Ambazonia conflict keeps schools shut

Schoolchildren have become pawns in the fierce conflict between Cameroon’s mainly French-speaking government and separatist fighters demanding independence for the country’s English-speaking heartlands.

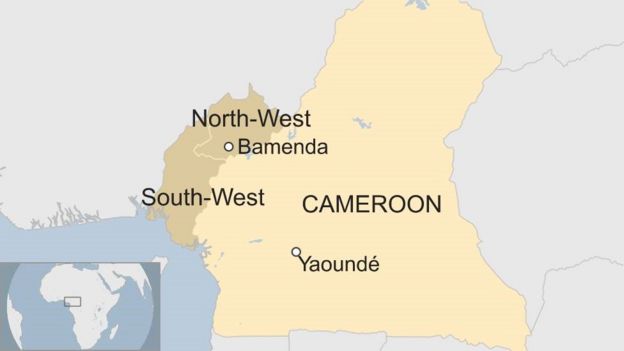

The separatists are enforcing a lockdown across cities, towns and villages in the North-West and South-West regions to ensure schools remain shut for a fourth academic year in a row.

The regions are heavily militarised, with troops battling insurgents who use hit-and-run tactics.

Schools were due to open on 2 September – instead parents and children have been fleeing their homes in their thousands as they fear an escalation of the conflict.

Children abducted

Most schools in the two regions – including in villages – have been empty for three years, with buildings covered by long grass.

In some areas, the government deployed troops to guard classrooms but with the army being the main enemy of the separatists, this increased the risk of attacks by separatist gunmen.

The United Nations Children’s Fund, Unicef, says the ban on education has affected about 600,000 children, with more than 80% of schools shut and at least 74 schools destroyed in the troubled regions.

In one incident, 80 pupils, their principal and a teacher – who defied the lockdown – were kidnapped last year, before being released about a week later.

Separatist fighters denied involvement, but the government blamed them for the abductions.

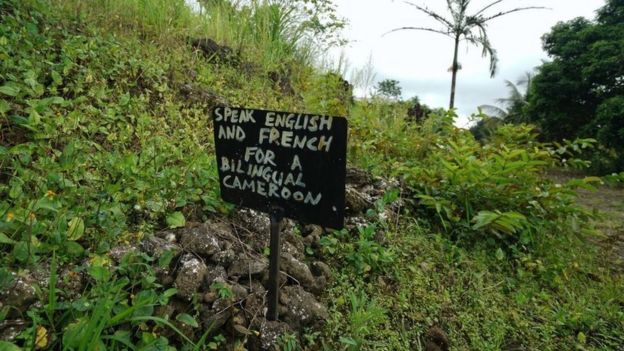

The conflict has its roots in the government’s decision to increase the use of French in schools and courts in the mainly English-speaking regions in 2016.

It triggered mass protests and morphed into a rebellion the following year as some civilians – angry that the government deployed troops to crush the protests – took up arms.

Thousands of people – civilians, separatists and soldiers – have been killed and more than 500,000 displaced.

The economy is also in ruins, with businesses going bankrupt and workers not being paid.

Child soldiers

Worst of all, children have been orphaned and some of them have gone into the bush to join one of the many armed groups that have emerged to fight for what they call the independent state of Ambazonia.

What was once unthinkable has become a reality: Cameroon – like some other African states – now has child soldiers.

They blame government troops for the deaths of their parents and have vowed to take revenge.

The separatists have targeted schools, more than anything else, because they are the softest of targets, and because they want to thwart the government’s efforts to make children – the next generation of English-speaking Cameroonians – fall under greater French influence.

Cameroon – still divided along colonial lines:

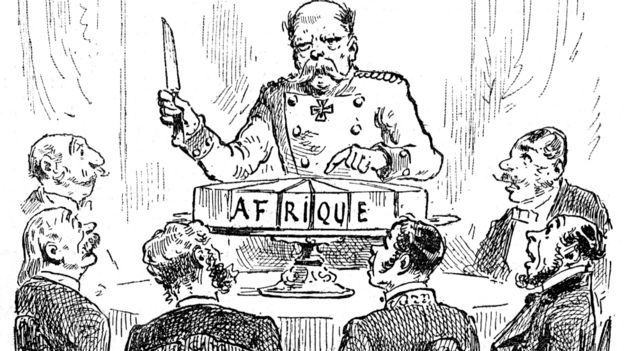

Africa’s borders were “carved up” up by colonial powers

Africa’s borders were “carved up” up by colonial powers- Colonised by Germany in 1884

- British and French troops force Germans to leave in 1916

- Cameroon is split three years later – 80% goes to the French and 20% to the British

- French-run Cameroon becomes independent in 1960

- Following a referendum, the (British) Southern Cameroons join Cameroon, while Northern Cameroons join English-speaking Nigeria

They insist that schools will remain shut until the government agrees to negotiations to create the state of Ambizonia – something that it has so far refused to do, thinking it can defeat those whom it calls “terrorists”.

With no major international effort to end the conflict, both sides have become more belligerent.

Last month, a military court sentenced the self-proclaimed leader of Ambazonia, Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, and nine of his colleagues to life in prison, following their arrest and deportation from neighbouring Nigeria.

‘Head in the sand’

The ruling enraged separatists, who stepped up their efforts to enforce a lockdown by ensuring that residents in the two regions – which have a population of about eight million – to remain at home.

All public transport has been stopped, and shops, offices and markets have been shut.

Security forces are frequently targeted by the armed secessionists

Security forces are frequently targeted by the armed secessionistsIn the past, separatists ordered lockdowns for a day – usually on a Monday. Anyone who defied the order were branded “sell-outs”, and risked being assaulted and even killed. This time, the lockdown will be for two and possibly three weeks.

Bamenda – the biggest English-speaking city with a population of about 400,000 – has been in lockdown since last week, while in other areas the lockdown started this week.

In the days leading up to the lockdown, transport fares more than doubled as thousands of people fled villages, towns and cities for safer areas in mainly French-speaking Cameroon – including the capital, Yaoundé, and the commercial heartland of Douala.

This has worsened the humanitarian crisis, with some people stranded at bus stations in the two cities because they have nowhere to go.

Despite this, some government officials have buried their heads in the sand – the North-West governor, Adolphe Lélé L’Afrique, described those fleeing as holidaymakers returning to their homes before the start of the new academic year.

The majority of people in Cameroon are French-speaking

The majority of people in Cameroon are French-speakingWith such an attitude, many people are in despair, wondering whether there is a future for them – and more importantly their children – in mainly English-speaking Cameroon or whether they should emigrate.

I myself moved to Canada in January, as Bamenda – where I lived – became too dangerous for me to work as a journalist.

Culled from the BBC