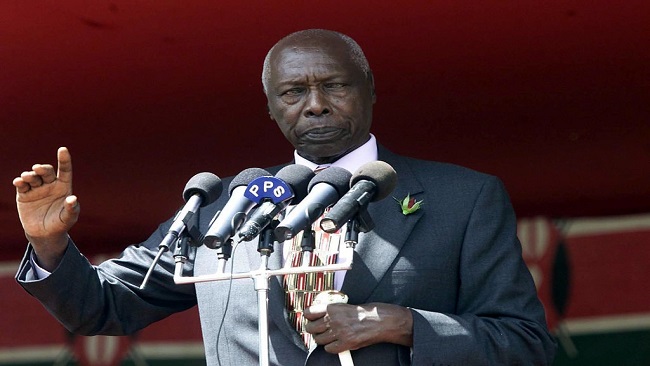

Daniel arap Moi, Who Ruled Kenya for Decades, Dies at 95

Daniel arap Moi, the autocratic president of Kenya from 1978 to 2002, who ruled his East African nation in a postcolonial era of political repression, economic stagnation and notorious corruption, but in the end gave up power peacefully, died on Tuesday at Nairobi Hospital in the capital. He was 95.

President Uhuru Kenyatta, who announced the death, declared a period of national mourning and said Mr. Moi would receive a state funeral. His statement did not specify a cause of death.

Fifteen years after Kenya won independence from Britain in 1963, Mr. Moi became president on the death of Jomo Kenyatta, the country’s founding father. Mr. Moi, a former schoolteacher and national legislator, had been a handpicked vice president and served in Mr. Kenyatta’s long shadow.

Unlike the imperial Mr. Kenyatta, who governed behind closed doors, Mr. Moi traveled the country, courting its ethnic and tribal groups and gaining wide popularity. He introduced free milk for children, and pledged to do away with endemic graft and elevate Kenya’s struggling tourism-and-agriculture economy. He won Western support with anticommunist policies during the Cold War.

But after suppressing opposition and consolidating power in a single-party state, he began a 24-year dictatorial reign. Mr. Moi — with his nimbus of silver hair, buttonhole rose and ivory walking stick — dominated life in Kenya. He put his face on bank notes, ordered his portrait hung in offices and shops, enriched his family and tribal cronies and, as investigations showed, stashed billions in overseas banks. For much of his tenure, it was illegal even to speak ill of him.

Kenya remained an island of political stability in East Africa, but a democracy in name only, and a land of stark contrasts: dire poverty and fabulous wealth, natural beauty and decaying infrastructures, luxury safaris for foreigners and vast slums for Kenyans, who faced unemployment, crime, epidemic AIDS and one of the world’s highest infant mortality rates.

Mr. Moi won five successive elections. In 1979, 1983 and 1988, he and his Kenya African National Union ran unopposed. Although some 1,000 people died in clashes over constitutional reforms, multiparty elections were held in 1992 and 1997. But the opposition was divided and disorganized, the balloting was marred by widespread violence, and Mr. Moi was re-elected both times.

As the head of state and government, he exercised absolute power. The post-independence constitution vested legislative authority in a National Assembly and provided for an independent judiciary. But Mr. Moi had the right to dismiss judges and other officials, and he and his party controlled legislation and the courts, overriding decisions and suppressing democratic reforms.

Opposition led by intellectuals arose. But Mr. Moi, who also controlled the news media and the police and military services, and whose pronouncements had the force of law, closed the universities and suppressed his opponents with detentions, torture and killings, according to United Nations investigators and human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Africa Watch.

Official corruption, abuse of power and a deteriorating economy exploded in 1982 in an attempted coup by low-ranking air force officers. But army loyalists crushed the uprising and Mr. Moi ordered the arrest of the entire 2,100-member air force. Hundreds were imprisoned or executed, and the service’s ranks were replaced. He also ordered all civil servants to join the ruling political party, of which he was president.

Despite Western military and economic aid and income from tourists drawn to Kenya’s game preserves, the economy lagged for most of Mr. Moi’s tenure, mired in corruption that affected all manner of transactions, from cab rides and the delivery of goods and services to bribery and kickbacks in public and private dealings.

Investigations after Mr. Moi stepped down found that his government had lined the pockets of his family and its allies with as much as $4 billion. The biggest fraud in Kenya’s history, the Goldenberg affair, in which the central bank paid incentives to a company for exporting gold, diamonds and jewelry that did not exist, cost taxpayers billions and sent Kenya’s economy into a tailspin in the early 1990s.

When he was still vice president, Mr. Moi met President Jimmy Carter at the White House in 1978, and after becoming president he met President Ronald Reagan there in 1981 and 1987 (when he also met Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in London). But after the Cold War, the West no longer regarded Kenya as a strategic outpost, and Mr. Moi was increasingly seen as a despot.

Constitutionally barred from running in the 2002 elections, he agreed to give up power in a smooth transfer that was then still rare in Africa. He supported a son of Jomo Kenyatta, but Mwai Kibaki, who had lost to Mr. Moi in 1992 and 1997, and who was nearly killed in a traffic accident during the campaign, won the presidency by a 2-to-1 margin. Mr. Moi later supported his old opponent’s re-election.

As Mr. Moi retired, his successors found even more corruption and human rights abuses than had been suspected. A 2003 inquiry exposed torture cells at Nyayo House in Nairobi, a government building where dungeons yielded evidence supporting the accounts of victims.

Mr. Moi was never prosecuted, though corruption inquiries implicated him and his family. Kenya in 2003 found $1 billion in stolen funds in overseas accounts. Others in his administration were pursued, but Mr. Moi was treated as an elder statesman.

“We recognize that former President Daniel arap Moi is an important democratic commodity, not only for us, but for Africa,” Mr. Kibaki’s anticorruption chief, John Githongo, told The New York Times in 2003. “He is treated special. He is different. He’s just not any other guy.”

He was born Toroitich arap (son of) Moi on Sept. 2, 1924, in Kuriengwo, a Rift Valley village in Western Kenya. His father, a herdsman, died when the boy was 4. In a nation dominated by the Kikuyu tribe and its chief rival, the Luo, the Moi family belonged to the Kalenjin minority, one of several dozen tribal groups.

At the African Mission School at Kabartonjo, Mr. Moi became a Christian and adopted the name Daniel. He graduated from Kapsabet Teacher Training College; from 1945 to 1947, he taught classes, and he was later the headmaster of a government school.

He married Helena Bommet in 1950. They had five sons and two daughters, and adopted a daughter. The couple separated in 1974. His wife, known as Lena, died in 2004.

He did not join the Kikuyu-led Mau Mau rebellion against British rule in the 1950s, but sympathized with the movement and once harbored five fugitives at his home. He entered politics in 1955, appointed by the British to the colonial Legislative Council. Two years later, when black Kenyans were allowed to vote, he was elected to the council.

In 1960, he joined a London conference that drew up a Kenyan constitution authorizing African political parties. He was elected assistant treasurer of the new Kenya African National Union (KANU), the political instrument of independence, which later merged with the rival Kenya African Democratic Union he helped found and became the sole political party.

In the new government, Mr. Kenyatta appointed Mr. Moi minister of home affairs in 1964 and vice president in 1967. He handled day-to-day government affairs and represented Kenya at the Organization of African Unity, the first continent-wide association of independent states, and other international forums.

Mr. Moi lacked the Kenyatta magnetism and was little known abroad until he became president, but was moderately popular at home. Many Kenyans regarded Mr. Moi as puritanical because he did not drink alcohol or smoke, denounced hippies and miniskirts, led Kenya’s Boy Scouts and recited aphorisms against materialism and acquisitiveness.

After leaving the presidency, he lived quietly, largely shunned by Kenya’s political establishment, but drew crowds in public. In 2005, he opposed a new constitution, which was defeated in a referendum. In 2007, he was named a special envoy to Sudan.

Source: New York Times