War of words and the battle for Southern Cameroons-Ambazonia

The battle lines of the conflict in this central African country are drawn by language. About 80 per cent of the country speaks French; the rest speaks English. For decades, Francophones and Anglophones lived in relative harmony. But over the past two years, violence spurred by this linguistic split has brought Cameroon to the brink of civil war. Hundreds have died, close to 500,000 have been displaced, and activists have been rounded up and jailed.

Witnesses and victims say the government’s use of force has driven a growing number of moderate Cameroonians to throw their support behind the armed separatists, a shift that threatens to intensify the government crackdown and deepen divisions between French and English speakers in the once-peaceful nation. If this conflict spreads beyond the Anglophone regions, it could destabilise the whole country.

“I don’t want Cameroon anymore,” says Daniel, a civilian who fled to Dschang, a French-speaking city close to the border of one English-speaking region, after government forces attacked his village and shot an old woman dead. He asked for his last name not to be used out of fear of retribution for his comments, as did the other English-speaking Cameroonians in this story. “I want to fight for a new country.”

Human rights groups have also accused separatists of attacking security forces and burning down schools, among other abuses. The African Union has called for dialogue but affirmed its “unwavering commitment to the unity and territorial integrity of Cameroon”.

Commander Candice Tresch, a spokesperson for the US Defence Department, said that the United States has received assurances from the Cameroonian government that US assistance will not be diverted from its intended purpose, which includes fighting Islamist extremists in the north. She says the United States closely monitors “units serving in the northwest and southwest against whom credible allegations of gross violations of human rights have been lodged, to ensure they do not receive additional training or equipment if and when they are transferred to areas dealing with the Boko Haram menace”. “We will consider suspending or reprogramming additional assistance when and as necessary,” she said.

The Cameroonian government denies that it is targeting civilians or burning down Anglophone villages. Issa Tchiroma Bakary, who served as communications minister until January, said that the military is defending civilians from the secessionists and that most Cameroonians living in English-speaking regions “are hostages of the separatists”. Badjeck said the military is burning only secessionist camps, not civilian villages.

Civilians who have fled Anglophone areas and advocates working with them tell a different story. Survivors and advocates say violent government attacks on villages have prompted an exodus from Cameroon’s two English-speaking regions in the northwest and southwest of the Anglophone region.

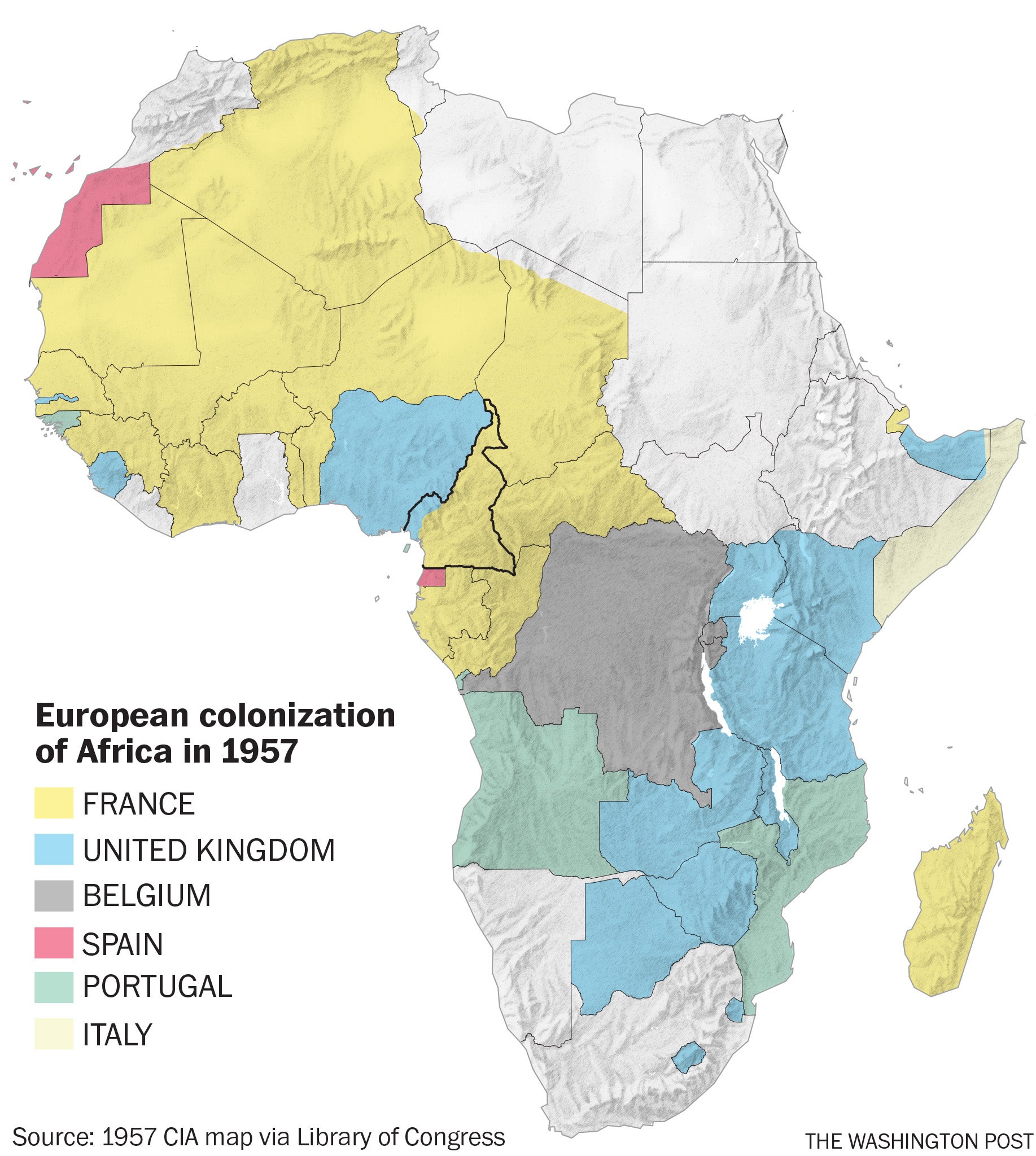

As with other countries in Africa, Cameroon’s modern-day, bilingual identity was shaped by European colonial powers. Even its name, a derivative of the Portuguese camarões or “shrimp”, hints at Europe’s centuries-old control over the country’s identity.

In 1916, France and Britain seized the territory from Germany, and it was later divided between them. Then, in 1960, French-speaking Cameroon won independence and established a new nation: La République du Cameroun. The following year, English speakers in part of the British territory opted to join Cameroon, and a bilingual country was born.

French speakers largely control Cameroon’s government and its elite circles, and some Anglophones have long felt marginalised by the central government. President Paul Biya, a Francophone, has held office since 1982 and was re-elected for another seven-year term in October, after a widely contested election. Many English speakers did not participate in the vote.

Today’s conflict can be traced to late 2016, when English-speaking lawyers and teachers organised peaceful protests, a movement born of frustrations that the government had assigned French-speaking judges and teachers to English-speaking courts and schools. English speakers claimed that officials in Yaounde were essentially forcing the minority Anglophones to assimilate into Francophone legal and educational systems.

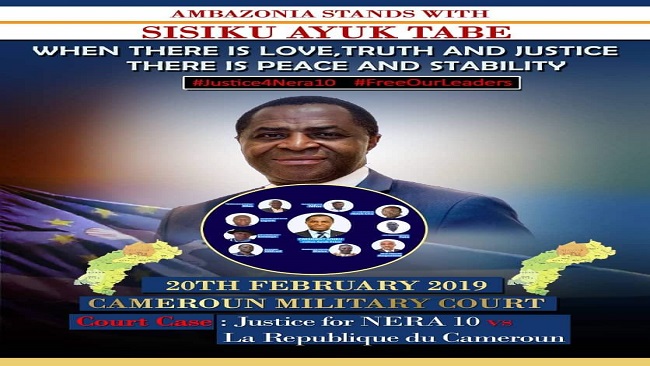

The government claims to have initially agreed to some reforms but also cracked down on the activists, jailing a number of moderate leaders and killing some protesters. The original activists watched from prison as more-extreme voices, those calling for full separation from Cameroon, drowned out what had started as less-aggressive demands.

Those arrests were “the turning point in the struggle”, says Felix Agbor Nkongho, an Anglophone human rights lawyer who helped organise protests and then was jailed. “The movement now had to fall in the hands of people who were more extremist, who were not only clamouring for the rights but wanted independence.”

Fighting escalated in spring 2018. Separatists ramped up their attacks against the military, and the Cameroonian troops retaliated, leaving civilians caught in the crossfire, according to English speakers who fled from the military during that period.

Early on a clear April morning last year, Amkemngu, a local government official from the southwestern village of Azi, woke to the sound of heavy machine-gun fire. Government troops had come to the village, he says, to look for armed separatists. He fled to the top of a hill, clambering through thick brush until he found a clearing. It was from there that he watched as soldiers below opened fire on an elderly woman who was trying to escape.

Hours later, Amkemngu, 64, softly trudged down the hill to dig a hole and bury the woman’s body.

“You can only ask [President] Biya why he is sending his army to come attack his own people,” he says. A member of Cameroon’s ruling party, he even decorated his home with photos of the leader whom his brother, a soldier, died protecting decades earlier.

Now, he’s willing to fight and die for Ambazonia. “There’s no turning back,” he says.

Amkemngu is one of a growing number of English-speaking Cameroonians who, after surviving government attacks on their villages, have grown disillusioned with a unified Cameroon and believe the separatist cause is the only path forward.

He says one of his nephews was shot dead by the military, and two of his sons went missing after troops opened fire on their village in April. In the chaos, soldiers set fire to houses and shops, he says. Losing family members during the military attacks made him lose all faith in the government and pushed him into the arms of the separatists, who he says do not target innocent people.

“Civilians love the way the Amba-boys are behaving with them,” he says, using a local nickname for the secessionists. Aaron, who retired to his village, Oshie, in the northwest, was living quietly, tending to his small cocoa farm for a modest living. Then, in June, soldiers opened fire on his village, and Aaron hid in a hole behind his house.

When the 76-year-old emerged close to dusk, the home he had spent his life savings to build was on fire. Nearby, a relative, a young man with disabilities, had been shot dead. He took one look at his surroundings and fled on foot, eventually reaching the French-speaking port city of Douala. The military crackdown has caused so much damage, he says, that he now sees no future for a unified Cameroon. If he goes back to his village one day, he wants it to be in Ambazonia.

“I don’t want to be here,” he says about Douala. “I don’t feel free here.”

Witnesses to government attacks say the military’s aggressive approach to the conflict, including indiscriminate violence against civilians, has eroded English speakers’ trust in the government and made them fearful of military intervention.

The soldier who shot her friend was wearing a black vest emblazoned with the letters BIR, she says, the French acronym for the Rapid Intervention Battalion, an elite unit that US troops have trained to fight the Boko Haram extremist group in the country’s far northern region.

Badjeck, the military spokesperson, denied allegations of human rights abuses in these villages, saying the accounts amounted to “propaganda”. In an earlier interview, he acknowledged that there have been cases of human rights abuses but said that they are appropriately investigated and that misbehaviour is “not our code of conduct”.

Many English speakers who fled the military still live in fear that they will be targeted in the French-speaking areas where they sought refuge. In Dschang, Daniel, 40, who fled from Azi in April, is sharing two small rooms with a dozen family members. His house in Azi was burnt, and he ran through the bush with his children, avoiding the military along the way.

“Even now,” he says, “the military is searching for us, the youths.”

© Washington Post