Southern Cameroonians boycott Cameroun election as violence worsens

Many Cameroonians face being unable to vote in the country’s election on Sunday because of insecurity and fear driven by worsening violence in its anglophone regions.

Paul Biya, the 85-year-old who has ruled Cameroon since 1982, looks set to capitalise on a divided opposition to easily win his fifth election since reluctantly adopting a multiparty system in 1992.

Separatists in the English-speaking regions have announced a boycott of the poll, and many voters there have said they are too scared to go to the polls. At least 400 civilians have been killed in unrest in the past year, and hundreds of thousands have fled their homes.

“Who can vote when our brothers are dying? How can we even vote, when you don’t know how safe it will be?” asked Chimene Ngum, a 23-year-old student in Bamenda, capital of the anglophone Northwest region.

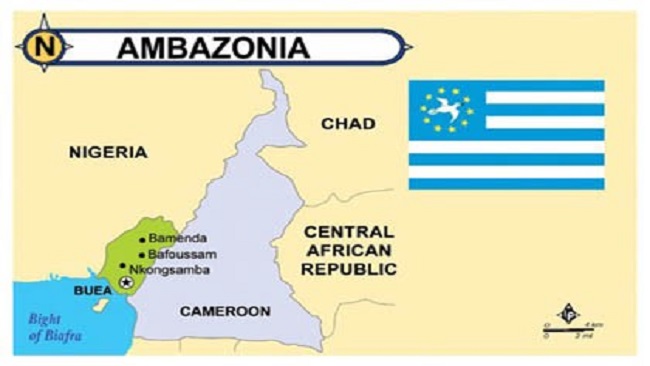

The rebellion that erupted in the country’s two anglophone regions was triggered by the violent repression of a peaceful protest a year ago, after lawyers complained that magistrates were being appointed to their courts despite their poor English. It spread to the regions’ teachers and students, then activists symbolically declared the two anglophone regions the independent republic of Ambazonia.

Biya’s government responded with a wave of arrests and killings.

For years, anglophones have felt deliberately sidelined and neglected, their infrastructure left to crumble. Last year, for instance, Biya’s home region was allocated almost twice the money that the anglophone regions got combined, the public investment budget shows, despite their vital importance to Cameroon’s economy. Much of the country’s oil production is off the coast of the Southwest region, and onshore are its biggest cocoa-growing areas.

Biya was due to visit Buea, the Southwest regional capital, on Wednesday for a rally, but called off his trip at the last minute after the “Amba boys”, as the forces of the Ambazonian separatists are known, issued more threats. It would have been the first trip he has made to the anglophone regions since 2014, in which time he has spent at least 260 days on private trips abroad, many to Geneva.

Teachers who were bussed into a heavily securitised Buea to participate in the ruling party’s rally said they were threatened that there would be consequences if they did not attend. Meanwhile, gunfights broke out between Ambazonian and Cameroonian forces in villages near the city.

It is unclear how many of the 4000 polling stations due to open in the anglophone regions will function on Sunday, though some are determined to cast their ballots.

“I am going to the polls this Sunday, despite the fact that our brothers don’t want us to. They should understand that this is the only way we can get the change we want,” said Judith Mafor, a supporter of the main opposition party. “We have tried with guns and this has taken us to the graves and to the bushes.”

Others said they would not risk voting and described feeling powerless.

“We vote all the time and the outcome remains the same,” said Josephine Ngum, a tailor from Bamenda. “Why do I have to vote again? In a country where real democracy is instituted, when someone’s term of office is over, he steps down for another person to take over. This is not the case with Cameroon.”

Chimene Ngum said she didn’t even have a voter’s card. “Even if I had one, I wouldn’t vote because the results would still be the same. Paul Biya always wins,” she said.

After Robert Mugabe’s fall from power last year, Biya took up the mantle of being Africa’s oldest president, making Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni, 74, and Nigeria’s Muhammadu Buhari, 75, seem young.

Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang, 76, currently holds the title for the longest-serving president in Africa, having ousted his uncle in a military coup in 1979. Biya, who rules his cocoa and oil-producing country essentially by decree, is second.

Culled from The Guardian