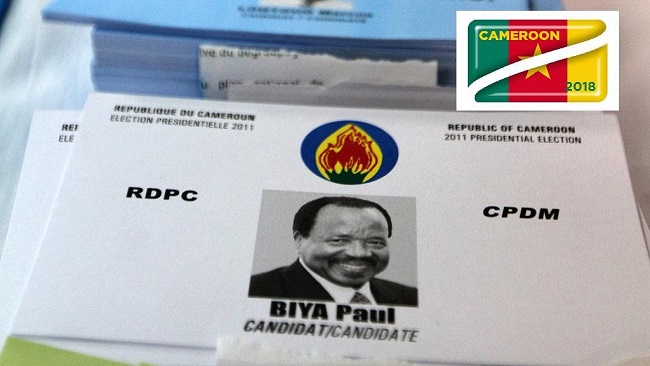

Consortium of CPDM Crime Syndicates: Presidential election still isn’t decided. What happens next?

Cameroon held presidential elections on Sunday, and although an opposition leader has claimed victory, official results have yet to be released. Social media is abuzz with unverified election results, many of which proclaim various opposition leaders as the winners of the elections.

Furthermore, at least two presidential candidates have submitted petitions for partial or total cancellation of the elections to the Constitution Council (within the 72 hours following the close of the poll, as stipulated in the electoral code), reporting electoral irregularities.

But how surprised and concerned should Cameroonians and the international community actually be about what’s happened since Sunday’s election? I asked Cameroonian political science professor Landry Signé to help make sense of what just happened in the nation’s elections. Here’s what you need to know:

Kim Yi Dionne: Analysts expect President Paul Biya (of the ruling CPDM party) to win reelection for his seventh term in office. Still, Cameroon Renaissance Movement party candidate Maurice Kamto proclaimed Monday to have won the election. What should we know about Kamto’s claim?

Landry Signé: First, even some voices from Kamto’s coalition believe Biya to have received more votes than Kamto. Second, in addition to the government, other key opposition parties have condemned Kamto’s proclamation — largely because it is prohibited to self-proclaim results. Finally, we might interpret Kamto’s action as a strategy to gain more international attention, put pressure on the incumbent and gain more legitimacy nationally in order to be perceived as the main voice of the opposition — and the most credible alternative to President Biya.

K.Y.D.: Even setting Kamto’s claim aside, should there be concern about the fact that it’s been five days since the polls closed and the elections board still hasn’t released the results?

L.S.: Electoral law in Cameroon actually gives the institutions in charge of elections up to 15 days to announce the results. Even if this period seems long, it is consistent with previous elections and the rules regulating electoral administration in Cameroon. This period cannot be circumvented except through legal proceedings that would have had to occur before the election.

K.Y.D.: But there have been reports of election irregularities in the elections, right?

L.S.: Yes, observers noted there was unbalanced media coverage of candidates (Biya received three times more coverage than any other presidential candidate), issues with voters having the resources they need to cast their votes, and there were allegations of interference with the electoral process on Election Day. But this is not surprising: Cameroon has a long history of imperfect elections, and it is difficult to change old habits.

To be sure, I’m not saying the instigators of irregularities should get a pass, but the extent of incidents is not significant enough to affect the final outcome. Even without these irregularities, Biya would still win.

K.Y.D.: Why do you think Biya would still win?

L.S.: This is largely explained by a very good but divided opposition. With so many good candidates this year, they have managed to divide the popular vote.

In addition, an area where Biya would have received the least support had very low turnout. Voter turnout in the Anglophone regions was quite low, given a separatist crisis. Separatists in the northwest and southwest regions clashed with state forces in the period leading up to the election and on Election Day, causing many to avoid going out to vote.

Even without a divided opposition and without the separatist crisis, an opposition victory would have still been unlikely. Only 50 percent of eligible Cameroonians registered to vote, and registered voters tend to be pro-CPDM (the ruling party). Furthermore, CPDM’s resources and organizational capabilities are unmatched.

K.Y.D.: I know it’s still early, but does this election leave you resigned or hopeful?

L.S.: I’m actually optimistic about Cameroon’s democratic future. The number of good opposition candidates, the realization of the importance of registering and voting, as well as the current debate on policy options that each candidate has to create a better future for Cameroonians, are giving hope that a transition may be less far off than we think and may possibly happen at the ballot box. There are also emerging voices within CPDM that are advocating for the renewal of the political elite through democratic means. But, if there is really an interest in seriously challenging the CPDM, the opposition will have to come together to mount a successful challenge.

Culled from Washington Post