Cameroon’s heartbreaking struggles are a relic of British colonialism: Eliza Anyangwe

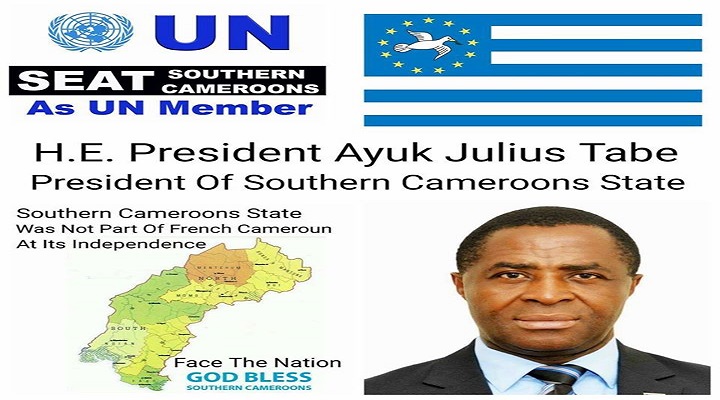

Last Friday, a man named Julius Ayuk Tabe was arrested along with nine others in a hotel in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. Tabe and his companions were reportedly committing no crime, at least not one that has yet been disclosed.

There are inconsistencies in the reporting. Some accounts say 10 people were arrested, while others speak of seven. The BBC’s coverage eschews these details altogether. What remains consistent is that it is alleged that those detained were taken by Nigeria’s intelligence agency, though the Department of State Services denies having them in custody. And so there the story ends. No public outrage – in Nigeria or anywhere else. No international condemnation.

This incident should matter because the violation of anyone’s freedom of association anywhere in the world should be troubling. As has been said many times: “None of us is free until all of us are free.” But in a world where mankind does unspeakable things every day, knowing and caring intimately about each one becomes impossible, so let’s bring this closer to home.

Tabe and his associates are part of a movement seeking independence from the Republic of Cameroon, a fight that would not be necessary if Britain had granted its former colony independence in 1961. What is now referred to as the “anglophone crisis” is in fact yet another hangover of British colonial rule.

After the second world war, Germany’s colonies were redivided among the spoils of the war, with Britain controlling one part of the former German territory of Cameroon and France controlling another. These “trust territories” were supposed to be prepared for independence and majority rule but that would not come for another 15 years. In 1960 France granted its colony independence. For the English-speaking population, in February 1961, Britain however had a different proposition: join Nigeria or the newly formed Republic of Cameroon. The anglophone Cameroonians who opted in that referendum to form a federation with French Cameroon, soon found the terms of that union were void. The promise of equality was never kept, with the English-speaking minority facing widespread discrimination and repression. The ongoing crisis is about decolonisation, not secession.

The ever-present risk of detention is a story I am intimately familiar with. I was born in Cameroon and return often. Going home over the Christmas holidays three years ago, we were constantly reminded to carry our ID cards. Taxi drivers would check as you got into their yellow cabs. “Madame, I don’t want trouble with the gendarme,” one driver told me, after I had got in but could not find my card. Everyone seemed to know someone arrested, or threatened with arrest. These stories, like those that followed the campaign to revive an article in the penal code banning women from wearing short skirts the year before, all end with someone paying a bribe for their freedom.

I am equally familiar with the fight for self-determination in Southern Cameroons. My father is part of the Ambazonia Governing Council, the leadership of the movement seeking independence for the anglophone region they call Ambazonia. I woke up at 3am on Sunday to find him huddled over his phone, talking frantically as he learned of the news of the arrests in Abuja. The question then and now: if we can be arrested in Nigeria, presumably at the behest of the Cameroonian government, are we safe anywhere?

As someone who has benefited from growing up bilingual and who, as many others do, feels “secession fatigue” after the implosion of South Sudan, and the failed attempts at independence in Scotland and Catalonia, I have doubts about what course of action is best, but never about southern Cameroonians’ right to self-determination. The British empire, in its arrogance, did not think this small group of people could effectively self-govern. It was an imperialistic decision that has so far cost hundreds of lives, and seen many others detained in squalid conditions.

Rory Stewart, then the UK minister for Africa, in a statement on 4 October 2017called for all parties to “urgently take action to implement solutions that address the root causes and grievances being raised”. Britain, though it would rather forget it, is one of those parties, and it’s time the government used its influence to get Biya to the discussion table.

Culled from www.theguardian.com