Ambazonia would be a potentially rich nation, battle for independence far from over

State of confusion

Ambazonia would be the first new country in a decade, and a potentially rich one. But, as Tortoise Media reports, the battle for independence from Cameroon is far from over

Last June, the InterContinental hotel in Geneva cleared its 16th floor for an exceptionally loyal and lucrative guest. At $40,000 a night for his family and entourage, President Paul Biya of Cameroon has been favouring the InterContinental with his business for longer than many of its staff can remember. He stays there when health concerns bring him to Switzerland, and frequently for summer holidays. In 2019, his 37th year in power, he might have had a third agenda item too: a Swiss offer to mediate a conflict that threatens to split Cameroon in two and turn part of it into the newest country in the world.

Biya declined the offer but his break was still rudely interrupted. Cameroonian emigrés infuriated by his extravagance (average earnings in Cameroon are less than $10,000 a year) staged daily protests outside the hotel on Chemin du Petit Saconnex. Swiss police tried everything to move them on, including tear gas and water cannon. The protesters wouldn’t budge and so Biya was asked to leave instead.

The point of the protest was “to ask Mr Biya to go home and receive medical care in Cameroon”, Marcela Nkwi, one of its organisers, told me. “If he wants to sleep in a luxury hotel, he should build them in Cameroon and sleep there. Geneva was a battlefield and the Swiss don’t like disorder as it inspires others.”

Later, I visited the place that is defying Biya and the weight of its own history to aspire to nationhood. It consists of Cameroon’s two westernmost regions – the only two where English rather than French is an official language. It’s half the size of Portugal and could be rich and bustling. Instead, it has become a battleground where violence can suddenly give way to emptiness and silence.

Walking through the town of Tiko felt like being in an epic Western, with the wrong plot. There were no sandstorms, no cowboys riding horses, only empty wooden market stalls on the roadside. In Mutengene too, to the west, human activity had come to a halt. To the north, in Muyuka, metal sheeting sealed the doors of shops, restaurants and supermarkets. Along the slopes of Mount Cameroon, there was an endless string of military checkpoints set up to control an invisible population outlawed as terrorists by its own government.

The wind was the only soundtrack, interrupted by gunfire and stray bullets, because these two regions are sliding towards war. They should be lucky places. They form a rough oblong of territory blessed with extraordinary natural wealth. Their volcanic soils are preternaturally fertile. Their dark brown beaches are a well-kept secret. Their coastal waters give access to largely untapped oil and gas, and their people are confident enough to have set their heart on self-determination. If their dreams come true they will create the first new country in nearly a decade, after South Sudan. It could become one of the richest in Africa, and it would rejoice in the name Ambazonia. The word derives from Ambas Bay, an historic indent in the West African coast at the mouth of the Wouri River, where in 1858 an English missionary founded a settlement for freed slaves.

Ambazonia is a place, but also a cause. Over the past three years it has served as a rallying cry for nearly 5 million English-speaking Cameroonians whose parents and grandparents were forced into a French-speaking country 60 years ago and kept there, they say, as second-class citizens.

Parts of this territory have become no-go zones for Biya’s army. Others have felt his wrath: his soldiers have torched nearly 300 towns and villages leaving at least half a million people in internal exile. On satellite pictures, where there used to be neatly demarcated streets and compounds, there are now grey smudges.

Ambazonia’s self-proclaimed leaders sit in prison in the French-speaking capital, Yaounde, but most of their homeland is controlled from day to day by bands of armed volunteers who have filled Ambazonia’s power vacuum with incipient anarchy.

These are the Amba Boys, some as young as 15. Between flashes of violence they preserve a sort of calm, as if before the storm. Their cause is financed by a Cameroonian diaspora spread from Oslo to Birmingham and Houston to suburban Washington. Their time, they are convinced, will come.

Within the territory they claim, Ambazonians have ceased recognising central authority. Their default posture is non-violent resistance: businesses and individuals have stopped paying taxes and started using what they call “ghost town” tactics against the regime, rather as Marshal Kutuzov used the evacuation of Moscow against Napoleon. To vanish, they have learned, is to prevail.

They used similar tactics to sabotage Cameroon’s latest elections, on 9 February: both Anglophone regions boycotted the poll, as did the official national opposition, leaving Biya’s ruling People’s Democratic Movement with an overwhelming but meaningless majority.

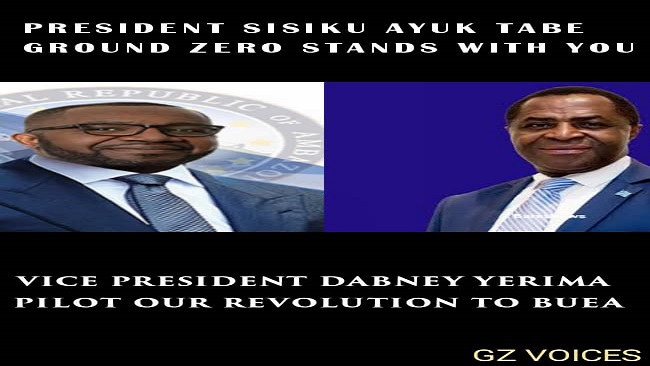

For now, Biya remains nominally in charge and Ambazonia’s two halves are still officially called the Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon. But on 1 October last year the people of Bamenda in the grasslands of Northwest region came out to celebrate their independence and chant the name of Sisiku Tabe, an engineering graduate from the University of Sheffield.

Exactly two years earlier, Tabe had declared Ambazonian independence. At the time he held a teaching position at the American University of Nigeria in the Nigerian capital of Abuja, and it was there, three months later, that he was hosting a cabinet meeting of the Ambazonian government in exile when Nigerian police broke into the meeting room in the Nera Hotel and arrested them all. They were extradited to Cameroon and consigned to Kondengui maximum security prison in Yaounde, where they are still being held, and where their sense of destiny is palpable.

“We have learned from the Tamils, the Sahrawis [of Western Sahara] and the people of East Timor, South Sudan and Kosovo,” said Fidelis Ndeh-Che, one of the prisoners. “Nothing will change the inevitable march of history.”

Since the start of the war the Cameroonian army has been stationed along Ambazonia’s western border to intercept weapons from Nigeria’s black market. From the east, the government deploys militias that can be disowned when diplomatic appearances require, and from Douala, Cameroon’s commercial hub, prisoners have been released to wreak havoc in the Northwest and Southwest regions. “Thieves and bandits have deserted the economic capital and relocated to Ambazonia, where war brings more opportunities,” Halima Alim, a Douala based police officer, told me.

There is no real centralised command in the Ambazonian heartland that the Amba Boys call Ground Zero, only a loose co-operation between each community patrol group dictated by the rhythm of military clashes. Most Amba Boys are aged between 16 and 25, forced out of school and armed only with “den guns” from their parents – weapons traditionally used during cultural celebrations such as weddings. They now make do with captured weapons from government soldiers, and with spirituality.

“When Amba Boys call you have no choice but to respond,” Che Paul Bih, a taxi driver in Ekona, told me. “They called me to come sit with them and eat, to find out if I was on their side. We ate dog meat [a taboo food] to mark our alliance and they taught me the coded language.” That language is partly visual, partly verbal.

Some Amba Boys wear distinctive red beads with supposedly bulletproof properties, reminiscent of the Edochie cult in Nigeria. For added protection, some also cut themselves to insert charms under their skin, and all use incantation – a form of prayer.

Real Amba Boys, Bih added, claim a higher moral ground than the fake ones, who steal phones and money, or the government soldiers, who kill and rape. They don’t harass; they “advise”, he said. “But if they see you as a black leg, as someone who is against them, they will take you to their camp to explain yourself. If you don’t talk they will keep you in the bush and tell the government ‘we have taken one of your people’.”

In their diversity, the people of the Cameroons have an attitude that could be misread as passivity. Like Ugandans, they know they are spoiled by extravagant natural abundance and don’t make a big fuss of it. They also wear a mane of stubbornness, borrowed from their national football team – known as the Indomitable Lions.

But this only partially explains why the Cameroonian army in all its might, with modern artillery and armoured vehicles, has failed to crush the Ambazonian independence movement. Its leaders are convinced they are righting wrongs inflicted on a people who were forced into a cohabitation with a partner whose language they don’t speak. In the late 19th Century their homeland was colonised by the newly unified Germany and named Kamrun. In 1919, as part of the Treaty of Versailles, it was divided between France and Britain. In 1961 a UN resolution declared that the Ambazonians’ forebears had “decided to achieve independence by joining the [Frenchspeaking] independent Republic of Cameroun”. But the details of their relationship with the republic were left to “urgent discussions” – which never happened. For four of the six decades since then their fate has been bound up with that of President Biya, one of Africa’s longest-serving dictators and a Francophone to his core.

Like the Kikuyus of Kenya and the Igbos of Nigeria, the Ambazonians’ cause is one of economic selfempowerment. But it is also, crucially, a reaction against Biya’s policy of forced Francophonisation; of governing in French in a place that doesn’t speak it. It is not hard to find French-speaking Cameroonians who see why this can’t work.

“How is it possible to judge an Anglophone in French when he cannot understand what he is told?” asked Emmanuela Afewo in Limbe, a surf town on the Atlantic coast. “How can he be told ‘tu signes’ [sign here] and be sent to jail? How can Francophone teachers be sent to teach Anglophones when they don’t speak the language of their students?”

Last October, startled by the depth of popular support for Tabe and his imprisoned cabinet, Biya convened a “national dialogue” intended to steal their thunder. It achieved the opposite. The secessionists were not represented and Biya wrapped up proceedings stating that “the future of our fellow citizens in Northwest and Southwest is in our republic”.

The dialogue served only to raise the stakes in a conflict whose participants fear will end if not in the creation of a new country, then in genocide. Charity workers say 20,000 people may have been killed since the violence began, many of them burned along with their villages and buried in mass graves.

This scorched earth strategy might have achieved its aim by now, but for the Cameroonian diaspora. Thousands of Cameroonians, Francophone and Anglophone, have left the country during Biya’s decades of misrule. Many are now wealthy, and some took part in the protests that embarrassed the Swiss into sending Biya home from Geneva last year. Others have been peacefully protesting in front of the Cameroonian embassies around the world.

In London, they use eggs. “Seven of us have shut the embassy down without breaking the law,” Kingsley Sheteh Newuh, a Cameroonian political scientist based in Birmingham, said. “We believe in pressure rather than violence. We would buy a thousand eggs to throw at the embassy building in protest. We chose eggs for each life that is killed in Cameroon.”

Different pockets of the diaspora support – and fund – different groups of Amba Boys. The Ambazonia Defence Forces is backed from Norway by Lucas Ayaba Cho, a former youth organiser. The Southern Cameroons Defence Forces is led from Maryland by Ebenezer Akwanga, an ex-trade unionist. Another group is part-funded from Houston by Chris Anu, a pastor facing allegations of embezzlement whose brother leads yet another – the Red Dragons and Tigers – in the hills of Lebialem.

Cho and Akwanga are seen as hardliners embittered by long periods of imprisonment in the 1990s. They have distanced themselves from Tabe since his emergence in 2017, believing he enjoys the legitimacy that they earned. With Tabe’s imprisonment, infighting and intrigue in the diaspora has intensified to the point of farce.

In 2018 Samuel Ikome Sako, a preacher living in Baltimore and moonlighting as acting president of Ambazonia, launched a multimillion-dollar online fundraiser that he called “My Trip to Buea”. It was billed as a sort of liberation pilgrimage to Buea, a bucolic town on the eastern slopes of Mount Cameroon that Ambazonians regard as their Jerusalem.

With tickets going for up to $8,000, Sako promised to deliver a state in three months or else resign. He later withdrew the pledge in a live Facebook interview, claiming he was no longer able to deliver the new country because his demand for $2 million had not been met.

It was, says Martha Tataw, a Cameroonian accountant based in Paris, “the most elaborate scam” – but more broadly the diaspora has lobbied effectively against the Biya regime. The US has suspended military aid and the UN Secretary General, António Guterres, has called for a new dialogue with all “stakeholders” present.

West of the Bonabéri Bridge over the Wouri River, the natural boundary between Cameroon’s two linguistic communities, Ambazonia unfolds as a giant agro-industrial complex that starts 20 kilometres west of Douala. Here, 42,000 hectares of bananas, rubber and palm oil are grown, processed and marketed for foreign export by the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC), the country’s second-largest employer.

Twelve of Cameroon’s 14 functioning oil and gas pipelines come ashore on Ambazonia’s coastline. All told, the region accounts for 60 per cent of the country’s $35 billion economy. Independence movements can be awkward when so much is at stake. Ambazonians believe they were tricked into choosing between Nigerian and Cameroonian independence in 1961. Their uprising is a blow to foreign companies that have invested heavily in the country’s infrastructure. It has upset relations between the CDC and Del Monte, for example, which buys 98,000 tonnes of bananas every year from Ambazonian plantations. And it complicates life for foreign stakeholders in a new $1.5 billion Etinde gas field off the coast – among them the Scottish company Bowleven and Russia’s Lukoil.

Beneath the surface, a jumble of players is fighting for control of the Gulf of Guinea, a choke point for the transport of oil and goods to and from central and southern Africa, and a node of instability between the kleptocracies of Equatorial Guinea and the Central African Republic (CAR). France’s President Macron is anxious to bind Cameroon into a single currency for 15 West African countries that would deepen French influence over them all. Bowleven’s stake in the Etinde field was announced by Liam Fox, the then UK international trade secretary, as part of Britain’s push to expand into new territories post-Brexit. And Russia, which has upgraded Africa to a foreign policy priority, is using mercenaries from the Wagner Group to establish a post-colonial outpost in the CAR.

But Ambazonians themselves are fighting above all for control of Buea. Built at the heart of the plantations, Buea was Cameroon’s first capital, and even now it exudes a distinct colonial charm. There is one road in and out. It leads ultimately to Yaounde, 200 miles to the east, where on 1 October last year, I saw Sisiku Tabe sing Next Year in Buea, the anthem of a country-in-waiting, behind bars in Kondengui prison.

Tabe likes singing. He and the nine others arrested in Abuja are now serving life sentences handed down by a military tribunal, and they sang in court as the verdict was read out. In the prison I sat in the sun in an exercise yard with the men who have become known as the Nera Ten. These are all fathers and grandfathers who, at 50 and older, have become Cameroon’s most dangerous criminals. What I saw were men who – like their people on Ground Zero and abroad – knew they were free.

“We need ourselves, we have ourselves and we will do it ourselves,” Tabe said. “We have all studied in Western universities and we have nothing to envy Westerners. They know that and they are afraid that we’ll set an example to other Africans. It is either total independence of Ambazonia or resistance for ever.”

As I stood up to leave, all ten of them gathered around me in a circle and held hands. Nfor Ngala Nfor, the 67-year-old leader of the Southern Cameroons National Council, offered a short prayer. It was “for our enemies in the Cameroonian government to free us”, he said, “so that we can go work the land and leave it for our children”.

Cameroon may be doomed to repeat a familiar cycle of insurgency and vengeance – or, just possibly, it may bequeath to the world a small, perfectly formed new country with every opportunity to thrive. Much will depend on the man with a weakness for Swiss five-star hotels, but the current of Ambazonian independence runs strong. From what I saw, it has the power to sweep away the past.

The story was written and published by Tortoise