What difference does Jesus Christ make? (Part 2)

In the first part of our reflection on the topic of what difference Jesus makes that we published this past Easter, we ended on the position that the Temptations constitute, at their innermost core, a theological debate between Satan and Jesus. The hectic nature of my schedule did not allow for the completion of this reflection until now. I apologize to my readers for this belatedness. Now, let us return to where we break off this past Easter on this topic, namely, the challenge for Jesus to prove his identity as the Son of God. It is likewise important to keep the overarching question in view, that is, Jesus’ identity in the light of the difference that Jesus makes in today’s world. In effect, if Jesus is who he claims to be, if Jesus is authentic – if you are the Son of God – as Satan threw at him, then there must be a difference in the world with the coming of Jesus. Within the context of the Temptations, Jesus does not take the bait put forth by Satan. He refuses to turn stones into bread, or to fall from the lofty heights of the Temple pinnacle. The Cardinal Inquisitor has it right in The Grand Inquisitor when he laments before Jesus: You refused the offer of the Mighty Spirit because you wanted men and women to follow you out of freedom! In other words, succumbing to the Temptations would have been an easier and faster part for Jesus to accomplish his mission. But the fastest and easiest do not always translate into the truly enduring, beautiful and good.

To Ratzinger, the Temptations are not only Christological, that is, pertaining only to the person of Christ. They likewise have an inherent Ecclesiological character, in that the Church down the ages has often faced the challenge to prove itself, to prove its credibility. If you are the Church of Christ, then demonstrate it in a more convincing manner. If you are the Church of Christ, then why is there so much sin and evil in your members? Why couldn’t Christ make you as perfect as he Jesus is? And this temptation to prove one’s identity and authenticity can be very overwhelming even for the priest of today, with all the media hype. In my own life as a Christian and as a priest, I am learning, with every passing day, the wisdom in Jesus’ refusal to take the bait. I am learning that the most meaningful response to the challenge to prove one’s identity and authenticity is to create time for more prayer before God, the all-knowing One. In prayer, the priest and the Christian feels the Lord’s closeness and support, and if my own limited experience in the spiritual life is anything to go by, there is really no substitute for prayer in the life of a priest and a Christian.

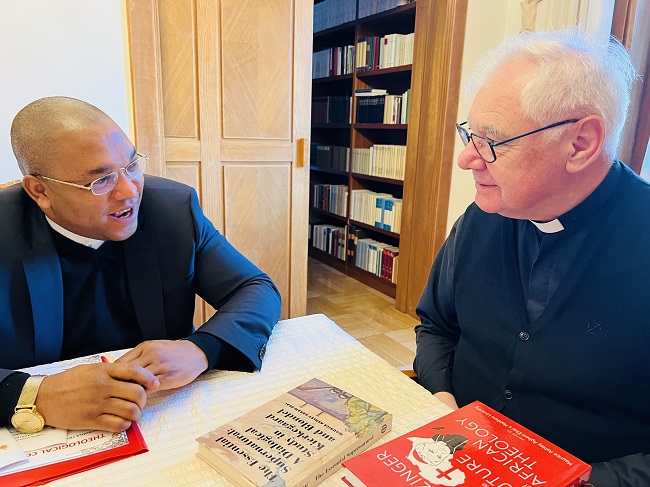

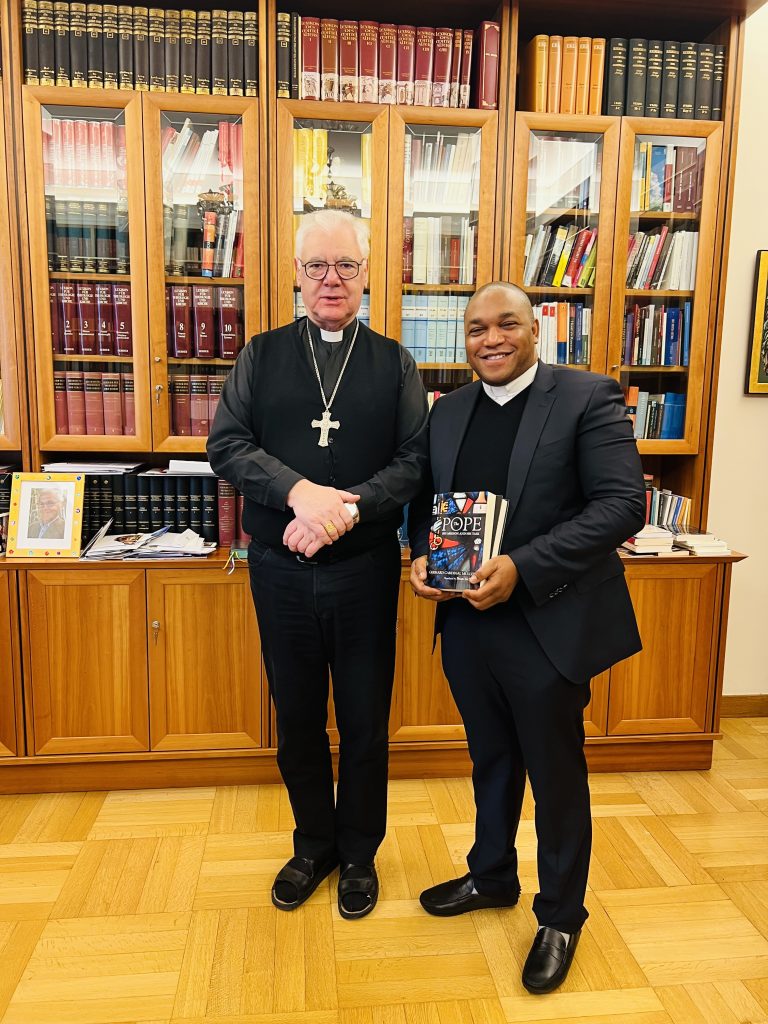

Fr Maurice with Gerhard Cardinal Müller, Prefect Emeritus of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Custodian of Ratzinger’s Theological Legacy (Meeting at Vatican City)

When one enters into an Ignatian contemplation of the Temptations of Jesus, one can discern, overtime, that the issue of the Temptations boils down to the question about the fulfillment of the human heart. What really satisfies the human heart? Wealth (bread), Power (Temple Pinnacle/the cities of the world)? I believe that to understand Jesus’ resistance to the seductive offers of Satan provides the definitive response to the central question of the difference that Jesus makes in our lives today. And a proper understanding of this question possesses a historical pedigree to it, namely, engaging Jesus’ identity and uniqueness from the living faith of Israel, specifically with the figure and mission of Moses.

With Moses at the helm, Israel left Egypt for the promised land. What shaped this journey in large measure was the sense of hope, for a promised land that would meet the aspirations and yearnings of Israel. The particular issues and demands met by manna and other nutritional and safety needs embodied the need for hope in an otherwise hopeless context. The question of difference Jesus makes appears in an antecedent format at this point: What difference does the God of Israel make, to the people of Israel? In a sense, the yearnings of Israel’s heart is captured in the request Moses makes to Yahweh: Show me your face. Some translations render it as show me your glory (Exodus 33:18). God strikes a compromise with Moses that from the angle of a retrospective reading, lays the foundation for the difference that the coming of Christ makes in history. Moses will still have the privilege and joy of encountering, somewhat, the beatific vision while still on this side of human existence, that is, the Back of God, but no more, for the human being cannot see the face of God and live (Exodus 33:20). In the event of Moses, the light of faith (lumen fidei) and the light of glory (lumen gloriae) converge, a rarity, because the light of faith is meant to accompany us in this earthly life, while the light of glory is what enables us to see God in the next life. As I think further about this mysterious text of Exodus 33, this interpretation already much present especially in Eastern Theology occurs to me: the light of faith could correspond to the Back of God, and the light of glory, the Face of God, to the extent that only in followership/discipleship captured in the image of the back, would one eventually arrive at the longing that moves or drives the human heart, captured in the image of the face. From this incident of Moses, there emerged, in the consciousness of Israel’s faith and later on taken up in Christian mysticism, the theology of the Face of God as the fulfilment of the greatest longing of the human heart, as we see in the lives of the saints and Doctors of the Church.

Let’s remain a little bit more with the figure of Moses and the images of the Back and Face of God. In his The Life of Moses, St. Gregory of Nyssa offers a truly moving Christological reading of this mystical event as narrated in the Book of Deuteronomy. Gregory asks:

What is his back which God promised to Moses when he asked to see him face-to-face? (…) But when the Lord who spoke to Moses came to fulfill his own law, he likewise gave a clear explanation to his disciples, laying bare the meaning of what had previously been said in a figure when he said, ‘if anyone wants to be a follower of mine.’ And to the one asking about eternal life he proposed the same thing, for he said, ‘Come, follow me’ (18:22). Now, he who follows sees the back. So, Moses, who eagerly seeks to behold God, is now taught how he can behold him: to follow God where ever he might lead is to behold God. His passing by signifies his guiding the one who follows, for someone who does not know the way cannot complete his journey safely in any other way than by following behind his guide. HE who leads, then, by his guidance shows the way to the one following. He who follows will not turn aside from the right way if he always keeps the back of his leader in view. (Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, HarperCollins Publishers, 2006), 106 & 110.

Some spiritual insights from this engagement between Moses and God:

Firstly, as Aquinas beautifully expresses it – and as many Christians likewise get a glimpse of it particularly during moments of prayer, – only God can satisfy the human heart – Nil Nisi Te Domine. Augustine had said it best centuries before Aquinas: You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until it rest in Thee.

Secondly, notwithstanding all the material blessings that come our way in this life, there remains that longing that nothing corporeal is capable of filling. There is a void, what the French philosopher Maurice Blondel trenchantly characterizes as the wedge between the willed will and the willing will, in his philosophy of action.

Thirdly, because this quest for God is in the DNA of the human being, we are somewhat impatient for the beatific vision, for what Aquinas calls the light of glory. Even in this life, which is guided by the light of faith, we want to have the fullness that the light of glory brings with it. And this is quite understandable, for who wants to live with half measures?

But even more, we cannot deny that our brokenness and sinfulness, what Blaise Pascal calls our wretchedness, is likewise a motivation for our desire for the fullness that comes with the light of glory, the Face of God. I love Dante’s DivineComedy precisely because sin is not presented in a despairing form, but as a starting point for the journey to the Face of God, as the soul moves from the Inferno through the Purgatorio and finally, Paradiso. Too often, Christians get chained in the melancholy of their sinful past and present, forgetting to realize that our sins, my own sins as Maurice, is really the raw material that God uses to place me on the journey towards Him.

And this is the context in which Jesus Christ enters the scene, making all the difference, as particularly captured in the dual dynamisms of Deuteronomy 18 and Matthew 17. (To be continued…)

By Maurice Agbaw-Ebai