Biya Must Make Concessions to End the Anglophone Crisis

Cameroon has been embroiled in a deepening secession crisis for more than three years as fighters in its English-speaking regions attempt to break away from the country’s French-speaking majority and establish their own state: Ambazonia.

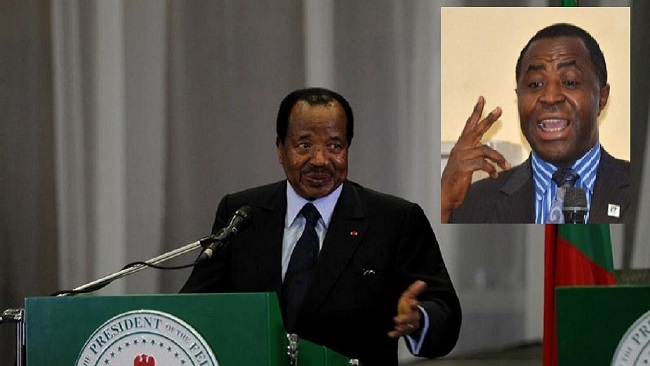

On Sept. 10, Paul Biya, the country’s reclusive president, announced his intention to start a national dialogue with the aim of resolving the crisis. It was the first time Biya publicly acknowledged the disturbances in the country’s Anglophone regions, whose inhabitants make up about one-fifth of the population.

Many Anglophones see Biya’s government and its heavy-handed military and police as responsible for shaping the crisis into its current form: Over a third of people living in the country’s Northwest and Southwest regions, where most Anglophones live, now require humanitarian assistance. The conflict has killed 2,000 people and left more than 500,000 internally displaced. In the areas most affected, it has radically disrupted everyday life, with 40 percent of health care centers and 80 percent of schools still shuttered. On occasion, classrooms have been repurposed as bases for armed separatists, and children fear gunfire on their way to school.

Cameroon’s ability to piece itself back together depends on the government’s willingness to sit down with the right negotiators on both sides at the table, take into account the deep historical roots of Anglophone grievances, and engage seriously with Anglophone proposals on ending the crisis. So far, the Cameroonian state has been focused on reestablishing the preconflict status quo, with minimal concessions on issues central to the unrest: language policy, education and legal reform, and representation of Anglophones in government. Yet what most Anglophone Cameroonians want is substantial regional autonomy and a credible commitment to address both historical injustices and perceived structural discrimination in everyday life. Without these elements, the potential upside of a national dialogue—securing a cease-fire, ending widespread human rights abuses, and preventing a descent into civil war—will remain unrealized.

Public opinion among Anglophone Cameroonians will shape how the armed separatist movement evolves.

One of us, Claire Hazbun, conducted research on the ground in November and December of 2018 exploring the preferences and experiences of a group of more than 80 Anglophone Cameroonians living in the capital, Yaoundé—many of them new arrivals there displaced by the conflict. This survey is not statistically representative of the views of Anglophones, but it provides important insights into how they tend to see the crisis and what solutions they might accept. Overall, the evidence points to an increasing loss of faith in both the Cameroonian state and moderate Anglophone leaders, who have been willing to work with Biya. If he genuinely wants to end hostilities through nonviolent means, as he claims, he is facing an uphill battle.

Separatism has found supporters in some Anglophone circles for decades, albeit on the fringes. But now, at least in this key demographic, it has become an increasingly popular idea. Four in 10 interview subjects said that their preferred outcome would be outright secession.

Unfortunately, Biya’s latest speech betrayed a continuing inability—or unwillingness—to acknowledge the enormity of the problem. In his view, the crisis is about disgruntled teachers and lawyers who object to Francophone language policies. However, the problem runs far deeper.

More than two-thirds of survey respondents in Yaoundé believed that grievances driven by historical marginalization were the primary cause motivating Cameroon’s secessionist movement. While a number of Anglophones pointed to proximate injustices such as their inability to return home, or the killing of a family member, many readily pointed to deeper historical problems. They blamed the government for biased allocation of development resources in favor of Francophones and the erosion of Anglophone regional autonomy since independence. A common thread is the sense of structural discrimination at the hands of the Francophone majority in nearly all sectors of life.

Before independence, English-speaking and French-speaking Cameroon were administered as separate entities under the British and the French. After World War I, the former German Kamerun Protectorate was split into separate mandates administered by the two powers. The Francophone region gained independence in 1960, and the Anglophone region in 1961. The two parts were then reunited in 1961 as the Federal Republic of Cameroon, after what had been British-administered Cameroon elected to join French Cameroon, rather than neighboring Nigeria.

The federal system allowed for some local autonomy—with a president, prime minister, and control over certain regional aspects, such as customary courts and primary education. Importantly, many of these powers were conferred by convention and not enshrined in the constitution. This reality made it possible for the postcolonial government of President Ahmadou Ahidjo to systematically dismantle the federal character of Cameroon, culminating in the declaration of a unitary state in 1972.

In 1996, Cameroon adopted a new constitution, which provided for a decentralized system of government. However, the Biya administration has only selectively implemented this feature of the constitution, opting to centralize power instead. Biya’s concentration of presidential authority amid rising economic hardship, combined with experiences of structural discrimination and both perceived and real disparities between Francophone and Anglophone regions, have all exacerbated the grievances expressed by Anglophone Cameroonians.

Culled from Foreign Policy