The Brexit divorce deal: What’s next?

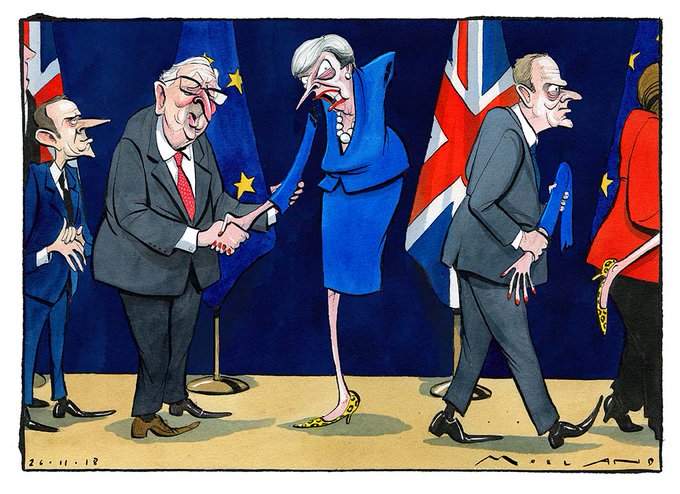

EU leaders finally rubberstamped a 585-page withdrawal treaty with the UK on Sunday, a document Theresa May touted as the “only possible deal” for an orderly Brexit from March 29, 2019. But by all accounts, that was the easy part. Now what?

Sunday’s agreement, sealed after 18 months of negotiations between Brussels and London, aims to conclude the UK’s 45-year membership in the European bloc, smoothing its exit followed by a 21-month transition period, and outlining a vision for what the future trading and security partnership might look like.

Critics of May’s deal – Eurosceptic and Europhile alike – say May’s deal leaves the UK beholden to EU regulations upon which it will have no say. May, for her part, is betting her compatriots understand that “in any negotiation, you do not get everything you want”, as she said Sunday.

‘Meaningful’ vote

But even May’s allies have admitted that the numbers, for now, are just not there. “The arithmetic for the moment is looking challenging, but a lot can change over the next two weeks,” Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt told the BBC on Sunday, pledging, “we’re going to get through this and give people the Brexit they voted for.”

A European source told Agence France-Presse that May herself acknowledged in Brussels that she didn’t yet have the votes to push her plan through Parliament. The PM confided that she would warn rebellious Conservative lawmakers that at least half could lose their seats in the next election if they don’t back her Brexit deal, the source said.

May needs only a simple majority in Parliament to pass the deal, or 320 votes if all lawmakers turn up to vote. The prime minister’s Conservative Party has 314 active MPs, opposition parties 313 and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the party propping up May’s government after a fraught general election last year, has 10.

More than 80 Tory lawmakers have publicly declared their intention to vote against May’s plan.

Opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn has pledged that his Labour Party, which has 255 active MPs, will also vote against her “worst of all worlds” deal. “This is a bad deal for the country. It is the result of a miserable failure of negotiation that leaves us with the worst of all worlds. It gives us less say over our future, and puts jobs and living standards at risk,” Corbyn said in a statement on Sunday. “That is why Labour will oppose this deal in Parliament. We will work with others to block a no-deal outcome, and ensure that Labour’s alternative plan for a sensible deal to bring the country together is on the table.”

The DUP, which fears May’s deal would weaken Northern Ireland’s ties to Great Britain in avoiding the reestablishment of a “hard border” with EU-member Ireland, is due to leave May hanging. “We will vote against it if it’s brought to Parliament,” DUP leader Arlene Foster told the Irish broadcaster RTE. Foster has also said she would “review” her party’s agreement to back May’s government should the deal pass anyway.

May, for her part, has already shown in a flurry of media appearances her determination to appeal directly to public opinion to bring lawmakers onside. She has said the British people just want to get on with it. And, in helping engineer a Brexit that has, at the very least, the benefit of orderliness, she can dangle the spectre of uncertainty if her deal fails as incentive to usher it through.

“We can back this deal, deliver on the vote of the referendum and move on to building a brighter future,” May told the House of Commons on Monday. “Or this house can choose to reject this deal and go back to square one. It would open the door to more division and more uncertainty, with all the risks that will entail.”

A new deal?

Speaking of just wanting to get on with it, Brussels and individual EU leaders have been clear that there is little to be gained from hopes for a new deal. “Those who think that, by rejecting the deal, they would get a better deal, will be disappointed,” European Commission chief Jean-Claude Juncker told reporters in Brussels after Sunday’s extraordinary summit. When asked whether a House of Commons defeat of the pact could put it back on the table, Juncker said, “This is the best deal possible.”

“There is no Plan B,” Dutch PM Mark Rutte said. “If anyone thinks in the UK that by voting No something better would come out of it, they are wrong.”

Irish PM Leo Varadkar said his fellow EU leaders were not speculating on alternatives to the deal agreed Sunday. “We don’t want to give the wrong impression to people, whether they are passionate Remainers or passionate Brexiteers, that there is another agreement that can command the support of the 28 member states. There isn’t,” Varadkar said. “It’s a deal or no deal scenario.”

No deal

May might not yet have the votes on her side, but she has one persuasive element on her side: Fear. The very real possibility that the UK could crash out of the EU overnight on March 29 (no deal means no transition period, either) may sharpen minds and get reluctant moderates on side, either before December’s meaningful vote or beyond it as the clock ticks down to purported catastrophe.

The Economist points out that, well beyond trade troubles, a no-deal Brexit “would see many legal obligations and definitions lapse immediately, potentially putting at risk air travel, electricity interconnections and a raft of financial services, and throwing into doubt the status of EU citizens in Britain and British citizens in the EU.” Inflation would rise and the British pound’s fall would be “unavoidable”, potentially even “vertiginous”, the London-based economic weekly predicts.

For many Remainers, “no deal” is more unpalatable than Brexit itself. “My red line is I don’t want us to crash out without a deal,” Labour MP Caroline Flint told Reuters. “I just think it’s really high-stakes stuff,” said Flint, a former British Minister for Europe and a Remain voter whose northern English constituency backed Brexit.

Unwilling to countenance the notion of no-deal, Labour Brexit specialist Keir Starmer told BBC radio on Monday that Parliament voting down May’s deal should force the prime minister to either re-negotiate a deal or hold a general election.

No Brexit

On Tuesday, the European Court of Justice will hold an urgent one-day hearing over whether Article 50 can be revoked and the UK unilaterally withdraw its decision to leave the EU. If Europe’s highest court concludes that Brexit can be unilaterally withdrawn, it could give succour to proponents of yet another option: That the UK could simply change its mind and remain in the EU after a second referendum. May has consistently ruled out holding a new vote and London fought to stop Tuesday’s hearing on the grounds the question was irrelevant as a result.

But as the deal-or-no-deal scenario comes into bold relief, observers say support is gaining steam for a new vote with at least a dozen Conservative lawmakers and opposition parties increasingly onside.

It is not clear when the Luxembourg court will deliver its ruling, although Cherry is optimistic it will come before the December vote.

And then?

For all of this wrangling and soul-searching – 29 months after the fateful 2016 referendum that touched off Brexit – over the 585-page withdrawal agreement, the pages that actually outline the future of London’s relationship with the EU number only 26. Or, as Corbyn characterised them, “26 pages of waffle”.

Latent tensions over fishing rights and Gibraltar in recent days may be only a taste of what is to come with the future relationship still largely a blank slate left to be filled in. With the lion’s share of work left to be done, Juncker on Sunday said it was “no time for champagne or applause”.

( AFP and REUTERS)