This is four times the number of military victims killed by Boko Haram in the Far North during the same period.

After the defence and security forces suppressed the protests staged from 22 September to 1 October 2017, the separatist faction has taken a harder line and attracted more support. The Manyu division in the Southwest is currently the hotbed of the insurrection, because of its proximity to Nigeria’s Cross River state, home to some of the officials of the “Federal Republic of Ambazonia” (the name given by secessionists to their self-proclaimed state). Most of these attacks have been of low intensity, though some appear to have been more violent. The communications minister reported that 200 assailants participated in the attack on the Mamfe gendarmerie on 8 December, although this number seems to be an exaggeration.

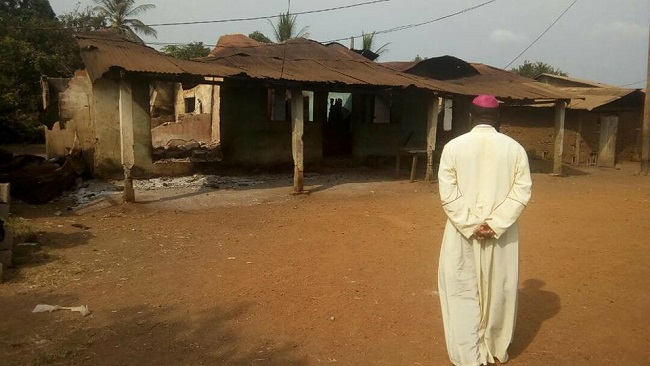

The Anglophone movement is by no means represented simply by its secessionist faction. However, at the heart of the secessionist movement, those calling for armed struggle seem to prevail. Official Cameroonian media and diplomatic sources contacted by Crisis Group have provided information about fighters being recruited and training camps operating in border areas. Those taking up the armed struggle can be divided into two categories. The first consists of around a dozen violent splinter groups or self-defence groups, each with an average of between ten and 30 members, for example the Tigers, Vipers and Ambaland forces. Some of them have carried out arson attacks on markets, shops and schools. The second category is comprised of three rebel militias, numbering more than a hundred fighters in total: the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF), led by Ayaba Cho Lucas and Benedict Nwana Kuah, the Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SOCADEF), commanded by Ebenezer Derek Mbongo Akwanga, and the homonymous group called Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SCDF), under the leadership of Nso Foncha Nkem.

Seven home-made bombs have exploded since the outbreak of the crisis in the Anglophone regions, without claiming any victims; another device was defused in Douala. There are indications that these may have only been tests to give a show of force to the Cameroonian authorities, also in the Francophone region, should the unrest continue to grow.

Ambazonia’s “interim government” has so far rejected the option of an insurrection. But those behind the armed struggle have increased the number of their attacks with the intention of pushing the Cameroonian state into declaring war and thus forcing the hand of the “interim government” with a fait accompli. Under pressure, Ambazonia’s president, Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, is wavering between armed struggle and a strategy of civil disobedience and diplomatic initiatives. His supporters may oblige him to change his mind in 2018 and shift from self-defence to actual insurrection.

The violence since October has created a troubling humanitarian situation. Thousands of people have fled to neighbouring Nigeria, and tens of thousands to other, less-exposed departments or Francophone regions. The situation facing these displaced populations has been exacerbated by a heavy-handed statement made in the beginning of December by the prefect of Manyu, who issued an order to residents of around fifteen villages to leave their homes, at very short notice and with the threat that otherwise they would be considered by the military as being complicit with “terrorists”. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has recorded 7,204 Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria. The Cross River state authorities refer to the presence in their territory of 28,000 Cameroonian refugees, most of whom are not receiving any support.

A Military Response that Risks Antagonising the Population

Faced with a separatist faction lurching toward armed struggle, Cameroon’s president has declared war on secessionists and called them terrorists. International arrest warrants have been issued against the secessionist leaders, yet another wave of military reinforcements has been deployed in the Southwest, and a de facto state of emergency has been imposed in the Manyu division. These steps have unfortunately been accompanied by a refusal to engage in any meaningful dialogue with the militant Anglophone federalists, who have never advocated violence and some of whose members were imprisoned in January 2017 for political reasons.

A year ago, the Cameroonian government held the view that the Anglophone problem did not exist. Ten months ago, radicals within government believed that the crisis would be solved by arresting the federalist movement’s leaders. Instead it has worsened. Today this same radical wing is betting on war, despite the cost in terms of human lives – some sixty civilians, sixteen members of the army and police officers, as well as an indeterminate number of secessionist fighters have already been killed. This bet could prove counterproductive, because the military response will only feed the cycle of violence, make the population more receptive to separatist ideas, and strengthen the position of supporters of the armed struggle at the core of the secessionist movement. Reports were made, including by traditional chiefs, of abuses and serious human rights violations committed by soldiers in the Manyu division.

President Biya will find it hard to stabilise the Anglophone regions through a military response alone, and only at the cost of hard-fought and expensive counter-insurgency war. However, the escalation in the separatist violence is playing into the hands of powerful members of government and military elite, who have been waiting precisely for this to happen to reduce the Anglophone crisis to a simple question of insurrection and therefore justify a purely military response. This radical element within government is convinced that it will be able to swiftly suppress the uprising before the next elections. But it’s a hazardous calculation. Putting down even a small-scale insurrection is difficult when it is supported by a section of the population.

2018: A Year Rife with Danger

The insurrection has only really so far been notable in Manyu division. But if it spreads to other divisions in the Southwest, or even to the Northwest, where separatist feelings are running high, it could spiral out of control. To raise an army, violent separatists simply need more resources. A section of the radicalised population supports them, and manpower is available in Cameroon and from the refugees. This would have repercussions in Nigeria where local backing for Anglophone militants undoubtedly exists. Southeast Nigeria has long been a centre of various irredentist or secessionist disputes, and has several ethnic and political affinities with Cameroon’s Southwest region.

If the uprising gains momentum, there is a real danger of the Francophone regions being affected, especially since many of the separatists threaten to expand violence around the whole country. Such a scenario would cause deep and long-lasting destabilisation in Cameroon, and the party in power would certainly pay the price in the elections scheduled for autumn 2018. The financial and humanitarian cost would be immense. Cameroon’s finance minister has already announced that the predicted 6-per-cent growth in the country’s GDP has ended up dwindling to 3.7 per cent. Although the Anglophone crisis may not have been the sole cause of the economy’s weaker-than-expected performance, it has certainly played its part.

Unless a political dialogue begins soon, Cameroon could find itself in 2018 – an electoral year – facing an increasingly delicate economic and security situation. The gradual formation of an armed insurrection does require military reaction, but it must be proportional and respect human rights. The political solution must remain the top priority. This approach must include a discussion on federalism and decentralisation led by Cameroon’s president himself.

The traditional end-of-year speech gives the Cameroonian president an ideal opportunity to send out a message of calm, take measures to ease tensions and announce the start of a dialogue. International partners still have the chance to give their backing to such an initiative to prevent Cameroon becoming trapped in a long fratricidal conflict. To date they have been content to do the bare minimum, wrongly believing that the crisis poses no direct threat to their economic, political and security interests, whereas destabilisation in Cameroon would necessarily have sub-regional consequences both in Central Africa and in Nigeria, and is also likely to weaken the fight against Boko Haram.

The stakes are high: a destabilised Cameroon would be damaging for everyone. All parties must focus on finding a political solution to the crisis, as well as offer mediation. For the UN and the African Union, now is the time to restore the reputation of their early-warning system and to prevent this crisis from evolving into an insurrection and becoming a dangerous conflagration.

By the International Crisis Group