Cameroon’s diaspora: learning to live with the enemy within

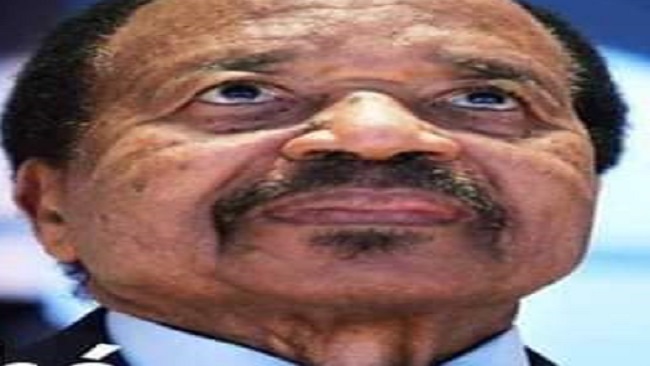

While exchanges of friendship continue between Paul Biya and some of his compatriots living abroad, Cameroon’s President clearly has not digested the violent protests by activists during his recent visits to Europe.

He referred to the protests in his traditional 31 December speech, criticising the “excessive behaviour of some of [his] compatriots in the diaspora” — and questioning “whether they are or are no longer Cameroonians”.

“I think they should, out of patriotism, refrain from negative comments about their country of origin,” Biya said. “One should always respect one’s homeland, its institutions and those who embody them.”

The head of state’s attempt to sound reasonable is unlikely to smooth relations with his critics.

Rights and duties

By distinguishing between those who are Cameroonian and those who are no longer Cameroonian, he is, in effect, creating a category of second-class citizens. While Cameroon does not recognise dual nationality, those who have acquired a new one and have therefore in principle lost or renounced their original one, with all the rights attached to it, are nonetheless subject, according to the President, to the obligation to be patriotic. Otherwise formulated, they have no rights, only duties.

Economic migrants

How can one demand a love of country from people whose exclusion was planned by national laws? Men and women who are both ineligible and banned from voting but also subject to visa requirements to go on holiday or visit their families in their home countries?

One can understand, if not share, the acrimony Biya feels towards, in particular, those who barricade the headquarters of the French and Swiss hotels where he loves to stay. But the head of state must know that they too have grounds for complaint.

Since the 1990s, the profile of the “diaspos” has changed. They are no longer mostly globally educated students from families of executives. They are now mostly economic migrants, young people from less-privileged backgrounds who have decided to take the road to exile as the situation in Cameroon deteriorates.

At the end of the 2000s, the trend became even more pronounced when the middle classes joined the flow of travellers. They emigrated far away but kept family ties and, sometimes, real estate in their home country.

It is therefore fanciful to believe, even for a second, that these people could resign themselves to being dispossessed of any possibility of improving governance in Cameroon. They will never be satisfied with being perceived by the authorities as nothing more than providers of foreign currency – in 2018, according to the World Bank, Cameroonian migrants transferred about 201bn CFA francs ($340m) to their country of origin.

Retrograde scheme

They will never accept a shadowy nationalism that questions the loyalty of the diaspora and treats it as the “eleventh region” of the country or the “fifth column”, as the case may be. Of course, there would be no war in the North-West and South-West regions without the funding of some of the English-speaking emigrants. However, it would be wiser to address the root causes of this devastating conflict rather than its symptoms alone.

Cameroon has a choice. It can establish dual nationality, as the vast majority of countries on the continent have done, which has a more respectful and rewarding approach to the diaspora. This measure would have the advantage of removing obstacles to mobility and would make it possible to reap the economic and emotional benefits of openness. It could also maintain this retrograde and counterproductive arrangement, which is concerned with excluding rather than bringing together. But it will then have to resolve to live with this enemy from within.

Culled from The Africa Report