China-backed Kribi port project in Cameroon leaves locals frustrated

Chinese investors want to transform the Cameroonian city of Kribi into to the largest seaport in central Africa. But after initial promises of an economic revival in the area, locals feel left out in the cold.

Kribi’s autonomous port is one of the biggestChinese investment projects anywhere in the world. When it finally opens for business, it will be the largest deepwater port in central Africa.

Some 85 percent of the €1.1 billion ($1.3 billion) budget for the new harbor project is financed by the Export-Import Bank of China, with the rest falling to the government of Cameroon. The state-run China Harbor Engineering Corporation (CHEC) has been overseeing construction.

Natural resources for China

Cameroon’s government is hopeful the new port will stimulate its economy and provide relief for the harbor at Duala, the country’s most populous city, while also providing dock space for larger ships. China, meanwhile, has its eye on nearby iron reserves, which are to be connected to new road and rail infrastructure.

To build the port, the village of Lolabe had to be destroyed. Unfortunately for its 300 inhabitants, land law in Cameroon is a gray zone. When Yasa peoples founded Lolabe in the early 20th century, they did so without property deeds or administrative permission. Very few of the villagers possessed papers proving they own property. They were given a small amount of money in damages and were then forced to immediately leave their homes for a CHEC-constructed housing development.

Rampant corruption

By 2013, only €22 million of the €36 million that Prime Minister Philemon Yang approved for compensation back in 2010 had been paid out. The other €14 million is alleged to have been embezzled by corrupt politicians.

“Villagers were very optimistic when they heard about the harbor project. We hoped it would bring jobs and improve our lives,” said Theodore Ivaha, Lolabe’s vice village chief. “But for the last couple of years we have just gotten more angry because we are not profiting at all.”

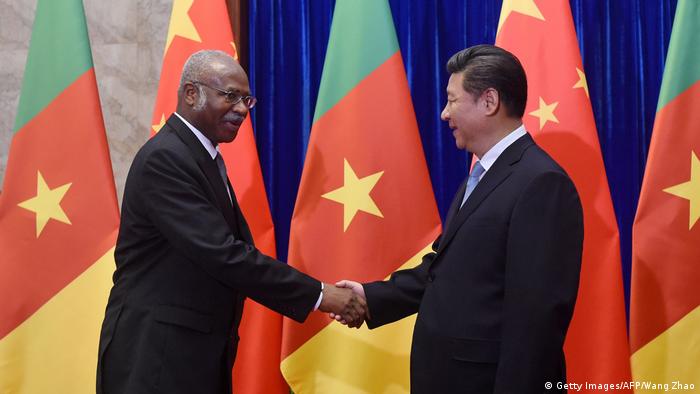

Cameroon Prime Minister Philemon Yang has worked to strengthen ties with Chinese President Xi Jinping

Cameroon Prime Minister Philemon Yang has worked to strengthen ties with Chinese President Xi Jinping

Although construction has created jobs, they are rarely given to locals, instead going to workers from other parts of Cameroon. Most people in the region, and especially those from villages directly neighboring the harbor, simply do not have the qualifications required to fill them.

Villagers waited in vain for the head of CHEC to visit them in an effort to fill positions — something that is regular practice among French companies operating in the country. But it didn’t happen. Job openings were publicly listed and quickly filled. Many of those Cameroonian workers who relocated to the area are accused by locals of having “stolen” their jobs.

Cultural and physical divide

Cameroonian laborers on the building site have complained about working conditions, while Chinese supervisors have derided the locals’ poor work ethic. Chinese site manager Qiangquang Li likened the endeavor to “looking for gold in the desert.”

Chinese and local workers at the site are often separated by more than just cultural divides. The roughly 300 Chinese workers in Kribi reside in a closed camp at the harbor, with living quarters, offices, a cafeteria and a Chinese cook. They rarely leave, and there is little if any contact with locals. Local products, contrary to all prior hopes, are largely shunned by the Chinese workers.

“The government should actually mediate between residents and foreign companies, informing them of the wishes and needs of the locals, helping foreign organizations and companies to foster development,” said investigative journalist Christophe Bobiokono. “But many governments in Africa simply fail at that task, so companies cannot count on them.”

That leaves it up to locals and CHEC to create an effective communication platform. The first steps have already been taken. Now locals are hoping that tourism might take off when family members come to visit those Cameroonian workers who relocated here from other parts of the country.

Culled from Deutsche Welle